Lee Oser's Oregon Confetti and the Redemption of Portlandia

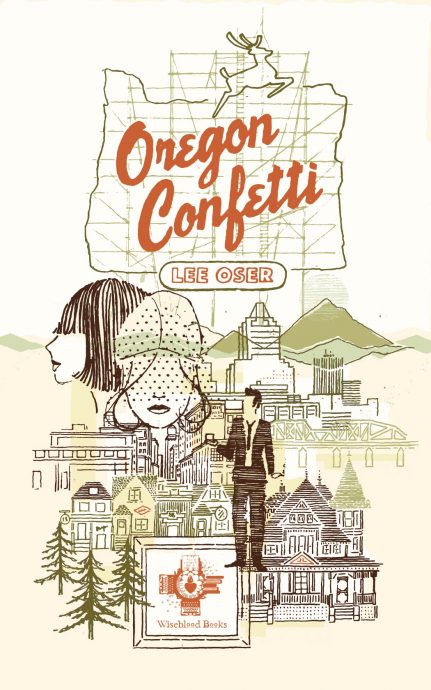

Law and Liberty’s featured author in this fourth installment of Conversations is the multi-talented Lee Oser, whose third novel, Oregon Confetti, has just been published by Wiseblood Books. The New York City-born Oser was educated at Reed College and Yale, and has been a professor of English at the College of the Holy Cross since 1998. He has penned several works of literary criticism, including The Ethics of Modernism (2007), and his two previous novels are Out of What Chaos (2007) and The Oracles Fell Silent (2014). L and L’s Associate Editor, Lauren Weiner, put questions to Oser about Oregon Confetti. Here is our Q and A.

Lauren Weiner: This is a novel heavy with literary references. The narrator, Devin Adams, gives us portions of The Thousand and One Nights, for example. He also gets embroiled in shady dealings in the art world, and so it’s a tale replete with forged documents, goons with guns, sex scenes, and lethal ambushes down by the pier. Could it be said that you’re defying the genre labels—or perhaps inventing a new genre, the bookish thriller?

Lee Oser: The way you describe it, Raymond Chandler comes to mind, for instance, The Long Goodbye. Samuel Beckett’s use of the detective genre is also relevant to what I do. His Molloy is one of the central books of the 20th century.

I am not so much defying labels or genres as trying to make use of them in whatever way I can. Everything I read is a means to this end. We don’t need Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize to remind us that we’re well past the point of narrow conceptions of “literary fiction.” Daniel Defoe wrote for his time, Leo Tolstoy wrote for his time, and there is a world of difference between them. When people talk about the literary novel today, usually they mean highbrow lyrical bloviating and political conformity of the most predictable kind.

LW: Many of our readers have seen or are aware of the well-done and influential television comedy Portlandia. Did that show make it easier or harder to write Oregon Confetti?

LO: I’ve seen Portlandia maybe a couple times. I like Fred Armison, and I’m delighted they made Kyle MacLachlan mayor. I’d vote for him in a heartbeat! But the show’s effect on me was basically nil. I had written about Portland in my first novel and I was going to write about it again. Maybe what I share with the show’s writers is a perception that Portland’s become a parody of itself. For them, the result is affectionate camp; for me, there’s the sting of loss. It’s still beautiful, Mount Hood and the Columbia River survive, but many native Portlanders feel the spirit of the place died a generation ago. By that I mean the particular richness of a local culture that had grown up over generations. Check out a Facebook page called “Dead Memories Portland” and read some of the comments.

My wife’s family comes from Oregon pioneer stock. Churches were important in Portland for a long time. Reed College and Lewis and Clark College had important chapels. Now it’s a land of weird spiritual fetishes, a region overrun by hordes of homeless people in desperate need of help, by grandstanding political types with a nasty flair for violence, and by expensive restaurants catering to an inbred class that grew up in California and New York. Some of the boutique economy is local, but not much else. I think intelligent people on the Left are starting to wonder what on earth happened. They instituted the laws and policies they wanted, but the cost has been high.

LW: The name of your publisher, Wiseblood Books, puts us in mind of Flannery O’Connor. Has O’Connor been an influence on you? What other authors have been?

