An appeal to what are self-consciously seen as mere symbols and myths won't help us escape our postmodern condition.

Remembrance of Things Past

How persistent is memory, politically speaking? Machiavelli argued that “the memory of ancient liberty,” possessed by republican peoples, is tenacious, presenting an obstacle for a ruler bent on tyrannizing those long used to self-government. In chapter 5 of The Prince, he counseled harsh measures like wiping out the entire population as the only sure mode to exterminate the remembrance of things past. Instead of Carthage-scale eradication, the society in The Giver has found a new mode—seemingly kinder and gentler—by which to neutralize memory, thereby creating a pliant citizenry.

The Giver is not political philosophy, but it’s the next best thing: science fiction. More specifically, The Giver is a 1993 “young adult” dystopian novel by Lois Lowry, just brought out in a film version so now you can expect to find the story (and its sequels) shelved under the bookseller’s rubric, “Now-a-Major-Motion-Picture Books,” along with The Hunger Games, Divergent, The Lord of the Rings, The Great Gatsby, and Romeo and Juliet. I don’t know about the first two in that list (not having any plans to see or read them), but the print versions of the last three are superior to the cinematic ones. So too with The Giver, which is not to say that the movie doesn’t have its good points.

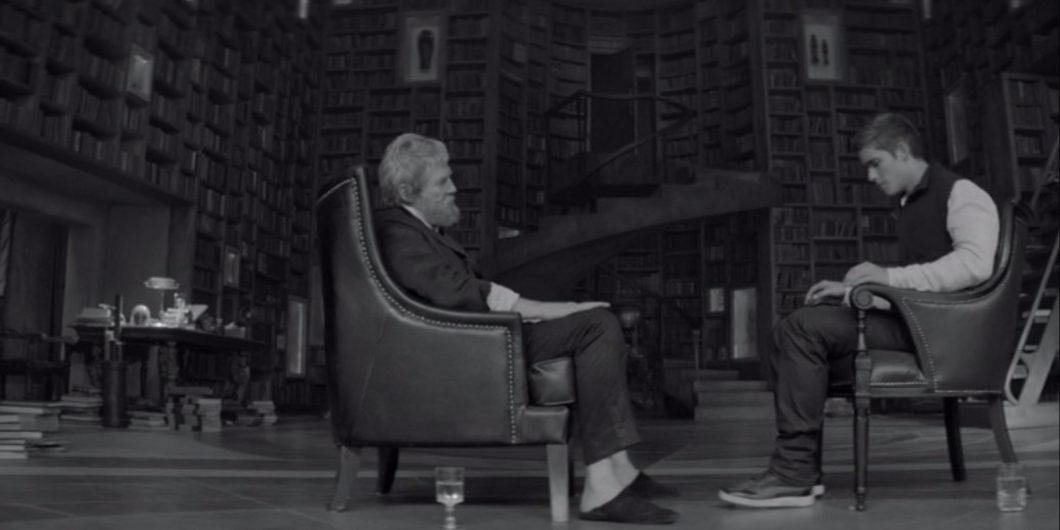

The central conceit in The Giver is that the memory of the past—the past before the societal transformation to “Sameness”—is possessed by a solitary individual. This “Receiver of Memory” is greatly honored but also radically isolated by the tremendous burden that he bears. He alone lives deeply, with joy and pain derived from the books that surround him in his library and the memories that have been entrusted to him by the previous Receiver. Everyone else lives the diminished life of Nietzsche’s “last man,” memorably described in Thus Spoke Zarathustra:

“What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is a star?” thus asks the last man, and he blinks.

The earth has become small, and on it hops the last man, who makes everything small. His race is as ineradicable as the flea-beetle; the last man lives longest.

. . . .

A little poison now and then: that makes for agreeable dreams. And much poison in the end, for an agreeable death.

No shepherd and one herd! Everybody wants the same: whoever feels different goes voluntarily into a madhouse.

. . . .

“We have invented happiness,” say the last men, and they blink.

Like Nietzsche’s last men, the residents of the Community mistake this shrunken existence for utopia.

