Many of my contributions to this blog will riff my forthcoming tome on the Constitution and its federalism, cleverly entitled The Upside-Down Constitution. The publisher’s (Harvard University Press) release date is February 15. However, you can already pre-order the book on Amazon.com. What exactly is “upside-down” about our Constitution? Keep reading to find out.

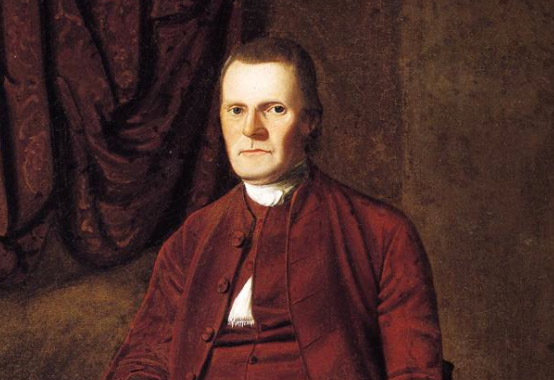

Roger Sherman: An Old Puritan in the New Republic

Connecticut’s Roger Sherman was the only Founder to help draft and sign the Declaration and Resolves (1774), the Articles of Association (1774), the Declaration of American Independence (1776), the Articles of Confederation (1777, 1778), and the U.S. Constitution (1787). As a member of the first federal Congress, he played an influential role in drafting the First Amendment.

Yet when Supreme Court justices have turned to history to interpret the Establishment Clause, they have referenced Sherman only three times. By way of contrast, Thomas Jefferson, a man who played no role in drafting or ratifying the amendment, is referenced 112 times.

One needn’t be cynical to suspect that justices who prefer Jefferson to Sherman are not really interested in understanding the “generating history” of the First Amendment (about which see my introductory post for this series, featuring participants in the debates of the Founding era over religious liberty and church-state relations). Instead, they are looking for a useable history, one that helps them to build a wall of separation between church and state. Because Sherman did not support such a wall, they ignore him.

Roger Sherman (1721-1793) is important in his own right, but his views on religious liberty and church-state relations are also representative of the 50 to 75 percent of the Founders who were Calvinists. He certainly reflects their views far better than the nominally Anglican Madison and Jefferson (about 16 percent of Americans were Anglican at that time).

By the late 18th century, Calvinists were scattered throughout America, but Connecticut was absolutely dominated by them. They accounted for 85 to 90 percent of the state’s population. America’s break with Great Britain could have been devastating for Connecticut’s religious dissenters. Earlier, the colony had been forced to tolerate Quakers, Anglicans, and Baptists because of Parliament’s 1689 Act of Toleration. Now that Connecticut was a state, and one no longer bound by this law, it could expel these non-Calvinists or limit their rights.

In 1783, Connecticut’s General Assembly charged Roger Sherman and the aptly named Richard Law with the task of revising the state’s laws. Among Sherman’s contributions was “An Act for Securing the Rights of Conscience in Matters of Religion, to Christians of Every Denomination in This State.” This act, which was approved by the legislature with few changes, guaranteed religious liberty for all citizens—including Quakers, Anglicans, and Baptists.

An obvious but anachronistic objection to the act is that it does not protect non-Christians. There are no records of any citizen in the state being anything other than a Christian, so it is a mistake to read too much into this limitation.

Separationists ignore Sherman not because of his views of religious liberty, but because he believed that protecting it was compatible with governmental support for Christianity. Indeed, even his religious liberty statute begins: “As the happiness of a People, and the good Order of Civil Society, essentially depend upon Piety, Religion and Morality, it is the Duty of the Civil Authority to provide for the Support and Encouragement thereof.”

Other statutes drafted by Sherman and Law created a system whereby citizens were taxed to support the churches they chose to join. Excellent arguments can be made against this sort of multiple establishment, and eventually Connecticut’s civic leaders became convinced by them—but not until 1819. At the time, many Founders embraced both religious liberty and state support for Christianity.

(As an aside, it should be noted that the revisions also included a gradual manumission statute that put slavery in the state on the road to extinction. That statute was likely drafted by Richard Law, but there is every reason to believe that Sherman, a life-long opponent of slavery, supported it.)

In 1788, Sherman was elected to be one of five members of Connecticut’s delegation to the U.S. House of Representatives. His colleague from Virginia, James Madison, fulfilling a promise made to his constituents, pushed the House to adopt a bill of rights. Representative Sherman originally dissented, pleading that there was more important business to which to attend. But once Congress began debating possible constitutional amendments, he was an active participant.

To consider the many proposed amendments, the House created a select committee composed of one member from each state. Sherman represented Connecticut. There are no records of the committee’s deliberations, but it produced a draft bill of rights in Sherman’s handwriting. This the only handwritten draft of the Bill of Rights known to exist.

Madison’s first draft of the Bill of Rights contained proposed amendments that would have been interspersed throughout the Constitution. Sherman objected, contending that “we cannot incorporate these amendments in the body of the Constitution. It would be mixing brass, iron, and clay.” Sherman won the point.

