Two American authors who used the grotesque to re-enchant the world.

Letters from Piety Hill

Every few years, some writer floats the prospect of a Russell Kirk revival, and with good reason. Whether watching in dismay as America’s “conservative” party launched one, and then another, war in the Middle East, or stepping back while the hacks of the conservative media take a club to every pretense of civilized refinement or prudent statesmanship, one cannot help but suspect that there must a better alternative on the Right, and that the place to go to try to discern its contours is Kirk’s august and copious volumes.

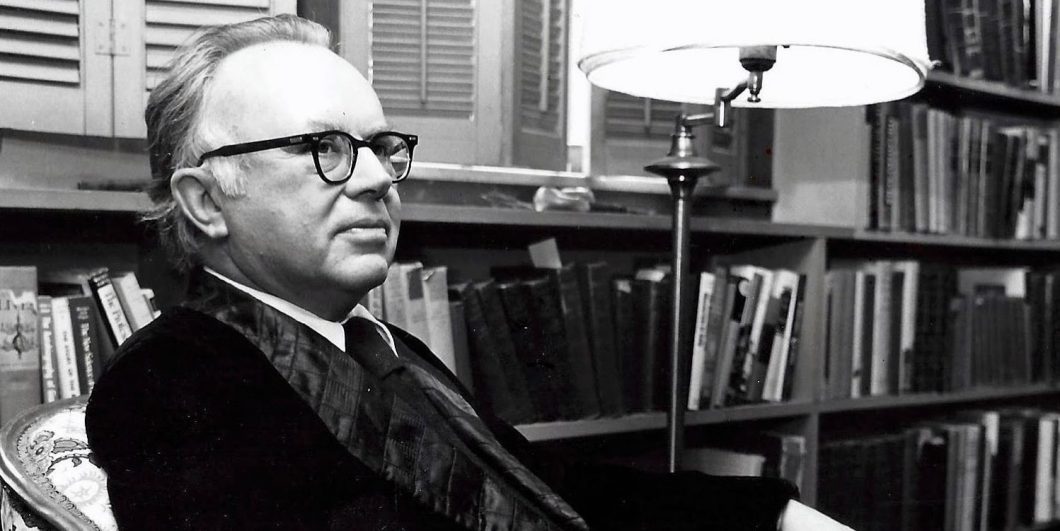

Our hopes were raised in 2015, with the publication of Bradley J. Birzer’s well-received Russell Kirk: American Conservative, and now comes a rich, entertaining, and often instructive selection of Kirk’s letters from James E. Person, Jr., a Kirk scholar who was also a Kirk friend and associate.

Anyone who has spent hours in the quiet of the Kirk library, down the street from his ancestral home, Piety Hill, in the central Michigan town of Mecosta, will have looked into one alcove at the heart of that building with both the fear and thrill of revelation. There, for decades, have been housed a thick archive of Kirk’s papers and personal letters. To sift through them in the making of Imaginative Conservatism: The Letters of Russell Kirk must have been an education in itself, for Kirk corresponded abundantly and generously with the great and the small, with scholars, statesmen, science-fiction writers, and also those merely curious about some question of Western civilization or the American Founding.

The volume Person has assembled nicely complements Birzer’s biography to deepen our encounter with Kirk (1918-1994) as man, father, philosopher, and author. It provides a fragmentary narrative of the progress of Kirk as a writer, and the ascent of conservatism as an intellectual and political force in American culture. It also suggests why Kirk was, in life as he remains in death, an eccentric figure, whose profound vision was at once venerably traditional and strikingly original, universal and yet peculiar.

He managed to deepen political and cultural thought in America, to bring profound ideas to the centers of political power and into the everyday language of political campaigns, even as he never quite fit in on the campaign trail and never stayed for long. He preferred to be typing away in the old cigarette roller factory he had transformed into a library in his ancestral village in the “wild backwoods of Michigan” (to quote one of his last letters), or travelling abroad, especially in his beloved Scotland. He was better suited, in other words, to the life of an independent man of letters than to the horserace of electoral politics. In consequence, there stands out a certain unworldly purity, an imaginative vitality not to say a rarified abstraction, in Kirk that appeals to us in sullied times. And there remains also a hope that such an imagination as Kirk’s may at least leaven our cultural and political life as it did the generations of the middle and late 20th century.

