The economy will go south in a hurry if our policy makers follow the recommendations of American Compass.

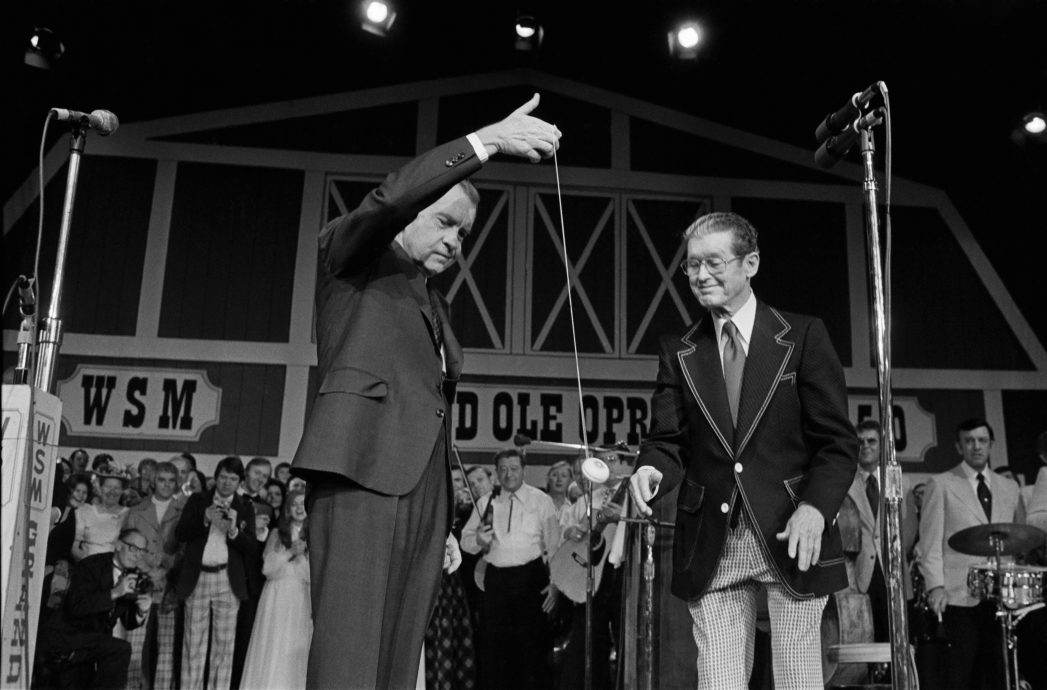

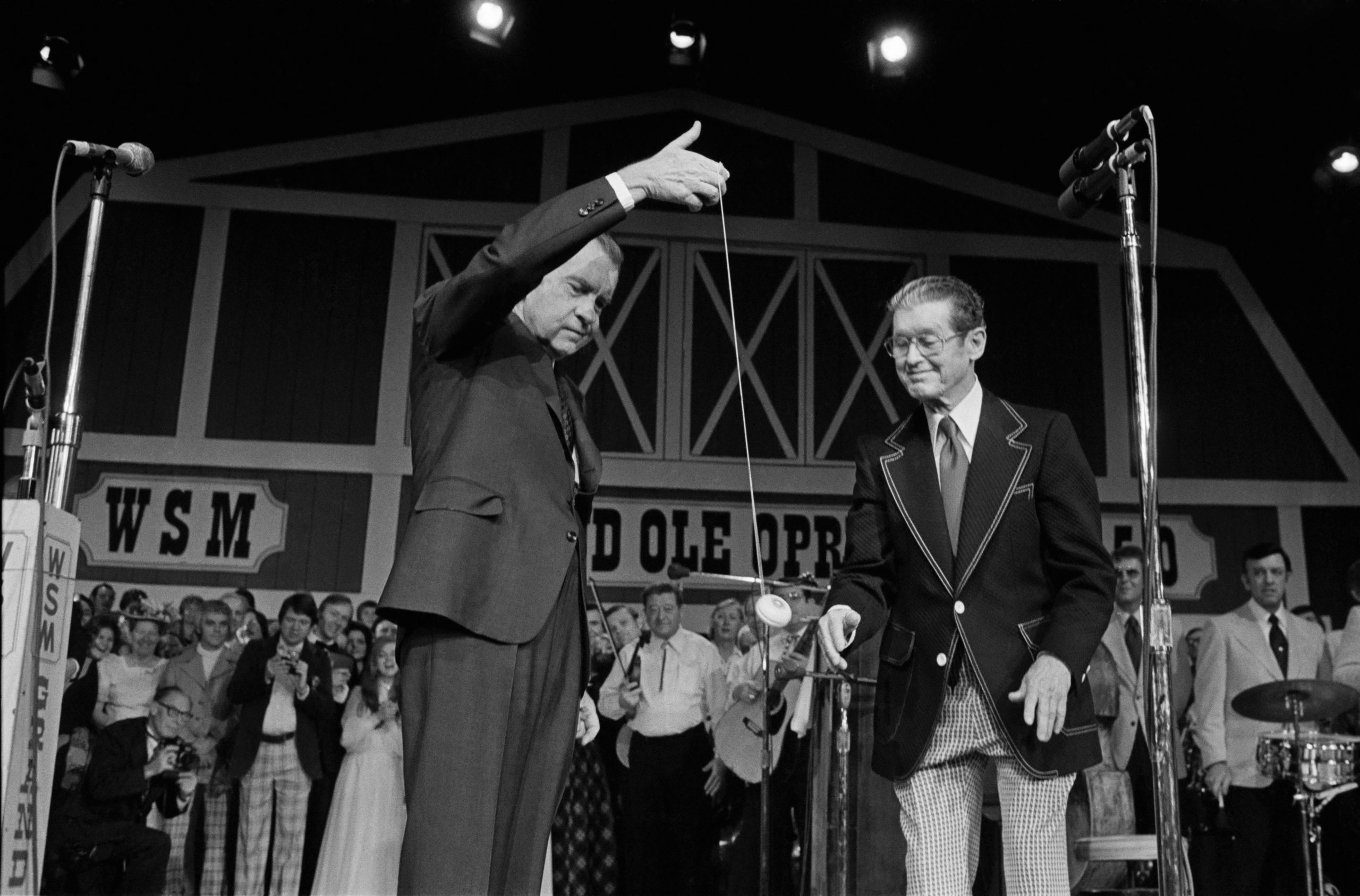

The Guilelessness of Tricky Dick

Richard Nixon opens the new Grand Ole Opry

In Oliver Stone’s laughable Nixon (1996), the director’s penchant for inventive history is exampled by a drunken—and randy—Pat Nixon advising her husband to destroy the tapes. “They’re not about you,” she slurs, “they are you.”

This has been certainly seconded by Nixon’s critics. For 40 years, they have zeroed in on the potty mouth (the biggest surprise for my Republican parents), the anti-Semitism, the enemies list (the work of a “fascist,” according to William F. Buckley), the pay-offs, the disturbing plots against political enemies (for example, slipping LSD to hostile reporter Jack Anderson), to present the image of a paranoid, insecure totalitarian.

Never mind that John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson had surreptitiously taped others. Unlike Richard Nixon, they played to the hidden microphones, putting their best foot—or to be more precise, their best voice—forward. In contrast, Nixon (who had removed Johnson’s bugs from the Oval Office but, ironically enough, installed his own on the advice of that bugger par excellence, J. Edgar Hoover) played himself—perhaps because he believed no one but he would ever hear them.

The release of the final 340 hours of the tapes, transcribed and edited by Douglas Brinkley and Luke A. Nichter, will disappoint the Nixon-haters who undoubtedly smacked their lips in anticipation of more smoking guns, more skullduggery, and more proof of the 37th President’s bizarre character.

This is not to say that there are not moments that provide grist for their mill. In a February 1, 1972 conversation with Billy Graham and Bob Haldeman, Nixon asserts that the Jews control the media, and since said media hates Nixon, he concludes that “most Jews are left-wing . . . They’re way out . . . They’re radical.” Clinton-like, his actions are guided by how to frustrate the “Gotcha” media of his day, and by what plays best in the polls.

That same year, when Alabama Governor George Wallace is shot, Nixon reluctantly provides Secret Service protection to his bête noire, Senator Edward Kennedy. The reason is not humanitarian but to prevent the media from criticizing the administration in case the brother of JFK and RFK—who was at that time, like Wallace, a polarizing presidential candidate—were attacked.

