If President Trump is going to break norms, he should at least aim to do it productively.

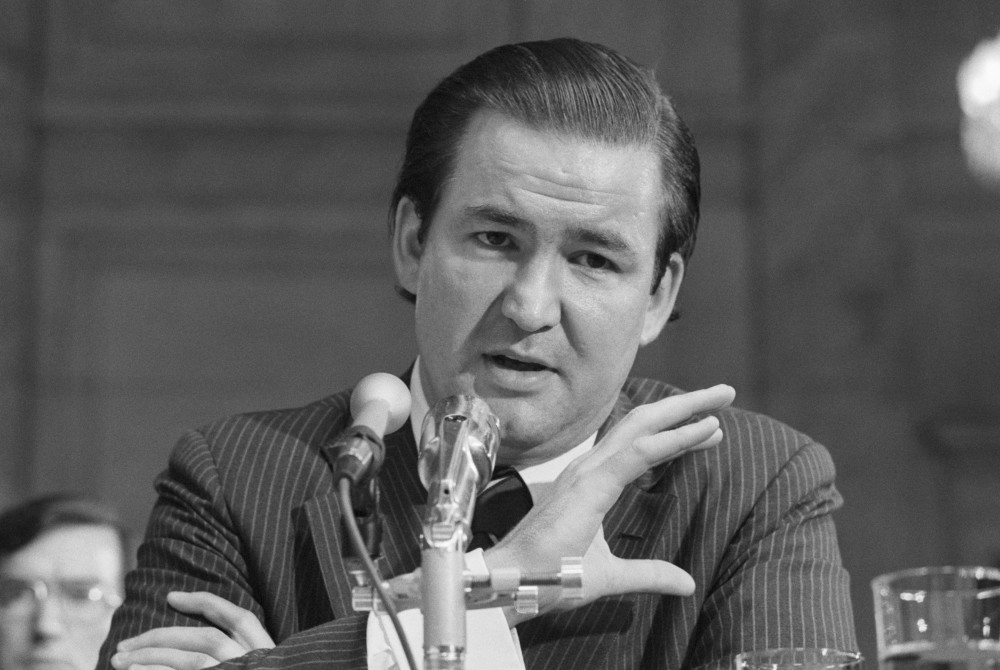

Portrait of a Speechwriter as a Young Man

When we read, in his new memoir, Patrick J. Buchanan’s statement that “To some of us, America was ceasing to be a democratic republic,” the thought is familiar coming from him. But this iteration takes us back to the Pat Buchanan of the 1960s and 1970s, who said and wrote such things staunchly, wittily, and combatively, as an affirmation of the beliefs of his father and mother, his family and friends, his teachers, his church, and his community growing up in the nation’s capital (a world that he skillfully evoked in a previous memoir, 1988’s Right from the Beginning).

Washington is a company town. Washingtonians tend to grow up wanting to become important inside the company, which is to say inside the government. Buchanan’s run at importance was notably successful. Nixon’s White House Wars: The Battles that Made and Broke a President and Divided America Forever takes readers through his filing cabinet, for it is built around the feisty memos that the Nixon speechwriter sent to his boss. It is a follow-up to The Great Comeback (2014), chronicling the years 1965, when he first became a Nixon aide, through the victory over Hubert Humphrey in 1968.

The matters treated in the Buchanan memos vary widely. Nixon didn’t always take his advice, the author admits. That didn’t stop him from “exploiting my role as his media analyst to make the case for policy changes,” he writes. Here is but a partial list:

- Nixon named the U.S. missile defense system the Safeguard system, on Buchanan’s suggestion.

- “Silent Majority” was from a speech the President wrote himself but it was, according to Buchanan, “a phrase I had given him in August 1968.”

- Buchanan urged Nixon to dial back excessive legal powers given to the new Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

- A 1971 statement directing that medical facilities on military bases follow state laws against abortion “was the President’s, but the language was mine.”

- Buchanan was called in to write the speech announcing the U.S. invasion of Cambodia along its border with Vietnam, an operation that stemmed attacks on our troops being launched from Cambodian sanctuaries by the communist North Vietnamese.

- When anti-Vietnam protests waxed on the National Mall and a group of attention-grabbing military veterans (including John Kerry) showed up, Buchanan believed it wise to treat them with kid gloves, and so “I wrote Haldeman to tell the President to tell Justice to back off.”

- When Defense Department analyst Daniel Ellsberg leaked to the press a secret DoD history of the war (a.k.a. the Pentagon Papers), the White House decided not to let the FBI handle it but to “conduct its own investigation,” and “the individual the President wanted to oversee the investigation . . . was me.” (Buchanan declined the assignment.)

