Shakespeare on Law and Liberty

It is good to be reminded, at the fourth centenary of his death, that William Shakespeare (1564-1616) approached the relationship between law and liberty as a matter of arguing both sides of an interesting question.

This approach, where strong arguments invite counter-arguments and debate, inherently resists what T. S. Eliot called “the debauching of the arts by political criteria.” It also raises the stakes for citizens and subjects: oratorical skill is required when each side has a real point. Fortunately for Shakespeare, argumentum ad utramque partem was a staple of his humanistic education, which introduced schoolboys to the classical rhetoric of the great Roman lawyers.

In contemplating law and liberty, Elizabethans encountered a set of closely related issues, from the tensions between rule and misrule, as brought to life by Malvolio’s clash with Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night, to the threat of tyranny and the licensing of plays and printing presses—Shakespeare in the sonnets writes of “art made tongue-tied by authority”—to the silencing of Jesuits and Puritans excluded from the Elizabethan settlement in religion.

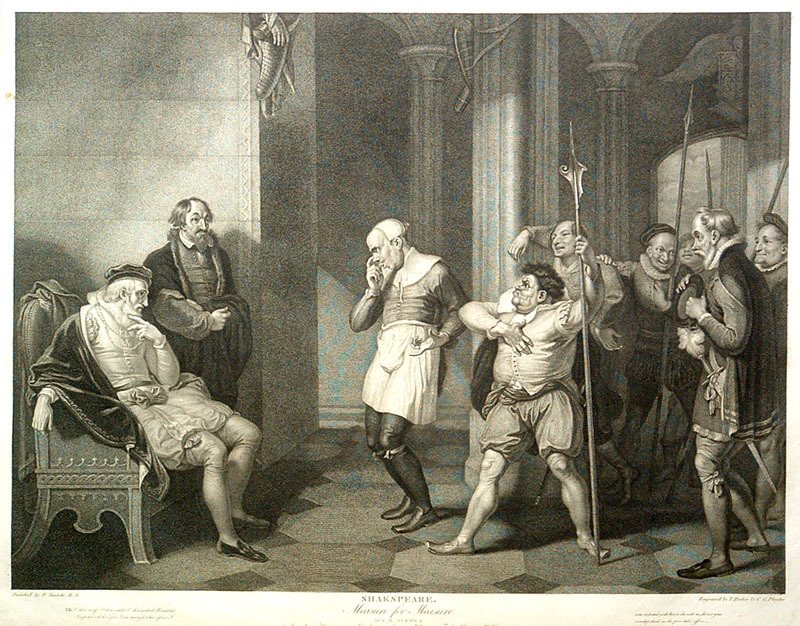

Often what propels the plot of a Shakespeare play forward is a legal question. Thus many of his characters reveal their true colors in argumentation over what the law demands. In Measure for Measure, for instance, Claudio’s imploring Isabella, “Sweet sister, let me live,” momentarily cools our sympathy for him, despite his receiving rough justice at Angelo’s hands, while Isabella’s heated response (“Oh, you beast!”) puts her own powers of sympathy in doubt.

“Blood hath been shed ere now,” Macbeth laments, “Ere humane statute purged the gentle weal.” Fearing Banquo’s ghost, he continues: “The time has been / That when the brains were out the man would die, / And there an end; but now they rise again.” Macbeth’s insane nostalgia for “humane statute” comes as a shocking revelation that tyrants will make the law an extension of their will.

In The Winter’s Tale, Leontes reaches the apex of his tyranny when he attempts to control Hermione’s trial: “There is no truth at all i’th’oracle.” / The sessions shall proceed.”

If we define equity as a means of tempering impersonal justice, requiring that we judge someone’s actions in light of his or her individual character and intentions, we may find the same half-conscious calculus of pity and fear qualifying our anger at Claudio or the penitent Leontes—or, on the contrary, stiffening our repugnance at Macbeth.

Shakespeare’s understanding of the natural relationship between law and literature turns the audience into an assembly of judges. Between the real law of his time and Shakespeare’s uses of it, we can, however, discern three important differences.

First, for the dramatist, law always serves an artistic purpose.

Even a topical satire, such as the skewering of Justice of the Peace William Gardiner as “Judge Shallow” in 2 Henry IV, survives as a work of literature and not a lawsuit, though the records of Shakespeare’s real-life legal skirmishing with Gardiner (who wanted to put Shakespeare out of business) were in fact unearthed around 1930. And while Shakespeare can, at times, wield legal language with admirable precision, he is not interested in law for its own sake. In the graveyard, Hamlet does not apply the technical terms of “fine” and “recovery” simply to charm a disputatious public: “Is this the fine of his fines, the recovery of his recoveries, to have his fine pate filled with fine dirt?” If the engineer is hoist by own petard, then the lawyer, too, must get his just deserts.

Shakespeare grasped the essentials of the natural law tradition, which aims to show that man in his rational nature is superior to beasts. The playwright cannot be classified, though, as a moralist upholding natural reason as the guarantor of human liberty and happiness. Natural law is degraded, in speeches of a forensic character, by intriguing if beastly men, including Shylock and Claudius.

