Publius makes persistent appeal to self-interest throughout The Federalist: what does this tell us about human nature?

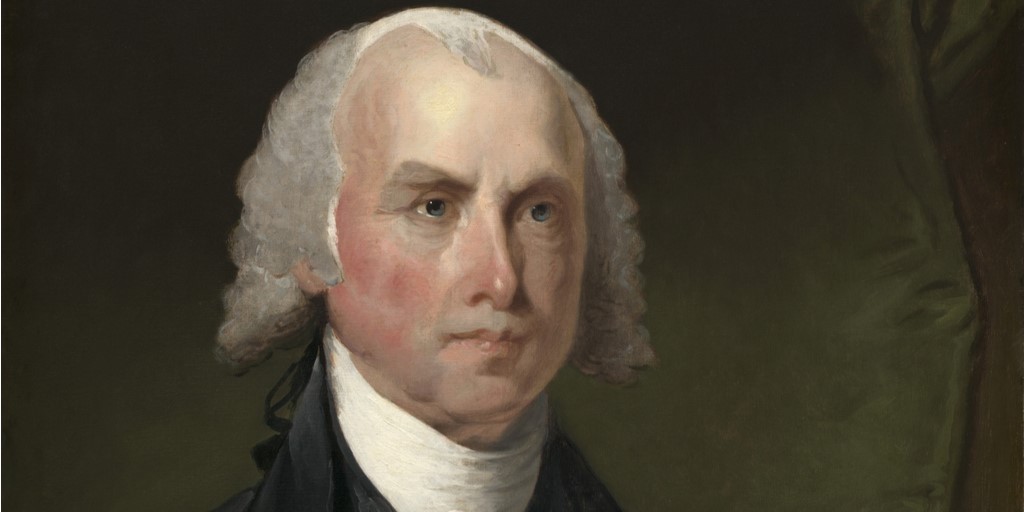

The Limits of James Madison's "Memorial and Remonstrance"

The stridency of the Obama administration’s secularism has led advocates of religious pluralism and the fully-clothed public square back to the Founders’ well to reproduce and rearticulate our vital heritage of religious liberty. Such stridency has been most clearly evidenced by Obama’s lawyers advocating against the rights of a Lutheran church to pick its clergy leadership in the Hosanna-Tabor case and the HHS contraceptive mandate. We could go on here, but these examples will do. Both cases illustrate the desire of the administration to do something that in other policy contexts it wouldn’t dare do: Privatize.

The Obama administration is attempting to do what modern liberalism everywhere announces but has only partially achieved: the reduction of religious liberty to worship and inner-thoughts with no corresponding notion of corporate association or the public ability to live out one’s faith. Without that right, religious liberty becomes a kind of exercise in modern philosophy. So we should recall Descartes’ et al. teaching that you don’t have direct sensory knowledge of extra-mental reality, but what you can access are your ideas about reality, thought thinking thought. Likewise, for Obama, you should have access to religious liberty, but only in and through the thoughts in your mind. Behold, a right that connects with no duties and that has no real measure of influence in the public lives of persons and communities. Some right, some responsibility.

In response some have appealed to James Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments as one of the essential founding-era texts demonstrating the inviolability of religious liberty against the state. Madison’s claim here is absolute and a powerful bulwark against state interference with religious belief; but it is also a problematic defense, one that might go to the heart of our current difficulties. This could seem a strange observation given Madison’s argument that “in matters of Religion, no man’s right is abridged by the institution of Civil Society and that Religion is wholly exempt from its cognizance.” Related to this is Madison’s statement that the person possesses a fundamental duty derived not from government but from nature to “render the Creator such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him. This duty is precedent, both in order of time and in degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society.” Madison has put forth strong language that could easily limit, in theory, the overreaching acts of a monistic state.

The Memorial and Remonstrance exemplifies the modern replacement of the very corporate notion of freedom of the church with freedom of conscience. The concept of freedom of the church is succinctly introduced and explained by John Courtney Murray in We Hold These Truths where he announces that it “served as the limiting principle of the power of government.” Its effect was to provide “a corporate or social armature to the sacred order, within which res sacra homo would be secure in all the freedoms that his sacredness demands.” In short order, “men found their freedom” in their faith which was the Church. Secondly, this freedom provided the “ultimate directive principle” to government by standing between the body politic and the public power, “not only limiting the reach of the power over the people, but also mobilizing the moral consensus of the people and bringing it to bear upon power.”

