To move forward on race relations, we first need to understand the inherent complexities about slavery and slaver-ownership.

Liberate the Captives

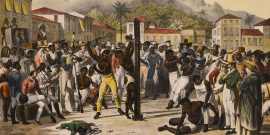

The Birth of a Nation has been called a classic revenge movie—Braveheart set in antebellum America—and it’s a largely accurate assessment. This is a biopic of Nat Turner, a slave who led a rebellion in 1831 of slaves and free blacks in Southampton County, Virginia, that resulted in the deaths of some 55 to 65 white people. In retaliation, white militias and mobs killed more than 200 black people before hanging Turner.

Something crucial has been left out of that assessment, though. Whereas the William Wallace of Mel Gibson’s Braveheart (1995) revolted based on his innate, natural law knowledge about the evil of the British overlords who controlled his land and family, Nat Turner believed that he was explicitly charged by God to confront his oppressors. While this is a theme for writer-director Nate Parker, who also plays the lead role, there’s not nearly enough of it.

It opens during an African initiation ritual, during which the young Nat Turner is recognized as possessing “holy marks”—three raised moles in a straight line down his chest—as well as prophetic powers of wisdom, courage and vision. As a boy, Nat becomes friends with the son of his owner Samuel Turner (Armie Hammer), and takes books from the big house’s library to learn how to read. Sam’s mother (Penelope Ann Miller) begins to tutor him in the Bible, and Nat begins preaching. “You’re a child of God,” his father tells him. “He gave you a purpose.” Nat has a vision, black angel surrounded in dazzling white light.

The tension in The Birth of a Nation is not between Nat and his visions, but between the slave and the Bible. Turner is such a good preacher that he is soon sent to enslaved communities in order to defend slavery and prevent an insurrection, but he begins to notice that the Bible that tells slaves to obey their masters also talks a great deal about liberation.

Turner also falls in love with a slave named Nancy (Aja Naomi King). Some the best scenes in the film are of Nat and Nancy getting to experience love in the midst of unimaginable misery. After a beautiful wedding scene, there is a lovely shot of the two newlyweds silhouetted against a moonlight window, a candle burning between them. Soon after Nancy is raped by a group of white men, and then another woman, Esther (Gabrielle Union), is also raped by a businessman who has the power to bring long-lost prosperity back to the Turner plantation. These scenes are horrific, although Parker keeps the violent scenes short, well shy of Quentin Tarantino’s lurid Django Unchained (2012).

As Turner witnesses more and more inhuman abuse of slaves, he gradually turns from preaching resignation (“Slaves obey your masters”) to violent liberation. He has a vision of blood seeping in red bubbles through the silk of an ear of corn, then defies master Samuel by baptizing a white man on the grounds of the plantation, and as a result endures a severe beating. This is a profound foreshadowing of the forgiveness of the civil rights movement—after dipping the white man into the river, Turner himself seems a little bewildered and awestruck by the power of what he has just partaken in.

Technically, The Birth of a Nation is accomplished in every way. The cinematography by Elliot Davis is rich, and the editing and pacing crisp and assured. The music is moving and only rarely overpowering. Parker has an expressive face, able to convey deep, soulful sorrow with his eyes, and his understatement puts the brutality he is witnessing into sharp relief. The violence here is at times graphic and stomach-turning. In one scene, a slave who is on a hunger strike has his teeth knocked out and is force fed through a tube. Yet the scenes are never punishingly drawn out (again a specialty of Tarantino).

What is missing from the film is a proper indication of Turner’s fiery mysticism. An informative article by Patrick Breen in this month’s Smithsonian magazine highlights not only Nat Turner’s confessions, but his visions. Breen delves into The Confessions of Nat Turner, the account of the revolt published in 1831 by lawyer Thomas Ruffin Gray. Basing himself on that account, Breen observes that

while Turner valued the Bible, he rejected the corollary that scripture alone was the only reliable source of guidance on matters religious and moral. Turner believed that God continued to communicate with the world.

He claimed that God communicated with him. “The Lord had shown me things that had happened before my birth,” Turner is supposed to have said, and on May 12, 1828, “the Spirit instantly appeared to me.” When asked by Gray what he meant by the Spirit, Turner is said to have responded: “The Spirit that spoke to the prophets in former days.”

To Turner, stars were really “the lights of the Saviour’s hands, stretched forth from east to west.” In the field, he found “drops of blood on the corn as though it were dew from heaven.” When he saw “leaves in the woods hieroglyphic characters, and numbers, with the forms of men in different attitudes, portrayed in blood,” he was reminded of “figures I had seen in the heavens.”

Breen writes that “the most consequential signs appeared in the months prior to the revolt,” and these included a solar eclipse, “which Turner interpreted as a providential signal to start recruiting potential rebels.” When the sun was occluded, “the seal was removed from my lips,” said Turner, “and I communicated the great work laid out for me to do, to four in whom I had the greatest confidence.” These were his first co-conspirators. Here is Breen again: “In August, a sun with a greenish hue appeared across the eastern seaboard. Turner immediately understood this peculiar event as a signal from God that the time to begin the revolt had arrived.”

Breen compares Turner’s views on private revelation to “those of his contemporaries Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, and William Miller, the father of the Adventist movement. Turner’s views were clearly unacceptable to the whites who controlled Southampton’s interracial churches.”

This rich material is missing from the film, and it is the weaker for it. The last 30 minutes do indeed turn The Birth of a Nation into an American Braveheart, which is to say a bloody revenge rampage. Unlike so many Hollywood revenge fantasies, which usually revolve around women and guns, the payback in Birth feels justified, even thrilling. Parker has meticulously built up the case for it. Being kidnapped from your home, forced into brutal labor, whipped, and forced to do nothing while your women get raped and abused is a pretty good case for self-defense.

After setting the Biblical contradiction between slaves ordered to obey their masters and the theme of liberation from bondage, Parker doesn’t fully delve into the alternative possibilities: Not only God as conscience, but God as natural mystic who can be heard not through scripture of reason but the stars, the wind, the natural world itself. This crucial and dynamic connection between Turner and the divine would translate naturally to film—just see the work of Terence Malick. Yet Parker doesn’t fully explore it. It’s a missed opportunity in what is otherwise a power and even important film.