The key conflict these days is between “originalism” and deference to legislatures.

The Predictably Partisan Kennedy Court

According to our Constitution, the President nominates, and with the consent of the Senate appoints, the judges of the Supreme Court. In only 12 of the last 30 years has a single party controlled the presidency and the Senate; therefore, only during those years has there been (largely) uni-partisan control over the selection of new members of the Supreme Court.

All nine of our justices were appointed during the last three decades. Seven, however, were chosen during those more uni-partisan years. Four were appointed under Democratic dominance: Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan. Three were appointed under Republican dominance: Justices Scalia and Alito, and Chief Justice Roberts.

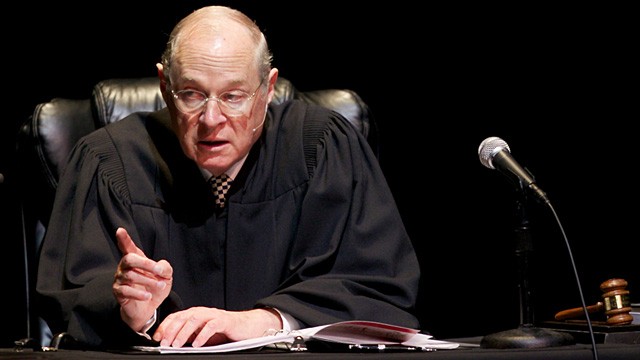

The other two, Justices Thomas and Kennedy, were chosen by a Republican President and confirmed by a Democratic-controlled Senate. In Justice Thomas’s case, his 52 to 48 confirmation vote was nearly uni-partisan—and bitterly so: a handful of conservative Democrats, including future Republican Richard Shelby of Alabama, joined nearly all Republicans in (barely) consenting to Thomas’s appointment. Justice Kennedy, in contrast, was nominated by President Reagan but then unanimously endorsed by the Democratic majority in the Senate. In this respect, his appointment was peculiarly and distinctively bipartisan.

Despite this sharp partisan duality, the justices’ backgrounds reflect a remarkable degree of uniformity. All except for Roberts and Thomas, educated in rural Indiana and Georgia, respectively, were raised in deep-blue urban America, with four born and raised in New York City (Scalia, Ginsburg, Sotomayor, and Kagan), one just outside Philadelphia (Alito), one in Sacramento (Kennedy), and one in nearby San Francisco (Breyer). All went to law school at Yale or Harvard (three at the former and six at the latter).[1] And all save Kennedy spent most of their adulthoods working in the Boston-Washington corridor of power, working for the federal government and/or Ivy League law schools.

Given this geographical, educational, and employment near-homogeneity, coupled with the binary partisanship attending their appointments, it might seem predictable that these justices would fall reliably into two cohesive partisan camps, with the Republican justices voting together as conservatives, the Democratic justices voting together as Progressives, and the bipartisan Justice Kennedy serving as the centrist, swing judge.

According to conventional opinion, our nine justices do not surprise. In deciding constitutional cases, at least, the current Court seems a reliably partisan, 4 to 1 to 4 tribunal, with Justice Kennedy wielding the critical deciding vote.

But in a new book, Uncertain Justice: The Roberts Court and the Constitution, Harvard Professor Laurence Tribe and Joshua Matz (his former student) challenge this common view. They reject reliance on any simplistic “strong left/right split” as an explanatory model. Instead, the authors contend that “the justices are moved by a dizzying array of considerations”—hence the adjective of the book’s title: “Uncertain.”

To support their uncertainty thesis, Tribe and Matz provide, over 300 pages, an extensive survey of the leading constitutional decisions of the Roberts Court from 2005 to the present. Their review is thorough and clear, providing a helpful introduction to the layman and a useful refresher for the expert. It is, however, highly sectarian. It is this partisanship that supplies the noun in the book’s title: “Justice.”

