Antifa seeks to overthrow “the privileged” and they assume that this violence and destruction will inflame an uprising that will usher in a pure democracy.

Alexander Hamilton and the Politics of Impatience: Part I

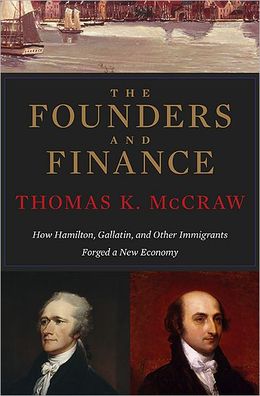

Editor’s note: Occasioned by Thomas McCraw’s The Founders and Finance: How Hamilton, Gallatin, and Other Immigrants Forged a New Economy, this is the first post in a series by Liberty Fund Senior Fellow Hans Eicholz that will explore the contrasting visions for the early American republic in the financial, economic, and foreign policy thinking of Alexander Hamilton and Albert Gallatin. Stay tuned for further developments.

Thomas McCraw has given us a compelling portrait of two major figures at the outset of American financial and economic history in The Founders and Finance. His primary aim is to draw out their similarities—their foreign origins, their experiences in commerce, their capacity to see the big picture of American nationhood—but I was struck more by their striking dissimilarities.

Thomas McCraw has given us a compelling portrait of two major figures at the outset of American financial and economic history in The Founders and Finance. His primary aim is to draw out their similarities—their foreign origins, their experiences in commerce, their capacity to see the big picture of American nationhood—but I was struck more by their striking dissimilarities.

Where Albert Gallatin aspired initially to commercial success; Hamilton very early determined on a political career. Where Gallatin felt somewhat awkward on the political stage, Hamilton thrilled at the prospects of a public career and a public reputation. Where Gallatin learned to roll with the political punches of a diverse and rollicking republic (adapting policies to commercial and political realities), Hamilton formulated a clear, even unitary conception of where America needed to go and what he needed to do to get it there.

While McCraw was obviously drawn to Hamilton, to my own way of thinking, Gallatin comes out marginally better for liberty and the free society. I say, marginally, because Gallatin shared many of the conceptual difficulties of Hamilton respecting markets and finance, but on the whole, he was more patient with his adopted countrymen. Why this is the case has, to my mind, some very profound implications for understanding the divisions within the American political tradition, then and now. Going over these differences could be useful to clarify how one should best conceive the relationship of government to the economy, to public finance and to currency.

For this reason, I want to take my time to consider McCraw’s important work with respect to the notion of patience. To some, this may seem anachronistic. In reality, patience is the frequently used, but little recognized term of Hamilton’s and Gallatin’s contemporaries. Impatience was a charge frequently leveled by Antifederalist against Federalists. It was also a virtue explicitly recognized by leading lights of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Occasionally being the man with a plan is a good thing, but often in matters of politics and economy it is not. Lord Acton warned of the character of great men. Doing something memorable frequently means doing something sufficiently disruptive as will not soon be forgotten. The study of economics began in large measure as a tool for such “great men” to cajole, clip and prune the economy to suit their particular uses—or what frequently amounted to the same thing: the uses of the state.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Adam Smith’s investigations had brought the efficacy and desirability of much of this clipping and pruning into doubt. A synthesis of conservative and enlightenment ideas had, by his time, coalesced around the notion of natural liberty—the view that society, if left alone, could achieve a peaceful and productive stability on its own. Above all such a view counseled, not the virtues of the “do-something’s”, not the virtues that promised the rewards of grand reputations, but the boring, mundane virtue, little praised or sung, of patience. This was the virtue of Old or True Whigs. A young Edmund Burke wrote an entire essay dedicated to this natural society, and Adam Smith anticipated Acton when he wrote in the Theory of Moral Sentiments:

With what impatience does the man of spirit and ambition, who is depressed by his situation, look round for some great opportunity to distinguish himself? No circumstances, which can afford this, appear to him undesirable. He even looks forward with satisfaction to the prospect of foreign war, or civil dissension; and, with secret transport and delight, sees through all the confusion and bloodshed which attend them, the probability of those wished-for occasions presenting themselves, in which he may draw upon himself the attention and admiration of mankind.

Early in McCraw’s narrative we are presented with a startling letter of a very young Hamilton to Ned Stevens:

I’m confident, Ned that my Youth excludes me from any hopes of immediate Preferment nor do I desire it, but mean to prepare the way for futurity. Im no Philosopher you see and may be jusly said to Build Castles in the Air. My Folly makes me ashamed and be youll Conceal it, yet Neddy we have seen such Schemes successful when the Projector is Constant I shall Conclude saying I wish there was a War.[sic] (16)

McCraw presents Hamilton as a man possessed of abundant industry and fortitude, but decidedly not patience. His lowly origin in a Caribbean outpost left him acutely aware of his vulnerabilities, and this gave urgency to his desire for a “military reputation,” to “act a conspicuous part in some enterprise that might perhaps raise my character as a soldier above mediocrity.” That aim was the source of tension with Washington, and McCraw notes that “To understand…this is to grasp the essence of his character.” Once he had obtained his desired opportunity—a daring night assault at Yorktown—Hamilton was anxious to move on, and quickly resigned his commission, grandly renouncing even his compensation. It was, McCraw wrote, typical of his “sometimes impulsive temperament.” (31)

On these points, McCraw is exactly right, but to my mind, the wider implications are not as he would have them. Going through this will require patience, but I think the effort worthwhile. My review will follow in parts. McCraw has done us the great service of putting these two interesting characters side by side. The book is a treasure trove for consideration of the essential points of intersection of America’s political and economic life. It would be best if we take our time to consider each.

To have a sustainable and stable order of freedom requires a great deal of learning over time. The purveyors of emergency invariably turn to political means to resolve and realize particular objects. In doing so, they short circuit the opportunity for the development of the human capital essential to sustain liberty. Such learning can only be accumulated through trial and error. We often fail to appreciate just how much an extended and spontaneous social order is in fact dependent on the internalization of such experiences. None of the Founders were angels. Each had imperfections. Impatience was Hamilton’s and its implications were profound for the course of American political and economic life.