The Receiver’s official purpose is to be available to give advice to the Committee of Elders in the unlikely event that something unexpected arises. While it is stated that the people long ago chose “Sameness” for themselves, it seems plausible to posit a forgotten Founder who, understanding the connection between memory and wisdom, made a place, an honored place, for a Socratic philosopher while at the same time insulating the Community from the disruptive potential of his presence. The Receiver does not frequent the marketplace or the gymnasium as Socrates did.

Both novel and movie tell the story of Jonas, the youngster selected to be the new Receiver of Memory. The education of the next philosopher-in-residence is a dangerous moment for the Community, for a true education will reveal the artificial character of the political horizon. It’s worth remembering that Plato makes this point about all political horizons, not just the ones we regard as dystopic. The education also requires the suspension of the normal code of behavior. Jonas is issued explicit instructions: “From this moment you are exempted from rules governing rudeness. You may ask any question of any citizen.” In order to navigate the gap between his growing knowledge and the ignorance of his fellow citizens, he is even told “You may lie”—an instruction that rocks him to the core since it contravenes his entire upbringing.

While the novel focuses almost exclusively on this teacher-student relationship, the movie considerably enlarges Jonas’s connections to two friends, Asher and Fiona, and plays up the love-interest angle. It’s hard to object to friendship as a theme, nonetheless, some of the intricacy of the Giver-Receiver relation is lost in the attempt to make The Giver more like other action-oriented movie fare. While the novel has more interiority, the movie does capture the wonder of Jonas’s discovery of color as he breaks free of the imposed huelessness. Whereas Lois Lowry focuses on the primary colors of nature—the red of the (doubtless symbolic) apple—the movie adds the rainbow of anthropological diversity, with its vibrant clips of cultures past. I was reminded of Churchill’s essay “Painting as a Pastime” where he brilliantly describes his new relation to color resulting from his “joy ride in a paint-box.”

Through the Giver’s physical transmission of the world’s store of color, music, and beauty, as well as pain, hunger, and war, Jonas learns the fundamentals of human existence. He is introduced to the forgotten world of “being”—a word that figures significantly in the novel. Because there can be only one holder of memory, each bit of memory conveyed is thenceforth lost to the Giver. The transmission of civilization is presented as an act of loving sacrifice. I suspect this explains why, despite being surrounded by books, the Giver and Jonas are not shown, either in the novel or the movie, actually reading books or discussing their contents. The wisdom on the printed page is fully shareable without loss or separation; it affords an alternative, non-tragic route to enlightenment. The suggestion seems to be that Jonas will only be able to read books meaningfully after he has had a fuller humanity restored to him through the costly gifts he receives. The Giver might be fruitfully compared to another childhood classic, Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree, another tale of unstinting devotion.

More than most genres, science fiction depends on “the willing suspension of disbelief,” since the “science” is always a stretch. It is a concession one grants the author/filmmaker for the sake of the thought experiment being conducted. In this instance, the advent of “Sameness” was linked to the technological achievement of “Climate Control”—control so complete that the denizens have no experience of rain or snow or even sunshine. The Community occupies a plateau with a uniform sky and some plant life, but no acquaintance with animals other than the plushy “comfort objects” for small children. The animal in man is effectively suppressed. Upon the first appearance of adolescent “stirrings,” pharmacology ensures that such dangerous passions are kept well in control. Without sex, children are engineered by geneticists, gestated by low-ranking “birthmothers,” then placed with couples who have applied for childrearing duties, up to the allowed limit of two children, one boy, one girl. Work assignments are made rather like in Plato’s Republic upon the principle of one man/one art. Through careful observation, the Elders discern who is fitted to be a Fish Hatchery Attendant, who a Caretaker of the Old. Thus, we see that the principle of “Sameness” is compatible with the minor differences that allow for a functional division of labor. We see, too, how science and philosophy alike can be put in the service of a completely static society.

