A Proletarian Lot Promoting Capitalism

Newspapers are a dying communications medium yet the Wall Street Journal, which first saw print in 1889, is still going strong. It has schooled generations of conservatives, and I say that as one who only recently became a daily subscriber. A look through my basement filing cabinets (some people have not yet made the transition to paperless) would turn up countless clippings from editions of the Journal that have found their way to me over the years. Many would be editorials carrying no byline; many others would be signed editorial features and op-eds, including “Global View” columns by George Melloan.

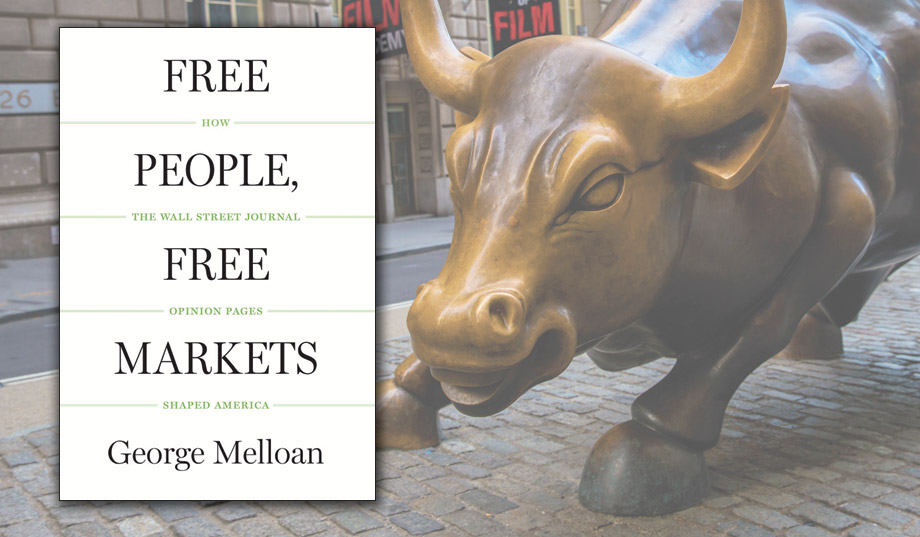

Melloan worked for the Journal from 1952 to 2006. His Free People, Free Markets: How the Wall Street Journal Opinion Pages Shaped America is a kind of scrapbook. It contains an institutional history going back to the paper’s founding, a travelogue of the far-flung places from which the author wrote his column, remembrances of his colleagues, a precis of the news developments covered by the Journal from the 1950s to the present, and a meditation on the lessons of political economy that he gleaned as a practitioner of foreign affairs journalism and a student of thinkers like Jean-Baptiste Say and Milton Friedman.

It all started at Broad and Wall Streets in Manhattan, writes Melloan, “in a barren basement room down some steps to the rear of a soda fountain,” when Charles Dow, Edward Jones, and Charles Bergstresser, the distributors of a daily, hand-written bulletin of financial and business news, bought a hand-operated printing press. Dow, “the philosophical and ethical pillar of the operation,” insisted that the fledgling publication steer clear of “the constant offers of bribes from brokers and investors to reporters willing to promote their stocks.”

It was also Dow who decided that the paper would cover a wider array of subjects than stock-and bond-trading. An Englishman named William Peter Hamilton brought the thinking of Adam Smith and John Locke to the Journal’s pages. The like-minded C.W. Barron, a rotund eccentric, world traveler, and non-stop writer of newspaper copy (whose eponymous financial publication is still a going concern), moved among the famous and powerful of the Eastern seaboard and boosted the Journal’s prominence in the World War I era.

The most colorful figures in the book are Barron and Jude Wanniski, the irrepressible reporter and popularizer of supply-side economics who got fired from the paper in 1978 for handing out leaflets for a Republican senatorial candidate. Others may be less colorful, but they demonstrate an interesting fact: that this East Coast journalistic powerhouse and its crown jewel, its editorial page, have been largely run by a string of midwesterners, stretching back to a Hoosier named K.C. “Casey” Holgate, in the 1920s.