But what do the more virtuous characters tell us? When the wise Portia rules against the usurer who pleads for justice, she hypocritically denies him the mercy that inspires her greatest flight of eloquence. Hamlet and Pericles rebel against incest, but syllogisms can save neither of them. The Duke of Albany sounds a dire warning: if “the heavens” do not intervene, “Humanity must perforce prey on itself, / Like monsters of the deep.” King Lear is a discouraging play for proponents of natural law, unless we read it as a commentary on what happens when natural law breaks down.

Second, Shakespeare rarely hands down an unambiguous ruling.

Pondering his invasion of France, Henry V is haunted by questions of legitimacy and Just War. To persuade young Henry and his court that he has a legitimate claim across the Channel, the Archbishop of Canterbury delivers the most labored speech in the Shakespearean canon, to the effect that the “Salic” law does not apply to France. This endlessly convoluted speech (“as clear as is the summer’s sun”) leaves Henry and his audience free to infer, not that Henry’s “claiming from the female” is no obstacle, but that his lawyers cannot help.

On the eve of the battle at Agincourt, the king disguises himself to visit the men in his camp. Henry tests a trio of soldiers by declaring that the king’s “cause” is “just and his quarrel honorable.” Michael Williams is a good man who replies bluntly, “That’s more than we know,” a justly skeptical remark that, along with the Archbishop’s legal opinion, unties the knot of certainty about the war’s justice.

And though, in the time of Winston Churchill, Henry V was a British national hero, Henry’s lonely speech, “O God of battles, steel my soldiers’ hearts,” does not lend itself, upon close analysis, to a mood of triumphal vindication. Henry is too aware that the “reckoning” at hand is beyond him. He pleads tortuously to God, “Not today, O Lord, / O, not today, think not upon the fault / My father made in compassing the crown!” Henry is neither hypocritical nor entirely self-deceiving: he is honest enough to know that he is in over his head. Not even his great victory overcomes the depth of our incapacity for judging such momentous questions.

Our third difference follows: Shakespeare, though by no means possessed of a revolutionary temperament, was less of a literary jurist than he was a skeptical Christian, an ironist for whom the Final Judgment called our legal judgments into question.

In this respect, let us revisit the graveyard scene in Hamlet:

FIRST CLOWN Is she to be buried in Christian burial, when she willfully seeks her own salvation?

SECOND CLOWN I tell thee she is; therefore make her grave straight. The crowner hath sat on her, and finds it Christian burial.

FIRST CLOWN How can that be, unless she drowned herself in her own defense?

SECOND CLOWN Why, ’tis found so.

FIRST CLOWN It must be se offendendo, it cannot be else. For here lies the point: if I drown myself wittingly, it argues an act, and an act hath three branches—it is to act, to do, to perform. Argal, she drowned herself wittingly.

SECOND CLOWN Nay, but hear you Goodman Delver—

FIRST CLOWN Give me leave. Here lies the water; good. Here stands the man; good. If the man go to this water and drown himself, it is, will he, nill he, he goes, mark you that. But if the water come to him and drown him, he drowns not himself. Argal, he that is not guilty of his own death shortens not his own life.

SECOND CLOWN But is this law?

FIRST CLOWN Ay, marry, is’t—crowner’s quest law.

SECOND CLOWN Will you ha’ the truth on’t? If this had not been a gentlewoman, she should have been buried out o’ Christian burial.

In the scene’s black comedy, the ruling on Ophelia’s suicide is left in the hands of the “crowner,” who is said to have “sat on her,” an almost obscene reminder that Roman lawyers sometimes referred to the rhetorical places of invention (who, what, where, when) as sedes or “seats.” The crowner, whose very title invokes the sovereignty of the crown, acts in the name of the king, as if Shakespeare were enjoying a subversive antithesis in crown and clown. It is the crowner’s ruling that the clowns question and ridicule.

As well they should. For the crowner is a stand-in not only for the crown, that is, the monarch who is a stand-in for God, but for the Lord God as well, insofar as the crowner presumes to determine by “quest law” (that is, through an inquest) what has been done “willfully.” And yet, in the final analysis, the crowner himself cannot possibly know the truth of Ophelia’s death. God alone can know that.

In effect, the crowner’s determinations are as irrelevant as the First Clown’s efforts at syllogisms and legal reasoning. Shakespeare, through his clown-speak, is reminding us about the limitations of earthly justice. He always assumed the reality of another judgment—beyond our quiddities and quillities, our cases, tenures, and our tricks—and wrote with it in mind.

Looking through a collection of essays published in 2013, Shakespeare and the Law, I was struck by Justice Stephen Breyer’s thoughtful comparison of the Bard to the ancients. Breyer sees a similarity between the “progression from ‘To be or not to be’ to ‘Readiness is all,’” and “the progression in Aeschylus’s Oresteia from the law of revenge to the establishment of formal justice.”

He goes on to suggest that Shakespeare’s Hamlet wants Horatio to tell his story, not so much in order to “justify himself,” as because he needs “to tell what has happened to him, spiritually, in the course of what we have seen in the play.”

We can only applaud the opinion of Justice Breyer in this case, for he upholds the Shakespearean perspective that justice is, in some pressing way, a spiritual need, to which all are subject in the end.