The Kantian dream of undoing real nations keeps foundering on the shoals of human nature's need for real attachments to place.

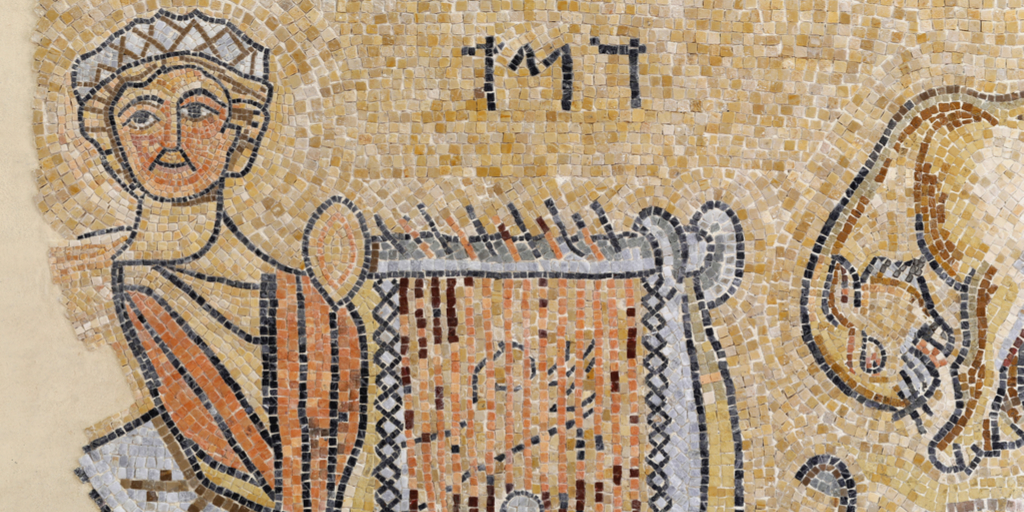

Universal Visions in the Old Testament

In The Virtue of Nationalism, Yoram Hazony argues,

The idea that the political order should be based on independent nations Twas an important feature of ancient Israelite thought as reflected in the Hebrew Bible (or “Old Testament”). And although Western civilization, for most of its history, has been dominated by dreams of universal empire, the presence of the Bible at the heart of this civilization has ensured that the idea of the self-determining, independent nation would be revived again and again.

He adds later,

For more than a thousand years, Christianity . . . aligned itself, not with the ideal of setting the nations free as had been proposed by the Israelite prophets, but with much the same aspiration that had given rise to imperial Egypt, Assyria, and Babylonia: the aspiration of establishing a universal empire of peace and prosperity.

Needless to say, it’s complicated. Nonetheless, I’d suggest that notions of Christian universalism—historically sometimes including a manifestly political dimension and other times not—exist in large part because of what the prophets and writers of the Old Testament taught, not in spite of it.

This starts almost at the very beginning of Israel, with the calling of Abraham (Abram, initially). Recall in the book of Genesis, the call of Abraham comes directly on the heels of the division of the nations by family group and language. Indeed, this division into separate nations is God’s judgment on an earlier united humanity that sought to pierce the firmament and storm God’s throne room.

While it is crucial to recognize that it is the ungodly aspirations of a united humanity that is judged at the tower of Babel, and so gives rise to separated nations as judgment, nonetheless, through Abraham, God immediately begins the long and difficult process of reconstituting and reuniting humanity under his kingship.

Poignantly, while the nations in Genesis 10 and 11 are united by blood and language, Abraham’s descendants, as Hazony notes, are not in fact defined by race. From the very start, the nation of Israel is an open classification: Circumcision, not blood, defines one’s relation to Abraham. One who is physically descended from Abraham yet not circumcised is “cut off” from Abraham’s people, while a foreigner who wishes to join with the nation, upon circumcision, becomes “as a native of the land.”

To be sure, the Abrahamic vocation—to bless the families of the earth—can be spiritualized, and often is, particularly in modernity. That it must be read as exclusively spiritual, however, is not manifestly obvious from the Old Testament writers and prophets. Hence my suggestion that notions of Christian empire derived as much, or more, from the imperial vision of the Old Testament Scriptures as they derived, as Hazony suggests they did, from the imperial aspirations of ancient Rome.

It’s not difficult to read an imperial theme throughout Old Testament Scriptures.

“But as for me, I have installed my king upon Zion, my holy mountain.” “I will surely tell of the decree of the LORD: He said to me, ‘You are my son, today I have begotten you. Ask of me, and I will sure give the nations as your inheritance, and the ends of the earth as your possession. You shall break them with a rod of iron, you shall shatter them like earthenware’” (Psalm 2.6-9, cf., Ps 72.8-11).

Or Psalm 72, in which, speaking of the human king of Israel, Solomon writes, “Let all kings bow down before him, all nations serve him (v. 11).

One need not wait until the creation of the Davidic kingdom to hear the message in the Old Testament. Abraham’s immediate descendants interpret his vocation in this fashion as well. When Isaac blesses Jacob (albeit thinking he was blessing Esau), he says, “May peoples serve you, and nations bow down to you” (Gn 27.29). And later, when Jacob blessing Judah, “The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff rom between his feet, until Shiloh comes, and to him shall be the obedience of the peoples” (Gn 49.10).

Later, then, speaking to Israel as a nation, Deuteronomy reports Moses proclaiming, “if only you listen obediently to the voice of the LORD your God, to observe carefully all this commandment which I am commanding you today. Of the LORD your God will bless you as he has promised you . . . and you will rule over many nations, but they will not rule over you” (Dt 15.5-7).

So, too, the prophets during the Exilic period: Isaiah proclaims “Kings will be your guardians, and their princesses your nurses. They will bow down to you with their faces to the earth and lick the dust of your feet” (Is 49.23). And Daniel, “And to him was given dominion, glory and a kingdom, that all the peoples, nations and men of every language might serve him” (Dan 7.11).

Mind you, all of this is the means by which the Bible describes the fulfillment of Abraham’s vocation to be a “blessing to all the families of the earth,” by reconstituting humanity and repealing the judgment at Babel. The result, ultimately, is universal peace, according to the writers and prophets.

I want to stress that none of the above suggests I think Hazony is wrong in his book’s larger argument, that human peace and wellbeing is better realized through a system of independent nation states than through a single world government. And I certainly do not suggest today’s secular internationalism can or does secure the universalistic aspirations of Biblical writers. Nonetheless, contrary to Hazony, we cannot really read a Westphalian-like system of nation states out of the Scriptures. The Scriptures provide a universalistic vision. Understanding the true nature of its universalism, not denying it, is the crucial issue.