Paul Rahe recalled this point in his much noted essay “American Catholicism’s Pact with the Devil:”

I mean that, in the course of defending its autonomy against the secular power, the Roman Catholic Church asserted the liberty of other corporate bodies and even, in some measure, the liberty of individuals. To see what I have in mind one need only examine Magna Carta, which begins with King John’s pledge that

the English Church shall be free, and shall have her rights entire, and her liberties inviolate; and we will that it be thus observed; which is apparent from this that the freedom of elections, which is reckoned most important and very essential to the English Church, we, of our pure and unconstrained will, did grant, and did by our charter confirm and did obtain the ratification of the same from our lord, Pope Innocent III, before the quarrel arose between us and our barons: and this we will observe, and our will is that it be observed in good faith by our heirs forever.

Only after making this promise, does the King go on to say, “We have also granted to all freemen of our kingdom, for us and our heirs forever, all the underwritten liberties, to be had and held by them and their heirs, of us and our heirs forever.” It is in this context that he affirms that “no scutage nor aid shall be imposed on our kingdom, unless by common counsel of our kingdom, except for ransoming our person, for making our eldest son a knight, and for once marrying our eldest daughter; and for these there shall not be levied more than a reasonable aid.” It is in this context that he pledges that “the city of London shall have all it ancient liberties and free customs, as well by land as by water; furthermore, we decree and grant that all other cities, boroughs, towns, and ports shall have all their liberties and free customs.” It is in this document that he promises that “no freemen shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or exiled or in any way destroyed, nor will we go upon him nor send upon him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land” and that “to no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay, right or justice.”

To be clear, I’m not arguing for an exact re-imposition of this legal principle that the Church of the Magna Carta insisted on. Perhaps a significant question is if its “armature” that comes from its connectedness to the full reality of the religious needs of the human person as lived in community can so easily be dispensed with as was assumed in modern political thought? Murray articulates that the political edifice of the modern experiment was that the “workings of free political institutions” would reflect and be limited by the “ethical imperatives” of so many spontaneously working consciences. The “immunity” supplied to the “sacred order” was founded in the “freedom of the individual conscience.” This certainly seems to be the fundamental argument invoked by Madison in his Memorial and Remonstrance.

In his book American Compact, Gary Rosen argues that the apparent radical teaching of Madison that government was limited by the citizen’s duty to God as a person, is hedged by both its individualist context and Madison’s need to separate the things we do corporately with the body and the things we do privately with our minds. Madison, Rosen notes, looks to “the privileges enjoyed by individuals. . . . It is highly personal, so it discourages both collective action and deference to religious authority. . . . And it is resolutely other-worldly, so it manifests itself not in ritual observance or faith-inspired works—messy and quasi-political matters that involve our bodies—but in “conviction,” in the “opinions” that depend on our minds.”

If Rosen is accurate that Madison’s document “does not so much trump the social compact” as hew to the notion that religious belief is an experience, not a doctrine, then such subjectivity places sincerity at the forefront and downplays “right-thinking and acting.” Hence the ability to separate conceptually and practically body and soul is possible. Our duty to God comes first in the Memorial and Remonstrance, but it is a weak one, Rosen concludes.

Rosen compares this right with the significance of the body in Madison’s thought. The body is the source of social compact because its desires and needs “were the only legitimate basis for the most authoritative human association” that of political society. These “promptings” held surety unlike the words of the prophets or apostles, which were ambiguous for Madison who denied “the human capacity to know the nature and existence of the commands of—and thus the duties toward—revelation’s God.” Perhaps what is foremost for Madison is to make religion safe for political society.

I come not to argue that we are ill-founded with regard to religious liberty, but to note certain limitations of principles present at our founding. Of course, Madison’s document is only one of many other significant defenses of religious liberty in American history. However, the juxtaposition of the social compact and religious liberty in a robust philosophical fashion by a thinker directly connected to the First Amendment surely moves it to the front of our deliberations on religious liberty.

Perhaps other sources can be combined with Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance to elevate it. If so, we might reconsider the teaching of the freedom of the church in its different contexts to better ground religious liberty. John of Salisbury’s articulation in his legendary work, Policraticus, provides much in this regard. John Inazu’s Liberty’s Refuge: The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly that underscores the corporate nature of religious freedom and the American incorporation of it, quite forgotten by the Court, is also worth reading.