Sect and Power in Syria and Iraq

Important as it is to keep in mind that sectarian socio-religious hate is what drives the vast bulk of the people engaged in today’s Muslim-world war, understanding that war requires taking into account those who provide the contending forces’ military organization. On all sides, this has less to do with religion than with secular considerations, including by highly placed atheists, of how to promote their own power. Let us consider each side’s mixture of sectarian factors and local power politics.

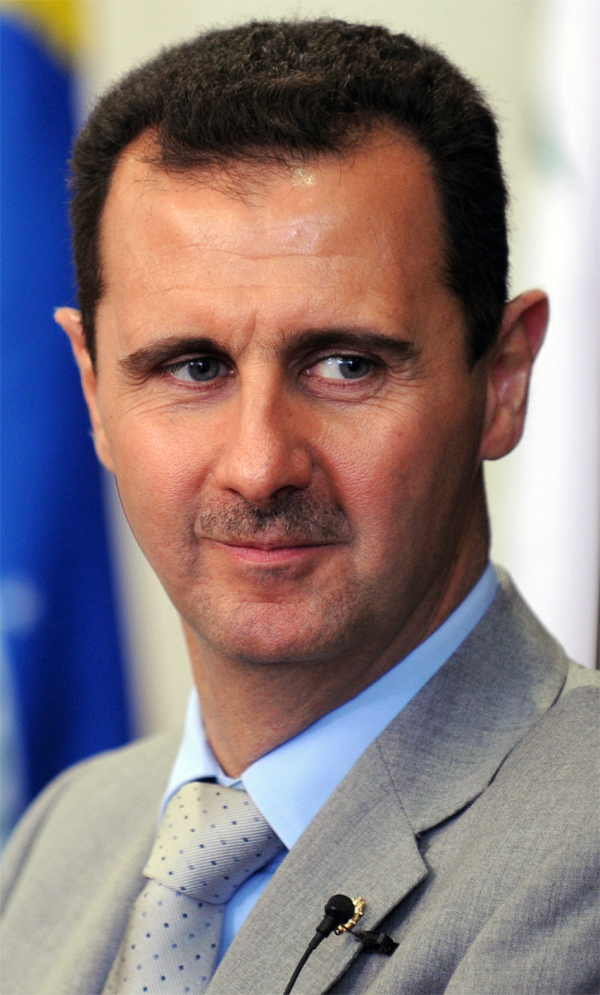

Bashar al-Assad

Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, is an atheist who, like his father, ruled a majority Sunni country although belonging to its Alewite minority. Their rule was based on the very secular Ba’ath party. They kept the Middle East’s best-equipped army, lavishly supplied by the Soviets and then by Russia. But the Assads also kept a special force of Republican Guards, complete with an armored division, composed exclusively of Alewites.

Saddam Hussein, also an atheist, ruled majority-Shia Iraq though he belonged to the country’s Sunni minority. Like the Assads, Saddam ruled through the very secular Ba’ath party. Like them, in addition to a large conventional army made up of the country’s majority population he kept a Republican Guard, better armed, better paid, and manned by his own Sunni sect.

In short, Syria’s and Iraq’s Ba’athist regimes secured secular power through sectarian means. When their power broke, both countries were revealed as artificial empires composed of sects, each of which has sought and received aid from its co-sectarians to organize itself for war.

Assad’s attempt to help the Sunni rebellion against the U.S. occupation involved hosting an influx of Sunni militants from around the world, organized by the head of Saddam’s party Izzad Ibrahim al Douri. He too built his own especially loyal force, the Naqshabandi Army. Stymied in Iraq, the Sunni militants fostered Sunni militancy in Syria. When the Sunni rebellion broke out in 2011, Syria’s regular army –consisting largely of Sunnis, broke. Assad was reduced to his Republican Guard.

This was not enough, however. The Syrian Sunnis were backed not just by al Douri’s Iraqi-international contingent, but by substantial aid from Turkey as well. Turkey played the same role for the Sunnis against Assad’s Alewites, that Assad’s Syria had played against Iraq’s Shia. And so Iran came to Syria’s rescue. Its special Quds force organized the Alewite militias and meshed their operations with Assad’s Republican Guard and the Lebanese Hizbullah into a force that saved the Damascus-Aleppo area for the regime.

The Sunni forces, well organized and established in north-central Syria, extended their state into ancestral Sunni space in Iraq. The extent of that space depends on what resistance Iraq’s Shia can muster.

What remains of Iraq is Shia. The U.S. invasion had broken Sunni-based Ba’ath power. Inescapably, it alienated the Sunni minority from a country that was theirs only insofar as they ruled it. (The Kurds never considered being part of Iraq any more than they were forced to be.) The U.S. government berated the ensuing Malaki regime for being excessively oriented to the Shia majority. But in fact Malaki had sidelined and alienated the Shia militias. Its US-equipped army, insufficiently motivated, collapsed at first shock.

In 2014, Shia Iraq faces the same question that Assad faced in 2011-12: Who will fight for us, and why? The answer is simple: Shia will fight strictly for Shia sectarian causes. Grand Ayatollah al Sistani, Shia Islam’s highest authority, who had managed to avoid political involvement, nevertheless called his flock to arms to fight the Sunni as a religious duty. The Shia militias have answered. But who is organizing them into an effective force? The same people who organized Syria’s militias and other forces: Iran’s Quds.

Who, then, is doing what to whom, and why?

Assad and al Douri are playing sectarian politics as best they can under circumstances that changed beyond their ability to control, but for the same Ba’athist purposes as ever.

Turkey is supporting the new Sunni state – over and above any personal Sunni prejudices on Prime Minister Erdogan’s part – because its existence diminishes Syria, with which Turkey has its southern, longest border, as well as Iran, with which Turkey has its eastern, least defensible border.

Why is Iran saving Syria and Iraq from the Sunni onslaught? Religious affinity is not the dominant factor: Although Iraq’s Shia are legitimately so, the Iranians despise them as Arabs. Whatever Iran does in Iraq, it does for itself. Syria’s Alewites, though closer to Shia than to Sunni Islam, are so far that many do not consider them Muslim at all. But for Iran, Persian and Shia, the primary foreign policy reality is that it is a racial and religious minority all set about with enemies. The Ayatollahs who succeeded Khomeini are increasingly less religious than secular authorities, whose rhetoric veils realpolitik. They seek buffers.

What is all this to Americans? Gratefully, nothing that is going on in that region today is our business. The U.S. government should make it clear to all involved that, were any of them to make it our business by threatening our peace, we would undertake nation-destroying rather than nation-building.