How to be a Conservative

Editor’s Note: This podcast was originally posted on October 13, 2014.

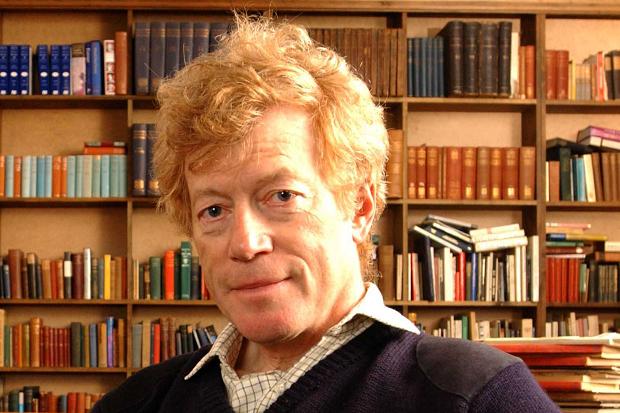

This conversation with Roger Scruton engages his defense of the conservative disposition. Scruton’s just-released book, How to be a Conservative, might be said to take on the challenge Friedrich Hayek issued in his famous essay “Why I Am Not a Conservative.” There, you will recall, Hayek argued that conservatism does not offer a program, or any substantive content that would affirm a free society. It is always in prudential retreat. This conversation explores Scruton’s Burkean-informed notion that tradition and habit aren’t blind guides, but are teachers and modes of social knowledge by which the perennial problem of social coordination is solved. Here begins the basis of Scruton’s elemental defense of the free society and how common law, tradition, associations, religion, and the boring nation-state are integral to its existence.

We begin with the law that governs the contractual relationships of people, a law not shaped by the legislature, but by social and economic interactions. We can say, Scruton observes, that this law is the people’s common law, one that guarantees their property and associations. Centralization is impatient with this private ordering and attempts to upend it with efficient legislation.

While European elites look to the transnational governance of the European Union as the condition of peace and prosperity, Scruton puts before us the nation-state and its borders as the first order of democracy and political accountability. Scruton notes that limited government is about being relational in a particular spot, ring-fenced by borders, and that allows a common life to develop and evolve. Rulers and ruled can hold one another accountable because the terms of government have emerged from the people of this defined group with their particular history, myths, and shared commitments. Such forms of social, moral, and political capital are eroded, Scruton argues, by a boundless and unaccountable European Union, for whom the principle of subsidiarity is, paradoxically, only the powers that Brussels decides to let member states retain rather than a bottom up conception of government and order.

In this regard, we also discuss the “to hell with us” mentality that is multiculturalism. Scruton notes that it’s cold comfort that major leaders are belatedly coming to terms with its wreckage. Multiculturalism’s existence in the government education system, laws limiting speech, and the soft tyranny of political correctness have ensured its ability to redefine life in his native United Kingdom and throughout much of Europe.

Finally, this conversation explores Scruton’s argument that a free market depends not only on an Austrian understanding of the need for local knowledge but on traditions that encircle goods, practices, relationships, excepting these from the market itself. In short, Scruton argues, an enduring free market will have the sense to recognize its limitations. There really can’t be markets in everything.

I look forward to your thoughts on this podcast.