- He tried to persuade President Nixon to remove an aging J. Edgar Hoover as head of the FBI.

- He wrote the veto message when the President vetoed the Child Development Act of 1971.

- On the eve of the 1972 Democratic presidential primary in Wisconsin, he wrote to Nixon that “we should have Republicans cross over and vote for George McGovern. Word should go forth today. PJB.”

- “Asked to provide a Q&A for the First Lady when the [Watergate] indictments came down, I wrote out a page and half and sent them to John Dean.”

- Buchanan got Father Theodore Hesburgh fired as chairman of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

- “As soon as the Ziegler briefing had ended, I had said the only realistic course was the immediate resignation of all three—Dean, Haldeman, and Ehrlichman.”

- He advised Nixon to fire Archibald Cox, the Watergate special prosecutor.

Does all this add up to Pat Buchanan’s being to Richard Nixon what Colonel House was to Woodrow Wilson? Well, we would be falling too hard for the self-interested authorial view if we drew that conclusion. Checking against other sources reveals the possibility that some items have been a tad inflated, in the way of Washington insider memoirs. Henry Kissinger’s The White House Years (1979) offers a distinctly different account of the drafting of the Cambodia speech. According to Strictly Right: William F. Buckley Jr. and the American Conservative Movement (2007) by Linda Bridges and John R. Coyne, Jr., the one who actually thought up the “Silent Majority” phrase was a man named Otto Scott.

Then, too, the complexities of Nixon the man were reflected in a politically complex administration. Bridges and Coyne describe the overall picture—and Buchanan might not disagree—by saying that “unfortunately, Nixon put the task of building his new political majority in the hands of H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman,” his ideologically colorless chief of staff and domestic affairs advisor. “Others, like Pat Buchanan—the one true conservative among the top staff—were too close to Nixon personally to be denied access. However, their influence on policy was minimized.”

Even indexing for inflation, it still can be said that for a mere speechwriter-cum-media analyst, “PJB” made his mark. The anti-Establishment speeches he wrote for Vice President Agnew electrified conservatives and drew middleclass and working class people to the GOP’s message. The intellectuals Buchanan cultivated, whose writings he touted, were a significant part of the coalition of conservatives and neoconservatives that would help the next Republican President come to power, and that would influence Ronald Reagan’s policies once in power.

The years before Nixon took office in January 1969 saw waves of urban rioting and segregationist resistance to civil rights laws. But the Nixon administration proceeded to calmly and effectively implement the school-desegregation orders flowing from the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Buchanan quotes a liberal New York Times writer on the Nixon administration’s “accomplish[ing] more in 1970 to desegregate Southern school systems than had been done in the sixteen previous years.” In the South in 1968, 68 percent of African American children attended exclusively African American schools. “By 1972,” writes Evan Thomas in Being Nixon: A Man Divided (2015), “only 8 percent did. There were fierce battles ahead over court-ordered busing, but Nixon had achieved a milestone in race relations.”

One of those doing battle, of course, was Buchanan. He describes “acrimonious infighting in the White House” over busing, and his attempts to spur the executive branch to push back against the judicially mandated busing of school children to achieve racial integration. Buchanan wanted to confront the Supreme Court on it, but Nixon did not.

Buchanan’s views on matters like busing and abortion were based on principle, but the thrust of his advice to Nixon was how to turn them to practical use. For the mid-term election of 1970, he wrote to the President:

We should attack the ‘liberal Eastern Establishment,’ and target the real swing voters—the ‘Daley Democrats . . . the law and order Democrats, conservatives on the ‘Social Issues,’ but ‘progressive’ on domestic issues.’ This is the [Ben] Wattenberg thesis—and I think it is basically correct.

Nixon “agreed with my analysis and strategy,” he writes. It yielded only so-so results in the 1970 election, but in 1972, “we drove wedges through the ideological, cultural-moral, economic, and sectional fissures” in the Democratic Party. Nixon won his (short-lived) second term that year by a landslide. And not for nothing is Buchanan referred to as the “ideological godfather of Trumpism”—its time would come.

Conventional wisdom would say that all Richard Nixon did on the race question was stage awkward photo-ops with Lionel Hampton. Wrong. Conventional wisdom, however, on the political chicanery that Nixon countenanced among his staff is rather more confirmed by this book than not. Buchanan countenanced it too, up to a point. But the speechwriter, having steered clear of leading the “Plumbers” tasked with tracking down administration leaks to reporters, was free to go on the political offensive against the Senate Watergate Committee when he was called to testify.