Two months after ratification of the Constitution, on August 15, 1788, the House turned to Madison’s proposal to insert the phrase “No religion shall be established by law, nor shall the equal rights of conscience be infringed” into the document’s Article 1, Section 9. Sherman considered the amendment “altogether unnecessary, insomuch as congress has no authority whatever delegated to them by the constitution, to make religious establishments, he would therefore move to have it struck out.” Sherman lost this battle, although the wording of Madison’s proposal was altered significantly.

Sherman did not join the remaining debates over what became the First Amendment, but he did contribute to discussions of the second provision concerning religion to come before the House. Madison had proposed that the Second Amendment include this language: “No person religiously scrupulous, shall be compelled to bear arms.” Although largely forgotten today, this provision provoked almost as much recorded debate as the First Amendment’s religion provisions.

When Georgia’s James Jackson suggested that persons exempted from military service should be forced to pay for a substitute, Sherman objected:

It is well-known that those who are religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, are equally scrupulous of getting substitutes or paying an equivalent; many of them would rather die than do either one or the other—but he did not see an absolute necessity for a clause of this kind. We do not live under an arbitrary government, said he, and the states respectively will have the government of the militia, unless when called into actual service . . .

Sherman was sympathetic to the plight of pacifists, but he preferred to rely upon state and federal legislatures to protect them. Madison’s proposal was eventually rejected by the U.S. Senate, but Madison and Sherman were later able to include a similar provision in the nation’s first militia bill.

Madison did not trust states to protect rights, so he offered an amendment stipulating that “No state shall infringe the equal rights of conscience, nor the freedom of speech, or of the press, nor of the right to trial by jury in criminal cases.” This restriction on the states, which Madison conceived “to be the most valuable amendment on the whole list,” occasioned little debate, and with minor revisions was passed by the House. However, the Senate rejected the proposed amendment, and Madison was unable to save it.

After additional debate in each body, Madison, Sherman, and Representative John Vining of Delaware were appointed to a conference committee to reconcile the two chambers’ versions of the amendments. The Senate appointed Sherman’s protégé Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut to head that body’s delegation. He was joined by Charles Carroll of Maryland and William Paterson of New Jersey, and the committee’s conference report was eventually penned by Ellsworth.

On September 24, the House approved the conference committee’s version of the bill of rights with a few minor changes. The next day the Senate approved the 12 amendments passed by the House, and they were sent to the states where the 10 that we now know as the Bill of Rights were ratified.

The Founders differed with respect to whether and/or how civic authorities should promote religion. On balance, Reformed Christians like Sherman were sympathetic to significant state support for Christianity, as suggested by the survival of establishments in Vermont (1807), Connecticut (1819), New Hampshire (1819), Maine (1820), and Massachusetts (1833).

Congress clearly intended the Establishment Clause to prohibit the creation of a national church, but few thought it created a high wall of separation between church and state. This can be demonstrated in a variety of ways, but one useful exercise is to consider other actions taken by the first Congress. Notably, on the day after the House approved the final wording of the Bill of Rights, Representative Elias Boudinot of New Jersey proposed that the President recommend a public day of thanksgiving and prayer. In response to objections by South Carolina Representatives Aedenus Burke and Thomas Tucker that these practices mimicked European customs, and that such calls are properly issued by states, Sherman:

Justified the practice of thanksgiving, on any signal event, not only as a laudable one in itself, but as warranted by a number of precedents in holy writ: For instance, the solemn thanksgivings and rejoicings which took place in the time of Solomon, after the building of the temple, was a case in point. This example he thought, worthy of Christian imitation on the present occasion; and he would agree with the gentleman who moved the resolution.

The House approved the motion and appointed Boudinot, Sherman, and Peter Silvester of New York to a committee to meet with senators on the matter. The Senate concurred with the House’s motion, and Congress requested that President Washington issue his famous 1789 Thanksgiving Day Proclamation.

It is not unreasonable to call James Madison the “Father of the Bill of Rights,” but as this discussion has shown, he did not act by himself. Sherman and other members of Congress played important roles in crafting these amendments. Many of these men were also active in religious liberty and church-state controversies at the state level. Anyone interested in the “generating history” of the First Amendment needs to consider the broad constellation of Founders, not just one or two of them. When one does this, the assertion that the Founders desired to build a wall of separation between church and state becomes completely untenable.

An originalist understanding of the Establishment Clause permits the national government, and by extension the states, to promote religion. But it does not require them to do so. There are excellent theoretical, theological, and prudential reasons to keep civic officials out of this business altogether.

Saying that governments should not promote religion is not to say that they should not protect it. If we desire to remain faithful to the Founders’ vision, we should insist that civic leaders make every effort to defend what they called the sacred rights of conscience. And we need not be concerned that such efforts violate a constitutional a wall of separation between church and state.