Reviving the old meaning of "high crimes and misdemeanors" would allow judicial impeachment on prudential rather than narrowly criminal grounds.

Jacobin Writers Actually Agree with Madison on Democracy

Writing in the New York Times, Meagan Day and Bhaskar Sunkara, a writer and editor, respectively, of Jacobin argue the need for constitutional reform because “the subversion of democracy was the explicit intent of the Constitution’s framers.” Their evidence: James Madison’s observation in Federalist 10, partly quoted and partly paraphrased, that “‘Democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention,’ incompatible with the rights of property owners.”

The argument is an old one, and a common one, particularly among Progressives since at least the latter part of the 19th century. Setting aside the issue of whether Day and Sunkara’s proposals (including adoption of a unicameral national legislature and constitutional amendment by national referendum) would accomplish what they expect they would accomplish (surely a balanced budget amendment would be among the first constitutional amendment adopted if amending the Constitution were easier), their ham-handed reading of Madison’s argument in Federalist 10 disappoints. As well as the claim, seemingly meant to shock, that the Constitution’s framers were explicit about their intent to draft a Constitution that would “subvert democracy.”

As an initial, more-minor matter, I don’t think one can “subvert” something that doesn’t yet exist. I am unsure what measure of democracy would rank the democratic character of the national government under the Articles of Confederation higher than the democratic character of the national government under the Constitution.

More substantive to reading Madison’s argument in Federalist 10 honestly, to which we should all aspire regardless of we ultimately agree or disagree with the argument, is the bit of legerdemain Day and Sunkara play with the word “democracy” in their invocation of Madison’s claim. Indeed, Day and Sunkara manifestly include Madison’s ostensible alternative to “democracy” well within their own definition of democracy.

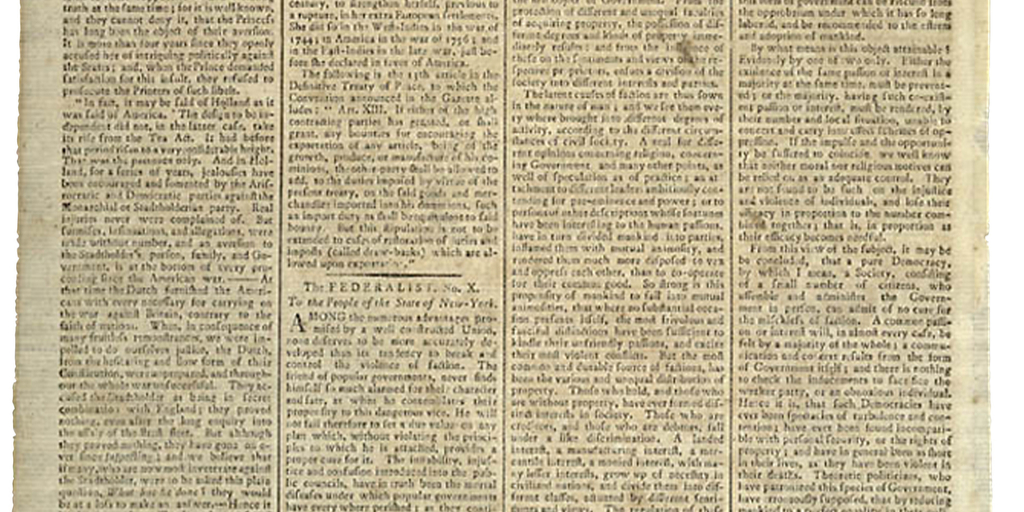

Madison himself defines his understanding of democracy in the very same paragraph Day and Sunkara quote:

From this view of the subject it may be concluded that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert result from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.

Madison’s alternative to pure democracy is not some form of authoritarianism, it is instead representative democracy, or republicanism. In the very next paragraph Madison writes,

A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure and the efficacy which it must derive from the Union.

The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

The thing is, we know that Day and Sunkara would fully characterize Madison’s “republic” as “democratic” because they themselves advocate as democratizing reforms, [1] a national legislature staffed by the people’s representatives (which, in Madison’s definition, is a republican institution but not democratic one) and [2] a national initiative, at least for constitutional amendments, as opposed to the small number of people that democracy requires in Madison’s account.

Even on Day and Sunkara’s grounds, what Madison discusses in these paragraphs – the section from which they lifted their own quotation, the very one that ostensibly incriminates Madison explicit intent to subvert democracy – falls well within their own conception of democracy.

Also disappointing is Day and Sunkara breaking apart Madison’s sentence in quoting it. Perhaps doing so makes Federalist 10 sound more sinister than it would without the edits. They partly quote and partly paraphrase Madison’s sentence this way: “‘Democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention,’ incompatible with the rights of property owners.’” Madison wrote, however, that democracies “have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property.” But quoting Madison’s concern about personal security dilutes presenting the Constitution’s framers as concerned only about property rather than people. Indeed, their concern for property was a good-faith concern for people, but that’s invites a broader discussion.

Publius purports to provide the reader with “an argument open to all.” Americans can and should feel free to take up the mantle and argue with Publius, the framers, and with each other over optimal constitutional design. The arguments themselves provide plenty of space for disagreement, even heated disagreement. There is no need to massage quotations to make the framers sound as though they meant something they do not in fact mean.