What's Dignity for the Goose Is Dignity for the Gander

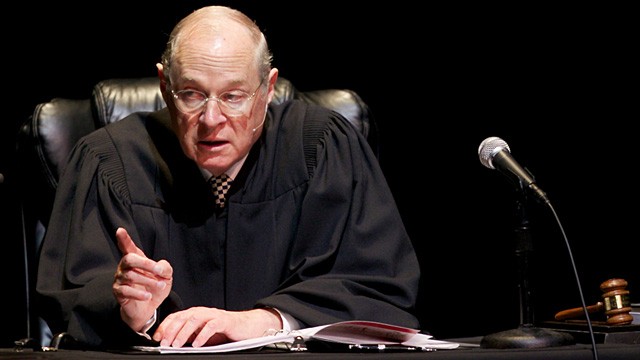

It was in April, during oral arguments in the collection of cases known as Obergefell v. Hodges that Justice Kennedy publicly fretted over the legal outcome that his jurisprudence has, in effect, created. To the surprise of Court-watchers, Kennedy at one point let out that he had “a word on his mind . . . and that word is millennia.”

There it was: an open acknowledgment that tradition, and the social order it has underwritten, do matter—if only so much.

Back in 2003, Kennedy asserted in Lawrence v. Texas that the state’s anti-sodomy law was unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment. The opinion held that we have rights according to general moral criteria derived from the term “liberty” in the amendment’s Due Process Clause. He concluded:

Had those who drew and ratified the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth Amendment or the Fourteenth Amendment known the components of liberty in its manifold possibilities, they might have been more specific. . . . They knew times can blind us to certain truths . . . that laws once thought necessary and proper in fact serve only to oppress. As the Constitution endures, persons in every generation can invoke its principles in their own search for greater freedom.

Rights under the springing Fourteenth Amendment are indefinite, and we don’t know their shape until the Court provides the details. Kennedy’s jurisprudence of liberty is an evolving concept that, strangely, he, as a Supreme Court justice is called to define for the American people. Who among us cannot recite on cue his famous mystery passage in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992)? “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”

You might be forgiven for assuming that the evolutionary nature of Kennedy’s constitutional liberty would be better understood by each successive generation of self-governing American citizens. Each would be more qualified than the last to render such a verdict, as evident in their lives and, consequently, in their voting behavior in local, state, and federal elections. Such an unfolding would, in any event, be more consistent with the competitive and decentralized structure of our Constitution.

Were Kennedy’s surprising millennia misgivings like an exuberant youth who suddenly realizes that he has strayed from true north? If so, what to do? Turn back and find the way home? Or keep going, confident that the initial stirrings that led you to depart from traditional ground will deliver you to the land of dignity, autonomy, and equality?

Most think it likely that Kennedy will follow the latter course. He’s taken it this far; reversing or stalling course is unlikely. And anyway, Kennedy’s oral argument surprise quickly gave way to an even greater fretting about state marriage laws’ conferring dignity on their participants. If state marriage laws are primarily about bestowing dignity on adults, as opposed to the more limited social purpose of connecting fathers and mothers to each other and to their children, then it’s curtains for those defending marriage as an institution grounded in heterosexual complementarity. But we already knew that.

Is there, on the other hand, a principle evident in past Kennedy decisions that affords a compromise, one that would protect religious autonomy from the full sweep of his high constitutional principle of marriage as autonomy and a badge of dignity?

This question becomes even more pressing in light of Solicitor General Donald Verrilli’s response to Justice Alito’s question regarding the holding in Bob Jones University v. United States (1983) that a college was not entitled to tax exempt status if it opposed interracial marriage or interracial dating. Would the same rule apply to a university or a college if it opposed same-sex marriage?, Alito wondered.

As Michael Greve pointed out, Verrilli’s answer wasn’t reassuring for defenders of religious liberty. He replied that “it’s certainly going to be an issue. I don’t deny that.” The Solicitor General could have hedged, but why bother? He figures that he has this case tagged and bagged, why not signal to the President’s constituencies that Obama’s Schmittian politics will proceed unabated to the end of his term. There will be more enemies to punish.

Given that we’re at play in Kennedy’s Council of Revision, did he himself give us a better rationale for a compromise, one that protects the dignified relational autonomy of religious membership along with finding a constitutional right to same-sex marriage? We can look to Kennedy’s concurring opinion in Hobby Lobby (2014) for a line of reasoning that actually provides a strong response to Verrilli’s barely concealed anti-clericalism.

In last year’s decision, Kennedy broached a high principle of religious freedom in America when he argued that

In our constitutional tradition, freedom means that all persons have the right to believe or strive to believe in a divine creator and a divine law. For those who choose this course, free exercise is essential in preserving their own dignity and in striving for a self-definition shaped by their religious precepts.

Keep in mind the incessant labor performed by the concept of dignity in Kennedy’s jurisprudence. Even federal marriage laws, Kennedy stated in United States v. Windsor (2013), can’t restrict the rights of states to recognize same sex unions as marriages and to confer upon those unions the dignity of lawful status.

The pressing difficulty here is that the dignity of religious belief for many may very well be denied the day after the Court’s momentous decision in Obergefell. Has Kennedy not given reason in his Hobby Lobby concurrence for protecting, in addition to sexual relational autonomy, institutional religious autonomy? As he wrote, religious belief is about more than just free belief, but also “the right to express those beliefs and to establish one’s religious (or nonreligious) self-definition in the political, civic, and economic life of our larger community.”

Voiced here is that institutional freedom, the kind that Verrilli was signaling he would trample, must also be supported if religious exercise is to have real meaning in our laws.

What is needed is in fact the full understanding of religious institutional autonomy that Kennedy has outlined.

Here we do well to recall the Court’s ringing endorsement—in which Kennedy joined—of the “ministerial exception” doctrine in the 2012 Hosanna-Tabor case. The Court there affirmed that religious freedom would wither absent a certain institutional autonomy from civil rights laws. Although the case was about a church’s right to fire a minister for its own reasons, its wider application includes protecting the integrity of institutional religious expression in education, charitable, and medical missions from the ever-expanding state. We could say that in 2012 the Court affirmed this “Freedom of the Church” as the indispensable aspect of religious liberty.

If the 50 states are to be required by the Court under the Fourteenth Amendment to recognize same-sex unions as marriage, surely our nation’s first freedom—religious exercise, and the dignity it finds in institutional expression—should not be disregarded.