But now, as then, such a leavening is bound to be subtle and limited for reasons that admit of multiple explanations. Kirk’s thought, to be sure, offered a disposition, a sensibility, a way of imagining the world and living in it; it never proposed, nor could have, what he called, as the ironical title of an early book, A Program for Conservatives (1954). I want to give an account of that sensibility and its enduring appeal, and to suggest a very specific reason for its limitations, but not before providing some description of the delights Person has assembled in this volume.

Pagan, Stoic, and Christian

While the prose that Kirk wrote for publication was always rhythmic, allusive, and mannered, the letters we come upon here are often more workmanlike, concerned as they are with practical affairs in a practical tone. But some few of them stand nicely with his greatest passages, and indeed serve well as a summary of his position on such profound questions as religious knowledge. The handful of letters written to his wife and daughters, it must be added, are a testament of affection that would be worth the price of this book for themselves alone.

The letters from the 1940s show a young Kirk already fully formed in mind and outlook. Indeed, an essay he published in his teenage years (“Memento,” quotations from which can be found in Kirk’s autobiography, The Sword of Imagination, and in Birzer’s biography) shows his prose style and conservative vision already realized in a way that would be deepened and extended but never seriously changed in the subsequent five decades of his life. We see in one letter that his resistance to Christian faith, for instance, came not from youthful iconoclasm or rebellion, but from a pagan stoic sense that the zeal of Christian love could only eventuate in a sentimental leveling and egalitarianism that were repugnant to justice and good political order.

He sensed early that his love of old things was in the service of preserving and restoring order to the soul and the city, but what took him some time to discern were the contents of a tradition capable of doing this. He came upon it soon enough, and said as much in pitching to publisher Henry Regnery the manuscript that was to become The Conservative Mind:

It is my contribution to our endeavor to conserve the spiritual and intellectual and political tradition of our civilization; and if we are to rescue the modern mind, we must do it very soon. What Matthew Arnold called “an epoch of concentration” is impending, in any case. If we are to make that approaching era a time of enlightened conservatism, rather than an era of stagnant repression, we need to move with decision. The struggle will be decided in the minds of the rising generation—and within that generation, substantially by the minority who have the gift of reason.

Although Kirk only belatedly settled on a title for that 1953 book, it was the fitting one. His hope was not merely to depict, from the perspective of the historian, minds that had once been, but to make it possible for his readers to see and judge, to imagine, the world from within the spirit of Edmund Burke and T.S. Eliot. He wished to give unto others the conservative mind in which so many giants had shared.

Kirk’s conservatism offered, most obviously, an alternative view of the world to the radical ideologues of Marxism and also to the liberal or progressive utilitarians who had long dominated American politics—the totalists and neoterists, as he called them. But the most provocative aim of his work was to offer an alternative to the Old Right in America, whose most powerful figures were classical liberal or, more often, libertarian in outlook. William F. Buckley, Jr. had attempted to bring that Old Right Contrarian spirit into the mainstream with his book God and Man at Yale (1952), but that book’s recurrence to the word “individualism” to describe its author’s position would soon be swatted down by Kirk.

Kirk and the Intercollegiate Studies Institute

Libertarian individualism posed no challenge to the liberal or Marxist mindset, but merely played a variation on it. Kirk urged Buckley and the founders of the future Intercollegiate Studies Institute to recognize that the true source of resistance to those “totalist ideologues,” the Marxists of the modern American university, was to be found not in the defiant individual but in the “permanent things” of a civilizing and restraining tradition.