The self-described “Indiana farm boy” George Melloan came to the Chicago bureau of the Wall Street Journal in 1952 from the Muncie Press. One of his many writing and editing roles at the paper was as deputy to the editor of the editorial page, the late Robert Bartley, a Minnesotan. There have been a number of Ohioan managing editors, and the successor to Bartley as editorial page editor is Wisconsin’s own Paul Gigot. This reviewer’s sense (as expressed previously in this space) is that the sophistication of the Wall Street Journal, which over the years has added arts-and-leisure coverage, a real estate section, and other glitzy New York Times-like features, has benefited from a good dose of midwestern straightforwardness and common sense.

Melloan writes that from Dow onward, the Journal’s editors saw that “integrity had market value.” He protests against the assumption that a paper that many consider “the Republican Bible” is therefore the Voice of Business. Its liberal critics threw “class warfare barbs” at the Journal’s editorial page in the 1970s and 1980s, when Wanniski, Bartley, and other iconoclastic writers and academics were waging a campaign, and a highly successful one, to cure the policymakers in Washington of Keynesianism. The truth was that

We were a rather proletarian lot to be promoting capitalism, but we were not at all out of step with the special brand of populism that had been made a tradition by our predecessor Journal editorial page writers. ‘Free people, free markets’ was in our veins for the simple reason that those principles allowed upward mobility for individuals with energy and ambition—people like us.

With relish Melloan narrates a battle for journalistic probity that he says made the newspaper’s reputation in the modern era. This was back when he was in the Chicago bureau. At the time, American carmakers brought out new models with much fanfare but little to no advance press. This was preferable, the carmakers said, because divulging the details about next year’s product would hurt sales of their soon-to-be-obsolete cars of the waning model year. Reporters on the automotive beat always complied; that is, until the Journal’s Detroit bureau decided this taboo was wrongly depriving consumers of information. In 1954 the bureau broke the taboo, printing a front page story about Detroit’s new designs for 1955.

General Motors, a major Wall Street Journal advertiser, withdrew its ads and accused the paper of stealing GM property. Editor Barney Kilgore (another Hoosier) didn’t give in. Instead he had the Detroit bureau step up its coverage of GM. The rest of the journalistic fraternity even ostracized the Journal for a while, incensed that their acquiescence in censorship was being exposed. Kilgore ended up meeting personally with GM’s president, and it was the car company that caved. Writes Melloan: “The effect on news staff morale was electric. We were working for an honest newspaper!” He quotes a Journal advertising manager to the effect that readership then “began a rapid climb that would make it the nation’s largest-circulation newspaper.” (The advance reportage didn’t depress automotive sales in 1955, either.)

Melloan’s stints as a Journal foreign correspondent and international affairs editor and columnist took him and his wife Joan, also a journalist, to Europe, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, and made him an expert on Soviet communism and the varieties of dictatorship under which countries in different parts of the world have suffered. His digest of news events, interspersed with analysis of U.S. foreign and defense policy, and U.S. economic and fiscal policy, is acute if a little meandering at times.

What stands out is his and his colleagues’ diligence in coming up with journalism’s “first draft of history,” along with his frank attempts to appraise where the newspaper’s editorial judgments were sound and where they weren’t. He admits he was too sanguine about the future of Russia in the hands of Boris Yeltsin, and about the spread of democracy around the world in the wake of communism’s collapse. On the other hand, in 1987, when the U.S. stock market crashed, he predicted that the crash would not have lasting ill-effects. It didn’t. A decade later he expressed confidence, contrary to the pessimism of his fellow anticommunists, that the British ceding of Hong Kong to China would not spell the end of Hong Kong as a vital center of capitalism. He was right about that, too.

Free People, Free Markets at several points becomes a tribute to the admirable human qualities and heavy intellectual firepower of Robert Bartley, who died in 2003. Bartley’s longtime deputy submits him to the same scrutiny to which he submits himself, writing that Bartley “proclaim[ed] a great victory for the supply-side revolution in the early 1990s,” only to be “blind-sided” by the Democratic win in the presidential election of 1992. In politics, “even when you think you’ve won, there are more battles to be fought.”