The authors are Progressives and not shy about it. For each case under discussion, they typically give the Progressive voice the last word (if not also the first). This can be seen in the very terms they use to refer to cases. Most notable in this regard is their effort to rename what we might call the Affordable Care Act case, NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), the “Healthcare Case.” This neologism suggests that the Court majority barely upheld “healthcare” while the four dissenters were indifferent if not hostile to Americans’ health.

Tribe and Matz plainly treat Progressive victories more favorably than conservative ones. The 5 to 4 Progressive wins in matters like same-sex marriage (which the authors identify as “marriage equality”) are characterized as fair, in both senses of the term—just and beautiful, and redolent of the “unfolding of history.” On the other hand, the 5 to 4 decisions supporting federalism, the right to bear arms, or the validity of some antiabortion laws, are sins against History: anomalous, contrary to post-1937 Progressive precedents, and somewhat scary. In their words, “fraught with uncertainty,” “new and momentous,” or a “specter haunting the regulatory state.”

The authors reiterate several times the violent novelty of the 5 to 4 decisions in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) and McDonald v. Chicago (2010). The Court “broke new ground” and “forged” or “create[d] a new blockbuster constitutional right.” Yet they reassure readers—in the book’s final sentence—that despite these setbacks “the moral arc of history [is] a long arc that bends toward justice.”

In one interesting trans-partisan note, however, Tribe and Matz draw a connection between two federal spending practices that the Court’s camps often treat quite differently: the conditions for receipt of federal dollars placed on private individuals and institutions, as compared to those placed on the state governments. Their chapter entitled “Rights for Sale: Discounting the Constitution” indicates that Washington’s conditions on the states (for example, the Medicare condition invalidated in the ACA Case) are potentially coercive just as are the ideological conditions imposed on individuals and institutions (for example, the Solomon Amendment upheld in the 2006 case of Rumsfeld v. FAIR). In both cases, the authors suggest, Washington’s conditions are problematic if not unconstitutional.

But the chief defect of the book is that Tribe and Matz’s own survey seems to disprove their uncertainty thesis. The cases do not present a “dizzying array of considerations” or any impenetrable complexity. Rather, the old, reliable Kennedy Court reappears in case after case after case.

By my count, the book treats 34 constitutional decisions. Of these, a clear majority (18 of them) were decided by a 5 to 4 vote, with Justice Kennedy providing the winning vote to either the reliable conservative block or, less frequently, the reliable Progressive block. In eight of these decisions, Kennedy took the starring role by authoring either the majority opinion—for example, United States v. Windsor (2013), which invalidated the Defense of Marriage Act—or the decisive one-man concurrence. An example of the latter is the 2007 case of Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, which invalidated a racially discriminatory integration program.

Moreover, Justice Kennedy seems to relish his role, for he often acts, it seems, to preserve and extend his power as the de facto chief justice. When authoring a majority, or decisive concurring, opinion, he frequently fashions a rule that seems designed to invite further litigation before his tribunal—the Kennedy Court. He rejects bright-line rules that would avoid litigation, in favor of middling opinions that prompt new policies and attendant constitutional challenges.

To cite a few prominent examples:

His vague “undue burden” test set forth in the 1992 case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey (applied in the 2007 case of Gonzalez v. Carhart, which was decided by a vote of 5 to 4) encouraged both antiabortion legislation and judicial challenges to such laws.

His Windsor opinion, with its odd mix of federalism and substantive due process, plainly invited further litigation as to whether the Constitution compelled the states, as well as the national government, to extend the status and privileges of marriage to same-sex couples.

And in his majority opinion in Fisher v. University of Texas (2013) and concurrence in Parents Involved v. Seattle School District 1, Justice Kennedy rejected any blanket rule, whether the conservatives’ color-blind red light, or the Progressives’ pro-diversity green light, and instead invited pro-diversity public schools to establish keenly color-sighted policies, and perhaps even racial preferences, but with the caveat that such policies would be subject to strict supervision and veto by the Supreme Court, where he has become primus inter pares.

