Flouting the Canon Law, Once More

Editor’s Note: This is part of a Law and Liberty Symposium on the crisis in the Catholic Church.

In the wake of the first great sex abuse crisis to consume the Catholic Church in America at the beginning of the millennium, much was made of the structural and legal reforms which could prevent such horrors from ever happening again.

The so-called Dallas Charter and the binding Essential Norms from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops were seen if not as a panacea, than at least as evidence of a clear-eyed assessment by the Church of what went wrong and what was needed to fix it.

Bodies like diocesan review boards, staffed by lay people, brought a measure of oversight to how allegations were handled, and the results as they can be measured so far have been encouraging: credible allegations of sexual abuse against clerics have dropped off considerably in over the last fifteen years.

The recent series of scandals to engulf the Church in the United States, first around Archbishop Theodore McCarrick and then following the publication of the Pennsylvania grand jury report, have left the hierarchy in a difficult position. On the one hand, the evidence seems to be that previous reforms are working, albeit with now obvious gaps in its applicability—most notably for addressing allegations made against bishops. On the other, the presence of so many unresolved cases, even if they are historical, in many dioceses suggests a continued reticence to go “looking for trouble” in one’s own filing cabinet.

As a response to the most recent crises, it is perhaps unsurprising that American bishops have been lining up to call for even more canonical reform, new process, and new structures. Independent investigations and a more “empowered” laity sound impressive and can produce a tangible outcome, be it new norms or bodies which can be produced.

The problem with this approach is that supposes that new reforms and norms are needed, and that they address a gap in the current canonical structure. There is, in fact, little evidence for this.

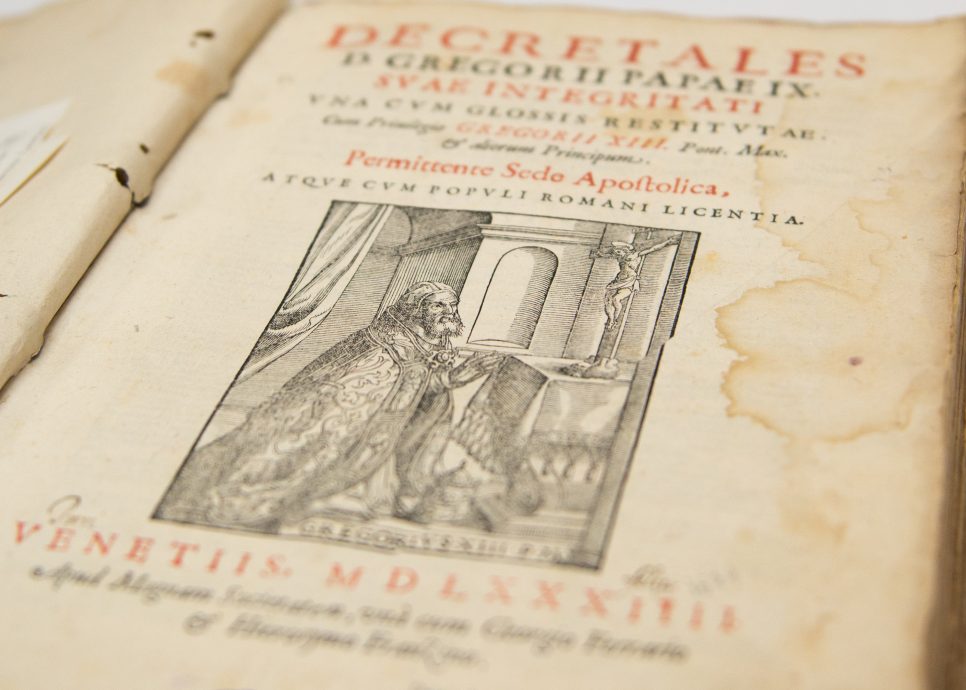

Contrary to what one might think looking at the USCCB’s Essential Norms, the pre-2002 Church was not a legal desert without a process for handling cases of sexual abuse. On the contrary, both the 1983 Code of Canon Law, and its 1917 predecessor, had clear laws and procedures for handling instances or allegations of sexual abuse by clergy. The trouble was that so many bishops treated these laws and procedures as optional, in many cases viewing the entire concept of “penal law” in the Church as an anachronism.

Instead of formally investigating allegations, filing charges where appropriate, and using proper canonical processes for sanctioning offenders, suspected or even confessed abusers were medicalized – sent for assessment and therapy before being “cured” and returned to ministry. This was done across dioceses in the second half of the twentieth century, and it flouted canon law in force at the time.

For all of the credit that the post-2002 Church in America received for its tough reforms in the direction of self-policing, arguably the most effective reform made in the wake of the first sexual abuse crisis was by Pope John Paul II who, in 2001, reserved all cases of sexual abuse involving clergy to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith – effectively taking the matter out of the hands of local bishops once the allegation was made.

Similarly, in the wake of the McCarrick scandal, much has been made of the apparent need for new processes to handle accusations made against bishops. Yet existing canon law is far from silent. As recently as 2016, Pope Francis created an entire new legal structure for accusing and formally trying bishops for a range of offenses, including negligence in handling allegations made in the diocese.

On paper, essential work of canonical reform has either been done already or was never actually necessary in the first place, at least in the sense that there were few if any true gaps in the law.

The real problem that must be addressed was highlighted by the USCCB’s National Review Board, which itself was created in the wake of the last abuse crisis to ensure expert lay involvement in the Church’s handling of sexual abuse cases at a national level.

In a statement released by the National Review Board on Aug. 28, they said that

the evil of the crimes that have been perpetrated reaching into the highest levels of the hierarchy will not be stemmed simply by the creation of new committees, policies, or procedures. What needs to happen is a genuine change in the Church’s culture, specifically among the bishops themselves.

As they point out, what the Church’s hierarchy has lacked over the last several decades is not the canonical mechanisms necessary for dealing with instances of abuse, but a zeal for justice and a willingness to apply the law. Addressing this lack requires a change of heart, or perhaps personnel, by the bishops of the United States, not a change of law.