His answers, during five hours of live television, tracked closely with his strategy memos to Nixon. He scolded the senators and staff investigators for a campaign of vilification against him, Buchanan, that had been carried out by the “tremendous interlocking directorates” of the liberal media and the Democratic Party. He lambasted the “dominant political establishment of the country”—a pack of turncoat-on-Vietnam elitists “against which you might set, to be simplistic, Mr. Nixon and his Middle American constituency.” Time magazine, cited here, called Buchanan “easily the Administration’s most effective witness to date.”

Behind the scenes, the hardliner Buchanan was arguing to the President and his team that the White House tapes—at least those not subpoenaed by the special prosecutor—should be destroyed. Stubbornly he claims even now that this would have saved Nixon’s presidency. His logic breaks down. Appearances matter in these situations, as he acknowledges along the way, and surely disposing of any audio tapes, even if legal, would have come to the public’s attention and been seized on as more evidence of a cover-up.

The nimble performance before the Watergate Committee turned Buchanan into a public figure overnight. He doesn’t say so directly, but clearly this is what spurred him to imagine himself running for President. That this office has eluded him, while a far less knowledgeable and articulate person inhabiting his positions took over the GOP and did win the presidency, carries several ironies.

Just after Nixon resigned came Buchanan’s announcement (in his 1975 book Conservative Votes, Liberal Victories) that “The hour may be approaching for conservatives to dissolve a popular front with the Republican party that no longer seems to serve their political interests.” The hour took its time in arriving, considering that in 1985 Buchanan went to work in the Reagan White House. But it arrived eventually as he became, in the presidential elections of 1992, 1996, and 2000, the populist peeling votes away from the mainstream Republican candidate. By the 2000 race, he was no longer a Republican but a Reform Party candidate, with a running mate from the John Birch Society. (Her name was Ezola B. Foster, and she joined the ticket after the Teamsters’ James P. Hoffa, Jr. turned him down.)

He voices the same social conservative and class-conflict themes he always did. But his odyssey outside of the party he helped to shape has curdled his rhetoric. Parties do discipline people, which this book shows in interesting ways.

The America First sentiments he only hinted at as a White House staffer in 1972 became full-fledged worship of Charles Lindbergh later. The idea is rather amusingly planted here, in the anecdote where he’s telling H.R. Haldeman not to reflexively dismiss George McGovern’s foreign policy stance, for isolationism is as American as apple pie. We also know from this book that the Buchanan of yore considered the leaker of the Pentagon Papers a traitor. Nowadays Buchanan is quicker to condemn the U.S. government than Edward Snowden, “who showed up at the Moscow airport, his computers full of secrets that our National Security Agency has been thieving from every country on earth, including Russia.”

The Buchanan of yore came up with talking points on how Republicans might raid the Democratic Party for Southern Protestant, Northern Catholic, Jewish, and black votes. He advocated, regarding the Catholics, that they be appealed to with offers of federal aid to parochial schools. In subsequent years Buchanan had, to put it mildly, a falling out with the Jews over Israel, the Iraq war, and much else. Proudly he recalls here that he scripted Nixon’s biting condemnation of the racism of Alabama Governor George Wallace. The latter-day Buchanan typically addressed President Obama in terms such as these: “Barack talks about new ‘ladders of opportunity’ for blacks. Let him go to Altoona and Johnstown, and ask the white kids in Catholic schools how many were visited lately by Ivy League recruiters handing out scholarships for ‘deserving’ white kids.”

It’s intriguing to compare two Reform Party figures from the 2000 election campaign, candidate Patrick Buchanan and major donor Donald Trump. As can be seen in this television interview from back then, the aspiring politician Trump wanted the Reform Party to overcome the leftwing extremism of Democrats and the rightwing extremism of Republicans. That’s what he said, anyway—that he wanted a third party of the sensible center. Buchanan’s plan for the Reform Party, in contrast, was to use it to punish the two major political parties for their homogeneity. Buchanan proudly ran from the fringe.

“America First” was an electoral winner in 2016. On the other hand, given Trump’s protean career, and his unpredictability, who is to say the country won’t end up with the more ideologically colorless variety of Republican administration? Will he go Buchananite on immigration, trade, social conservatism, anti-interventionism—or does his real political self more closely match the liberal Republicans he talked up in the television interview? Whether his brusque, Buchananite tone is meaningful in the long term, only time will tell.