There is no religion, but life is highly ritualized. Ceremonies mark every step in their rule-bound lives. Instead of grace before the evening meal, the domestic unit has a moment of “Feelings” in which the day’s minor worries and disappointments are expressed. By this mechanism, individual feelings are resolved in ways that make them conformable to the collective. As Jonas becomes aware of wider amplitudes of passion, he realizes that despite the official insistence on “precision of language” (with vague terms like “love” being considered “inappropriate”), the words commonly used are not, in fact, accurate. When his younger sister says she felt angry, Jonas realizes that “shallow impatience and exasperation . . . was all Lily had felt. He knew that with certainty because now he knew what anger was. Now he had, in the memories, experienced injustice and cruelty, and he had reacted with rage that welled up so passionately inside him that the thought of discussing it calmly at the evening meal was unthinkable.”

An important part of orderliness is departing this world in accord with the needs of the Community. The practice of euthanasia is essential—the weak of all ages are subject to “release” and there is, of course, a lovely ceremony beforehand. Jonas’s discovery of the truth of what is happening (and its looming application to the “newchild” Gabriel) triggers his regime-shattering rebellion. Like all serious exposés of totalitarianism, The Giver examines the centrality and pervasiveness of the Lie. Jonas learns that the cheerful, kind man whom he calls “father” and who works in the Nurturing Center is the one who decides upon and conducts the executions of infants, singing out “bye-bye little guy” as he shoves the carton containing a murdered child down the garbage shoot.

While often assigned by middle school teachers, The Giver is also one of the books most frequently objected to by parents (these lists of challenged books don’t mean all that much, since any book assigned regularly will trigger some complaints). Most of the concern is about the depiction of infanticide in the novel, especially whether it is “age-appropriate.” In deference to that concern, the moviemakers deleted the “bye-bye little guy” line, but still managed to capture the bland horror of the scene.

Together, the Giver and Jonas contrive a plan for Jonas to escape beyond the borders of the Community, thus breaking the quarantining of memory, allowing it to flood back into the whole population, so that they will once again understand the meaning of their actions. Thus, in the end, Jonas becomes the Giver. Like the mythological Pandora (whose name means “all-gifted” or “all-giving”), Jonas releases the swarm of memories, the bad with the good. The elder Giver remains behind to help the newly freed Community cope with the fallout, and presumably the political re-founding.

Interestingly, all the male names in the novel are Biblical: Jonas (or Jonah), Gabriel, and Asher. Fittingly, “Jonas” has opposed meanings: dove and also destroyer. Jonas is provoked to destroy the Community (and to save the angelic messenger Gabriel) when he learns that the peace it promotes is the peace of the grave. The Giver is a rather unusual tale of adolescent rebellion since Jonas’s aim is the remarkably conservative one of restoring the possibility of true family. I don’t mean to overlook the emphasis on restoring freedom of choice to the citizens. That freedom was abandoned because, as the Chief Elder mordantly says, “when people have the freedom to choose, they choose wrong.” It’s just that the direction of Jonas’s choice, one the audience is meant to confirm, is so clearly pointed backwards, toward home.

Jonas learns from the Giver’s most treasured memory what family love once felt like—the picture is a Christmas scene, with multiple generations gathered around a hearth. When the experience is passed on to him, Jonas comments on how different current practice is: once children are grown, the parents have no further connection to them; former parents join the ranks of Childless Adults and eventually move to the House of the Old to be cared for by attendants and never seen again. Jonas is not familiar with the term “grandparents” and he is awestruck by the idea of “parents-of-the-parents-of-the-parents-of-the-parents.” While the more youth-centric movie doesn’t attempt to show this fractured isolation of the generations, it does visually convey the difference between the antiseptic and identical “dwellings” of the Community and a home. Moreover, quite subtly, the movie catches the Christian inspiration with its final shot of the gingerbread house, decorated with lights, and the strains of “Holy Night” faintly heard as Jonas and Gabriel sled through the snow. Pretty daring for Hollywood! No wonder it took Jeff Bridges—who acquired the movie rights with the intention of casting his father, Lloyd Bridges, as the Giver—20 years to bring it to the big screen, by which point he himself had become the Giver.