Present too is his well-known obsession with President Kennedy, although it is much more muted here than in other batches of the tapes. He denounces JFK as a liar on Vietnam—on the same plane as LBJ—who increased U.S. involvement in Vietnam despite the South’s not having a stable government. Kennedy’s foreign policy overall he qualifies as a failure because JFK lacked “iron nerves.” LBJ, on the other hand, was a failure because he had no “experience.”

Liberals and the Left have often depicted Nixon as attempting to be presidential without having the talents to actually be the chief executive. They trace his limitations to his insecurities and failures. Their psychologizing at the time held that Nixon was jeopardizing the Constitution because he “didn’t make the Whittier football team.” But whatever insecurities he possessed, his performance as President was not one of them. He here shows himself to be quite sure he’s pursuing a “strong, responsible foreign policy” far superior to that of Kennedy and Johnson, and predicts that subsequent administrations, composed in his words of “weak” Democrats, will wreck it.

Foreign policy predominates in these tapes, and this validates Nixon’s later claim in his memoirs that he was focused more on these matters than on overseeing any “plumbing” operations to stop administration leaks to the press.

The Nixonian “bunker mentality” is only faintly detectable, and is surprising on many levels. He speaks of a threat from “radicals” who want “peace at any price” regarding Vietnam. Their assault, he says, will not end when America’s involvement in Indochina does; their goal is to wreck the country. To me at least he looks rather prescient on that—if less so regarding the political Right. That bunker mentality of his, according to the conventional wisdom, came from irrational fears that the Left was about to foment a coup. What emerges from these transcripts is a remarkable correction of the historical record: Ronald Reagan, then the Governor of California, poses more of a threat to democracy than the antiwar demonstrators, in Nixon’s view. Reagan and his followers, says the President, “will finish the revolution that the Left starts” and overthrow the Constitution once in power.

In fact it is apparent throughout these transcriptions that his fellow Republican Reagan obsesses Nixon as much as JFK does. He finds him a lightweight and yet keeps a nervous eye on him in this period.

The conservative camp was, as we know, a thorn in Nixon’s side. Many conservatives (including Buckley) believed this veteran of the Alger Hiss spy case nonetheless gave away the store to the communists in China and Russia. But a little-known matter emerges in these pages concerning the Russians’ building a nuclear submarine base in Cuba, and this a decade after the Cuban Missile Crisis that gripped the world.

It is January, 1972. The President threatens that, unless the Soviets cease this project he will, like Kennedy, go public and inaugurate what he calls the “Cuban Missile Crisis Part Two.” The Soviets blink, without Nixon’s trading away any advantages as did Kennedy when the latter removed American missiles from Turkey as part of a secret deal with Nikita Khrushchev. (Hence, regarding Cuban policy, Nixon’s self-assessment seems on the mark—he did his predecessor one better.)

He never has any illusions about Leonid Brezhnev, despite the oft-portrayed cuddly relationship that pundits alleged. Peace through strength is the order given to Henry Kissinger on the eve of a Russo-American summit. While not going so far as to instruct his National Security Advisor to peddle the “mad bomber” theory (in which “good cop” Kissinger would tell the Soviets that the “bad cop” commander-in-chief might fly off the handle and empty the nuclear missile silos in their direction), he does instruct Kissinger to tell the Soviets that he is ready to scrap all summits regardless of any negative public opinion polls.

For the Left then and now, Nixon is a rightwing neurotic who sought to overthrow the Constitution. Then, too, conservatives—especially those of a libertarian bent—can find just as much wrong with him. He contemplated, for example, a much more draconian curtailment of Americans’ gun rights than anything the current occupant of the White House has tried. Nixon not only wanted all guns registered but he also wanted to ban handguns. He instituted wage and price controls, not only because the economy as he perceived it was ailing, but as a warning to the “Wall Street boys” to behave. He favored abortion, chillingly enough, for the purpose of population control—a view that one finds occasionally among elite types of the mid-20th century, but is startling to encounter from the humble Quaker boy from Whittier, California.

If, as Oliver Stone’s Pat Nixon asserts, the tapes “are him,” then Nixon emerges as a much more complicated figure than previously thought.