Two problems—war and kingship—should guide the viewer revisiting Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films twenty years later.

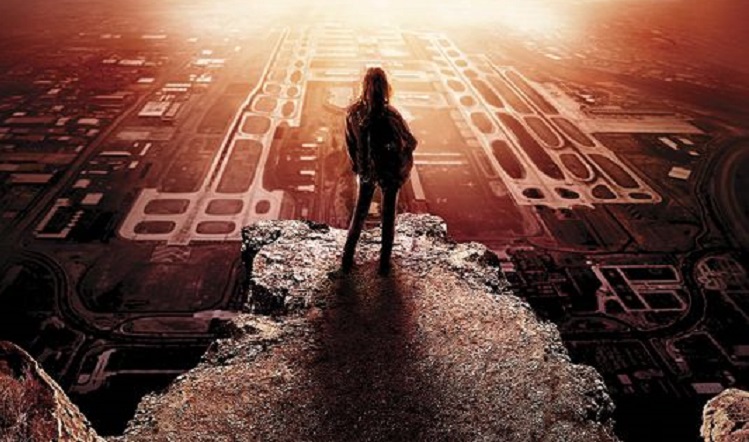

Rise of the Teen Dystopias

When Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games came out nearly a decade ago, it was a phenomenon. Named one of the best books of 2008 by Publishers Weekly, it spent a hundred weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, sold nearly 18 million copies, spawned two sequels, and was turned into a successful movie in 2012.

Collins did more than ensure her own success, however. Ever since J.K. Rowling’s first Harry Potter books became super-bestsellers in the late 1990s, the venerable genre of young-adult fiction grew to become the largest market for contemporary novels. Pure dystopias were rarely thought appropriate for young teen readers even then—not until the appearance of The Hunger Games somehow established them as a new subgenre. Publishers took Collins’ work as a template for the literary assembly line, and have been flooding the market with one dystopian series after another.

The Hunger Games was anticipated, to some degree, by Lois Lowry’s The Giver (1993), to say nothing of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), or H.G. Wells’s The Sleeper Awakes (1910)—although these were all written originally for adult audiences. But after it hit the jackpot young-adult authors were set free, or even encouraged by their publishers, to write partly political plots that were set in worlds notable for their grimness.

All one needs to do is point to three trilogies that have hit mini-jackpots: James Dashner’s The Maze Runner (the first volume published in 2009), Veronica Roth’s Divergent (2011), and Rick Yancey’s The Fifth Wave (2013). The movie interest has been spectacular: Between 2014 and 2016, major Hollywood studios brought two of Dashner’s, three of Roth’s, and one of Yancey’s to the big screen—together with films of two of Collins’ books and even a movie version of The Giver, a major box-office attraction over a decade after Lois Lowry wrote it.

The puzzle is why this model should be so replicable. Suzanne Collins’ achievement was preordained, to some degree. A successful writer of children’s television shows, she had reached the bestseller lists with The Underland Chronicles, her series of children’s fantasy novels, and her friendships in the New York publishing world ensured a large number of reviewers and publicists ready to praise her work. But why she and so many subsequent authors were drawn to dystopia remains a question.

The answer has something to do with publishing trends, the demand for girl-power stories, and an inchoate political sense among vaguely liberal authors that government is growing increasingly intrusive and authoritarian in the era of the Patriot Act that was passed after the attacks of September 11. But mostly, I think, the books derive from a hunger for political simplicity: a tale of clear right and wrong, a setting of understandable moral action.

The pattern-setting Hunger Games story is told by a 16-year-old girl named Katniss Everdeen. She lives in a coal-mining district—District Twelve, the last of the 12 districts of the nation of “Panem” (which loosely corresponds to North America). Panem is ruled over by a president who lives in The Capitol, a decadent but technologically advanced city that sneers at the people of the 12 districts.

Every year, each district is required to send one boy and one girl, from 12 to 18 years old, to fight to the death on a nationally broadcast television show. The point of this “reaping” for the nation’s Hunger Games is partly to satisfy the depraved taste of the sophisticates in The Capitol. Even more, the Hunger Games exist to remind the denizens of the 12 districts that they lost the old civil war: the riots and revolution that The Capitol suppressed to create Panem.

Only the contestant who outlasts all the others is allowed to escape the arena in which the games take place—the rest killed by the harsh conditions or their fellow competitors. When the lottery picks Katniss’12-year-old sister Primrose, Katniss (a good archer, thanks to her years of hunting to support her family) volunteers to take her place. She’s joined by Peeta Mellark, the baker’s son. Together they struggle through to win the tournament and, in a clever ploy, force the authorities to allow them both to escape. This unprecedented outcome proves very popular with those watching the television broadcast, but it makes an enemy of Panem’s president, which promises a doubtful future for Katniss.

The next two books in Collins’ trilogy—Catching Fire (2009) and Mockingjay (2010)—trace that future. Katniss fights her way through a second tournament and resists the government in The Capitol. In the end, she discovers a secret area, the supposedly destroyed District Thirteen, and helps found the revolution that will overthrow the corrupt power of Panem.