Of the other 15 cases treated in the book, most deviated only somewhat from the 4 to 1 to 4 pattern. Five of the 15 involved claims so outside the judicial mainstream that a consensus of the justices overwhelmed Justice Kennedy’s centrality—for the justices were unanimous (or one vote shy of unanimity) in finding governmental action constitutional or unconstitutional. These included two involving the Fourth Amendment (both unanimous), two arising under the Free Speech Clause (one unanimous, and one 8 to 1 decision), and one affirmative action case—the Court’s 7 to 1 decision in Fisher.

By my reading, seven of the 15 cases revealed some, but only limited flexibility in the voting blocks. All these fell under two categories: federalism or free speech. In four federalism decisions, two of the seemingly more moderate conservatives (Roberts and Alito, in three cases) or Progressives (Kagan and Breyer, in one case) joined Justice Kennedy on the other side. And in three free-speech cases, a lone stray Progressive (Stevens and Sotomayor) or conservative (Roberts) tagged along with Kennedy to provide a sixth vote to the other side.

In my estimate, only the three remaining cases provided occasions for the reciprocal intermingling of the two camps. These confused rather than modified the usual 4 to Kennedy to 4 pattern. One case involved freedom of speech and children (California’s ban on sale of violent video games to minors, struck down in the 2011 case of Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Ass’n), and two involved warrantless searches under the Fourth Amendment: drug-sniffing dogs (in the 2013 case of Florida v. Jardines) and DNA-retrieval from the mouths of arrestees (in Maryland v. King, which was also decided in 2013).

In truth, these three cases, and the other 12 exceptions to the 4 to 1 to 4 pattern, largely prove the rule, for contemporary political realities largely explain all these seeming anomalies. As indicated above, virtually all the “deviant” cases have involved three areas of constitutional law: criminal procedure, free speech, or federalism, and none of these topics has occasioned any sharp recent disagreements among Americans in the two major political parties. Since the 1930s, neither Democrats nor Republicans have been particularly interested in federalism. And since the 1980s, both parties have generally been tough on crime and consequently impatient with the niceties of criminal procedure (but with some bipartisan reservations emerging in the past decade). Moreover, both parties modestly endorse free speech, for neither adopts free-speech absolutism, as both parties generally endorse, inter alia, strong exceptions when children are involved.

Interpretive partisanship, rather than political partisanship, may be at work here. Interpretive partisanship explains much of the departure from the 4 to 1 to 4 pattern, especially in the criminal procedure and free speech contexts that have produced the occasional, unusual line-ups and unanimous decisions. In both these areas, the Constitution includes broad, ambiguous language—for example, “freedom of speech,” “unreasonable searches”—favoring individual rights against the government. These naked textual facts frequently occasion a rapprochement, if not convergence, between the more rigid originalist-textualism of conservative jurists and the flexible civil libertarianism of the Progressives.

A close examination of Tribe and Matz confirms the conventional wisdom. With respect to constitutional law, the current Roberts Court is indeed the 4 to 1 to 4 Kennedy Court. In a similar way, the Hughes Court of the mid-1930s was, in fact, a 4 to 1 to 4 panel with Justice Owen Roberts the man in the middle. The historical parallel suggests that the medium-term future of constitutional jurisprudence will largely depend on at least three factors:

1) the political issues that will define the major parties;

2) the party that may be able to replace Justice Kennedy and the other three justices born, coincidentally, under the old Roberts Court (Ginsburg, Scalia, and Breyer); and

3) the degree to which the polity continues to acquiesce in the Court’s attempted resolutions of these issues.

Therefore the 2016 election may prove to be as momentous as the 1936 election in determining the future twists, turns, bends, and perhaps arcs, of our Constitution’s history.

[1] Justice Ginsburg, however, graduated from Columbia Law School after transferring from Harvard.