LO: A guy named Joshua Hren started up the whole shebang and summoned authors and editors to his side. He is trying to keep alive a tradition of writing that is not necessarily closed to religious belief. You can’t get anywhere without these visionary types, and, as you might expect, he’s a lover of O’Connor. She was the last major American writer who happened to be a Catholic. Her famous criticism of the “average Catholic reader” speaks to the other side of the equation: Not only did she have to face the secularist mob, she had to face the Catholic mob as well.

I recall a recent conversation I had with a highly orthodox Catholic theologian. I had the honor of joining him for dinner when he gave a talk at Holy Cross, the Jesuit college where I teach. His talk was engaging and profound. But when he and I spoke briefly about James Joyce, I got the sense that he would discourage people from reading Joyce, despite recognizing his power as a writer.

Admittedly, it is a dangerous power. All worldly power is dangerous. But I hold that any writer worth his or her salt, of whatever creed or no creed, has got to work through Joyce. Likewise, the atheistic reader has got to work through Evelyn Waugh or Graham Greene or T.S. Eliot. Otherwise, you end up with double standards—one for your fellow religionists, and one for the world at large. It may be a strong temptation, especially in these days of political schism and the so-called Benedict Option. But it would amount to another form of provincialism, and we already have enough provincialism in this country, especially on the coasts.

With respect to novelists, I’ve always been drawn more to the dead than to the living. Top 13 in my list of gratitude (in no particular order): Charles Dickens, Waugh, Muriel Spark, John Kennedy Toole, J.R.R. Tolkien, G.K. Chesterton, Jonathan Swift, François Rabelais, Chandler, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Greene, O’Connor, Beckett. Never forget that O’Connor read Beckett. You have to read him, the language runs through him. Also, I have a special place in my heart for certain minor Catholic writers: Ronald Firbank, Myles Connolly, J. F. Powers (author of one of the most remarkable sex scenes in literature, by the way), and Piers Paul Read, who happily is still with us.

LW: Artists and entertainers loom large in your work. I think of Ted Pop, the egomaniacal rock star from The Oracles Fell Silent, and the painter John Sun here. What will readers glean about art, morality, and politics from Oregon Confetti?

LO: I would like to add theology to the list, if I may. Obviously sex is immensely important to our species and I think that we need theology to understand sex. In Western literature, Judeo-Christian thinking on sex has been elaborated, enriched, and sometimes contradicted by Platonism and by myth. I’m fine with that. But if you opt for a hygienic morality conforming to economic efficiency, the springs of passion are going to dry up. Intimacy disintegrates and the cash nexus fills the void. So I am trying to suggest that art, morality, politics, and theology are all closely connected, part of a larger picture, and that if we fail to see the connections between them, our civilization will shut down. There’ll be nothing left to sublimate.

Let me give one more example. Owning an art gallery, Devin [Oregon Confetti’s narrator] is nervously aware of how politics has corrupted the art world. My job as a writer was to show this process unfolding, through particular combinations of money and influence, as well as to detail the absurdities that result from it. The fact that the “hottest” art today is aimed like an expensive ad at the market (in one form or another), and that critical validation implies political validation, cannot be isolated from the rest of how we live. So I am trying to see the larger picture by means of recovering first principles.

LW: I went on a youtube tour of some of the New Wave music that you and your wife made in the 1980s. It was quite good. Have your ideas changed since then? Also, watching you made me wonder how composing and performing songs might compare to the writing of novels.

LO: My wife, Kate Lieuallen Oser, was such a groundbreaker on the Portland music scene. She used to hang out with Courtney Love and all kinds of interesting people. She was the most popular person in our band, The Riflebirds.

Probably writing songs for Kate’s voice helped me get into the frame of mind for writing fiction. As a novelist, you have to get other people’s voices into your head. You wear headphones in the studio, singing and hearing each other’s voices. Bands can be good that way.

As for my younger self, I was always resistant to cheap political fixes and stupid utopian rhetoric. I adore John Lennon, but “Imagine” is a dreadful embarrassment—like W.H. Auden’s poem, “Spain.” So I haven’t changed at all in that respect. But when I tried to write fiction back then—and I hacked away quite a bit—I simply lacked the experience in life, the raw material for any novelist. Also, like many young writers I was overwhelmed by modernism. Only in middle age did I gain the necessary perspective, so that I could work through the modernist crucible and arrive at a sense of what I could legitimately undertake. It took me a while to find my bearings as a novelist. A lot had to happen—deaths and children and teaching at a Jesuit college—but I still had energy to write.