No one could put the case more crisply than Kirk himself—when he refused membership in the budding ISI. “I never call myself an individualist; and I wish that you people hadn’t clutched that dreary ideology to your bosom,” he wrote to ISI’s future president, Victor Milione, in 1954. Kirk went on:

Politically, it ends in anarchy; spiritually, it is a hideous solitude. I do not even call myself an “individual”: I hope I am a person . . . There are several great realities . . . in addition to the individual, and superior to him; and the greatest of them is God. As for your pantheon, if you choose Moses in place of Lao-Tsu, Aristotle in place of Zeno, Pascal in place of Spinoza, Falkland in place of Locke, Dante in place of Milton, Johnson in place of Smith, Ruskin in place of Mill, Burke in place of Paine, Adams in place of Jefferson, Stephen in place of Spencer, Hawthorne in place of Thoreau, Brownson in place of Emerson, you might succeed in capturing the imagination of the rising generation. You won’t otherwise.

Younger conservatives were moved to explore Kirk’s pantheon—his recommended reading, really—and so have many of us since, taking it as an invitation to enter a more splendid world (in a favorite phrase of his from Samuel Johnson) beyond the dreams of avarice. Kirk’s own early influences included libertarian Old Right thinkers—Albert J. Nock and Isabel Patterson—but he soon distanced himself from their thought in a way he rarely did with his other intellectual masters.

If that distancing was a sign of salutary growth, it came with consequences, too. The letters show Kirk’s awareness of how doggedly Frank Meyer and other libertarian thinkers within the burgeoning conservative “movement” of the 1950s sought to curtail his influence and frustrate his career. To them, Kirk’s conservatism was just a collectivism or authoritarianism of the Right. But did their opposition reveal that Kirk was right? Were they, at root, anarchists and solitaries who viewed the inheritance of the past as a hideous oppression?

Kirk stood no chance of defeating such thinkers in the offices of National Review, but he did fairly well at countering them in the long term. His interest was always more in the forming of the modern mind than in winning internecine battles within the conservative coteries or in influencing practical politics. From the 1960s on, the letters show him fending off attacks and seeking to overcome slights to maintain his standing in a world he had helped to shape. They also show him not simply resigned but content to make a living by way of his typewriter, and to carry on his scholar’s and “bohemian Tory’s” traveling life as much as time and money allowed.

His Prudential Vision

The letters also outline the kind of prudential political vision Kirk hoped would emerge from his writings. As is well known, he helped draft Senator Barry Goldwater (R-Ariz.) to run for President, and wrote two important Goldwater speeches, one of them magnificent, in the year leading up to the campaign. America resisted Soviet imperialism, Kirk’s words for Goldwater suggest, not because it defends the individual against the collective, but because man is a spiritual creature with a destiny to know and love the truth, not to sink into the complacent fat of material prosperity that satisfied capitalist or communist dreams. Man’s destiny is transcendent rather than immanent and good politics must be ordered thus.

Goldwater’s campaign failed, and Kirk was pushed out of the candidate’s inner circle before he could wield a more substantial formative influence, in any case. Kirk’s letters to Richard Nixon suggest that the 37th President had already formed himself into the image of the conservative statesman that Kirk had hoped to see lead the country. A note Kirk sent to a European friend speaks of his admiration for Nixon’s Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, and his great expectation that Nixon’s second term “will be distinctly conservative.” He further writes that he recommended T.S. Eliot’s Notes towards the Definition of Culture (1948) as presidential reading. We do not know if the advice to consult that hair-splitting and diffident slender volume by the great poet was taken, but we do know there never really was a second Nixon term, as it was overtaken by the Watergate scandal and the President’s resignation (regarding which Kirk wrote Nixon a letter of consolation).

Kirk had preferred the conservative statesman Nixon to the more individualistic Ronald Reagan, in the 1970s. But it is clear that, with Reagan’s election in 1980, his largely successful administration, George H.W. Bush’s election in 1988, and, not incidentally, the election of John Engler to the Governorship of Michigan, in 1990, Kirk believed the Republican Party would proceed to establish itself as a conservative party on principles first articulated in The Conservative Mind.