James Dashner’s Maze Runner books may seem different, since they center around a male main character, a teenager whose emotions and experience the third-person narration follows closely. He knows that his name is Thomas—but that is about all he remembers about his past. As the story opens, the boy is thrust out of an old elevator into the middle of a giant labyrinth. Discovering giant slug-robots called Grievers, he quickly joins other amnesiac teenagers wandering the dangerous maze.

The “runners” are the faster children, the ones the group picks to run ahead and map the maze. Gradually, Thomas figures out that the constantly changing walls of the maze may actually contain a code that points to a way out. In the closing moments, in desperation, the teenagers decide to attempt to break through the possible but unlikely exit their decoding has suggested—and they do break through. As they escape the maze, they’re greeted by a group of adults who take them to a sanctuary and tell them about an apocalyptic disease called “The Flare” that destroyed half the world.

Unfortunately, the people who met them on their escape prove to be only another stage of the cruel experiment being performed on the teenage geniuses. A spate of subsequent volumes followed: The Scorch Trials (2010) and The Death Cure (2011), together with a pair of prequels, The Kill Order (2012) and The Fever Code (forthcoming in September). And in them, the stories slowly reveal that the teenagers are actually the avatars of the scientists held responsible for the creation of the disease. They have to find out the truth and discover a cure for The Flare. Even more, an evil government has arisen in the wake of The Flare, and the young people have to escape its punishments and find a way to overthrow it.

Veronica Roth’s Divergent trilogy follows almost the same pattern. The first book opens (in first-person, present-tense narration) with a girl named Tris Prior, who lives in a future dystopia. It’s a world with everyone separated into five factions. When people reach adulthood, they are required to choose a faction in which they must stay for the rest of their life.

Tris chooses to join Dauntless, a faction known for its daring and bravery. But her initiation ceremony reveals that she is “divergent”—a person who can never belong to just one faction. Told to keep her divergent status hidden, Tris starts uncovering the secrets of the repressive government. She decides to form a small group of revolutionaries and prod the culture into revolution. Through subsequent books—Insurgent (2012) and Allegiant (2013)—she discovers that (as in The Hunger Games) she is in an arena fight. More, she finds that (like The Maze Runner) her performances are being secretly watched from an outside and superior world.

This sense of being watched seems to run through these books. Rick Yancey’s Fifth Wave trilogy is superficially different, in that each volume centers around a different main character and the opponents are space aliens who have captured the earth. In The Infinite Sea (2014) and The Last Star (2016), young people battle the oppressive rule of the aliens—with the aliens often taking human shape and pretending to lead the resistance to the aliens.

All the books, from The Hunger Games on, share a kind of uniformity of plot and perspective. What drives that is undoubtedly money: When one style of book succeeds, it’s bound to produce imitators. Dashner’s Maze Runner books deserve some credit for having a male main character. None of these recent dystopias are loudly feminist, but they’ve all been produced in an era of publishing, for children and young adults, in which it’s more acceptable to have a strong female character than a male one.

These books occasionally have a religious or supernatural element, but it is at best a thin one. Their worlds lack metaphysical or theological depth. The only arenas for important human action are political, since politics is the only place left where high-level deeds of right or wrong can take place. It’s as if these are dystopias because they have to be. They have to simplify the political order down into something close to pure evil, in order to provide their heroines and heroes a chance to do pure good.

Why is it any surprise that they all have young characters who grow into heroic figures operating in a world ruled by dictatorial powers? The authors all seem to have a vision of a heroic French Underground, struggling to fight a Nazi regime. In a way, that’s a very liberal view of both heroism and bad government: all intrusive government is equated with Nazism, and all heroic action is reduced to secret cells of political revolt. It’s the same impulse that equated George Bush and Adolf Hitler, and saw the Patriot Act as almost akin to the Nuremberg Laws.

As the books expand their worlds, some development takes place. Typically, there’s an equation of Nazism and capitalism, which could be attributed simply to the authors’ naive political theory. More interesting is the way in which nearly all of them approach a not-fully-formed libertarianism that is suspicious of all government. Casting a strong government as the villain leads, by the logic of storytelling, to a demand to abolish strong government. And it may be partly because qualms about surveillance by the National Security Agency have been felt not just by liberals but also by libertarians, who had a well-developed critique of governmental invasion of privacy before the age of anti-terror monitoring.

Then, too, we cannot forget that the heroic tale is an individual story, in its essence. It’s about a particular hero or heroine, and the individual always has to stand out from the crowd to make the story-telling work.

Mostly, though, this Hunger Games kind of young-adult fiction has blossomed because it satisfies a hunger for clear vices and clear virtues. The authors seem unable to cast their stories on a metaphysical plane, so they have to find right and wrong in a political setting—and the political setting has to be extreme enough, so overwhelmingly dystopian, that right and wrong are clear even for authors suspicious of any claim about moral authority.

In other words, the authors share J.R.R. Tolkien’s desire for a world of right and wrong but they are not inventive enough to imagine a Tolkien-like fictional world in which small actions and great wars echo the cosmic struggle between good and evil. So they terrestrialize their tales. It as though George Orwell’s 1984 met Gladiator, and together they spawned a young-adult fiction about heroic teenagers saving the world.