This was not to be. The end of the Cold War undermined the consensus among conservatives, who had largely been united by their opposition to communism. The elder President Bush’s swift intervention after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, leading the United States into the first Gulf War, replaced conservative opposition to communism with a general hawkishness that proposed to establish a “New World Order” and, eventually, a “New American Century.” This—unhappily—spared conservative politicians from having to conceive a principled platform outside the exceptional conditions of a threat emergency.

What might that platform have looked like? In the early 1990s, Kirk proposed six principles:

- Recognize the limits of institutional politics and counter cultural decadence and regain the “spiritual and moral object” in human life.

- Practice “salutary neglect of the domestic concerns of other nations.”

- Resist centralization and restore power to state and local governments.

- Encourage “small-scale and competitive enterprise.”

- Reverse the Great Society’s establishment of a permanent urban underclass, which was a “war upon the poor” that masqueraded as a war on poverty.

- Leave as much of social and political life as possible to “individuals and voluntary associations.”

Needless to say, these principles stand in stark contrast with the ideas of the post-Cold War Left; but neither do they fit comfortably within the Republican politics of the last two decades. To the extent any do, we have Kirk to thank. But, by 1992, he was sufficiently disillusioned by Bush’s pushing the country into war—“A war for an oil-can!” he called it—that he wound up campaigning, and campaigning hard, in support of that year’s Republican primary challenger, Patrick J. Buchanan.

Spirit of the Middle Provinces

Nearly all these letters were written from Kirk’s expansive demesne in Mecosta, Michigan, and that is not the least significant thing about them. His description of the conservative tradition was firmly rooted in the thought of Burke and the political tradition of Great Britain. It drew its principles, as his The Roots of American Order (1974) so magisterially demonstrates, from more ancient and extensive sources, however, the great cities of Western civilization: Jerusalem, first and foremost, Athens, Rome, London, and Philadelphia. In this sense, conservatism is the collective inheritance of mankind. But concerning the principles just enumerated—and the love of old, modest, and noble things that governed Kirk’s life—it must be said that their most obvious source was a tradition closer to home.

Kirk was, if not the last, then certainly the most influential, exponent of the Midwestern vision of American politics and culture. He was, as he so often noted, a true “Michiganian.” In his youth, it was Midwesterners who looked most askance at American adventures abroad, and who supported the anti-interventionist America First movement prior the Second World War. It was Midwestern regional writers and intellectuals who had long appreciated that the roots of every polity were fragile and precious goods only too easily shaken from the soil. It was the Midwestern spirit that, with the ancient Romans, recognized that civilization had been first established far away and that, therefore, the good citizen is the one who, with docility and piety, seeks to become civilized, by standing on the shoulders of giants or, better, by sitting at their feet and listening.

What Kirk really gave to American thought and to conservative politics, then—as the novelists Willa Cather and August Derleth would have recognized, and as the contemporary Midwest historian Jon K. Lauck has shown with great insight—what Kirk really gave to America, I say, was a vision of what our country would become if, and only if, it chose to receive the Western tradition according to the intellectual spirit and political tradition of its middle provinces.

Kirk’s conservatism was universal and ancient of days, but it was also a regional vision. It exercised considerable influence, but it also met with resistance from the expansive and moneyed establishment of the American northeast, the rugged libertarianism of the plains and far West (in his letters, he refers to the Kansan chemical engineer Fred Koch and his offspring with suspicion), and the perennially hawkish conservatism of the American South (for whose thought Kirk had great respect and sympathy but also reservation).

Only when we recognize this regional dimension of Kirk’s writings do we fully perceive how difficult, even impossible, it would have been for him completely to remold American conservatism. And yet, as a native son of Michigan myself, I will say that we would be better off if we heeded his words. Those who take time to relish Kirk’s beautiful letters to his intimates—his great expressions of romantic love and paternal affection—will likely agree. Whatever its imprecisions as a political platform, Kirk’s principles and way of life gave to him a wonderful character whose roots passed through Midwestern soil and on, as he first claimed in A Program for Conservatives, to the love that moves the sun and the other stars.