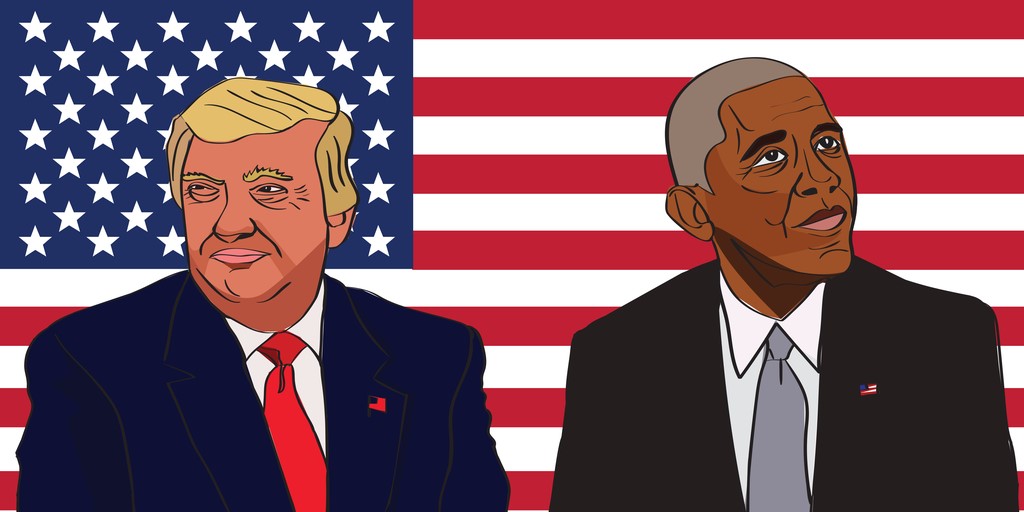

Obama and Trump: At What Point Has a President Forfeited the Public Trust?

A lot of Democrats are sure President Trump should be impeached. They just haven’t decided what the charges should be. Amazon still lists half a dozen books published from 2006 to 2008, advocating the impeachment of the second President Bush. A lot of critics said President Obama should be impeached (most, however, were content to vent that opinion online or on talk radio shows).

It’s true that the Constitution authorizes impeachment not only for “high crimes” but for “misdemeanors.” It’s not clear what kinds of acts the latter phrase was meant to cover. When the Senate was actually faced with its first impeachment trial—of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, in 1805—Chase’s defenders insisted that his partisan judgments and abusive jury instructions were no grounds for removal.

At the 1805 Senate trial, Luther Martin, the veteran of the Philadelphia Convention from Maryland, insisted that only an actual criminal offense would be proper grounds for removal. Conduct that was merely unseemly would be insufficient, said Martin. As Henry Adams later characterized him, Martin himself was “rough and coarse in manner and expression, verbose, often ungrammatical, commonly more or less drunk, passionate, vituperative, gross . . . ” The Marylander had started as an Anti-Federalist, then embraced the Federalist Party out of sheer loathing for Jeffersonian sanctimony.

Luther Martin was the sort of person Trump defenders might relish as their champion. But President Clinton’s defenders embraced Martin’s arguments, too. In 1998, all House Democrats and even some House Republicans accepted the argument of Clinton’s lawyers that mere abusive conduct in the Oval Office was not proper grounds for impeachment. Accordingly, the House rejected a proposed impeachment article for “abuse of power” and focused on charges involving perjury.

But the Framers were well aware that Britain’s Parliament had, in the 17th century and for centuries before that, used impeachment to address offenses we might now describe as malfeasance or betrayal of trust. Federalist 66 seems to say that the Senate would be justified in removing a President for “perverting the instructions or contravening the views of the Senate” in a foreign negotiation. And what the Clinton impeachment experience actually shows is that even a crime—Clinton’s lawyers did not deny that he was guilty of perjury—would not be enough, unless it were clear that the incumbent’s behavior had actually forfeited public trust.

So before Robert Mueller’s team has its say, we might do better to reflect on what we regard as unacceptable or untrustworthy presidential conduct. The immediately preceding administration offers the most obvious comparison. A recent book by Louis Fisher, President Obama: Constitutional Aspirations and Executive Actions (2018), is a good place to start. A useful companion volume in this exercise is an earlier book by my colleague at George Mason University, David E. Bernstein. Reviewed in these pages at the time (by Mark Pulliam), and featured on Liberty Law Talk, Lawless: The Obama Administration’s Unprecedented Assault on the Constitution and the Rule of Law (2015) is worth another look as an interesting counterpoint to the Fisher volume.

Abuses Pointed Out, But No Calls for Impeachment

Fisher is critical of Obama. He spent four decades working for the Library of Congress, most of it as an analyst for the Congressional Research Service, which provides legal and historical guidance for members of Congress. Indeed he maintains the restrained tone of CRS reports, even as he expresses continual warnings about executive overreach—as he has for decades.

Perhaps Fisher’s most clear-cut complaint is that Obama rewrote immigration law to protect unlawful child migrants and their parents and did so well beyond his own authority, as federal courts subsequently ruled. He also finds fault with Obama for indicating, when signing bills into law, that he reserved the right not to enforce some provisions. That practice had begun under Bush 43, with then-Senator Obama (D-Ill.) protesting it at the time. Similarly, President Obama is faulted for extending the Bush administration’s penchant for secrecy: he urged courts to respect a “state secrets” privilege that had, argues Fisher, at best a very tenuous legal basis. The Obama administration continued the Bush administration’s electronic surveillance of American citizens, and top Obama officials misrepresented the scale of the practice in sworn testimony to Congress.

Lawless discusses a number of abuses that the Fisher book fails to notice. Bernstein protests Obama’s use of leverage from federal bailout funds to replace the management of General Motors with Obama appointees and redirect investment to reward Obama constituencies or priorities. He protests reliance on “czars” who served in the White House without Senate confirmation but were still allowed to impose new policies, as Elizabeth Warren (before she became a U.S. senator) directed the establishment of the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Bernstein protests civil rights agencies’ running roughshod over free speech and religious freedom. As he reports, they were slapped down again and again for that by federal courts.

Yet some things that received a lot of attention at the time, at least among Republican critics, get almost no attention in either book. A Republican-led House of Representatives charged Attorney General Eric Holder with contempt of Congress for concealing evidence of abuse by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (involving the secret distribution of unlawful guns in Mexico). Obama’s Internal Revenue Service denied tax-exempt status to conservative advocacy groups on criteria not applied to others. Then there was Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s use of private computer servers to send and store email, including classified messages. It seemed important at the time it became known, but not to these authors. They also skip past President Obama’s continual rewriting of the Affordable Care Act, by which the President offered new exemptions and deferrals of obligation, as if the statute were his own personal project rather than binding law for the nation.

Neither Fisher nor Bernstein wrestles with whether Obama should have been a candidate for impeachment. But that’s the point. He was not (with a few exceptions) considered such by the media or the public. Of course, the mainstream media was anxious to protect President Obama, while they tend to be much more hostile toward and suspicious of his successor.

How Much of It Is Partisan?

But I draw some additional lessons from these books.

First, it’s hard to sustain the interest of ordinary citizens in an extended series of legal disputes about governmental conduct, especially when alleged misconduct does not entail distinct criminal offenses. The various charges tend to blur, and when that happens, the accumulation of details and examples undermines the force of any one accusation.

Second, it’s hard to compare one administration with its predecessors because a variety of distinct abuses don’t add up to a quantifiable aggregate of wrongdoing.

Finally, it’s hard to disentangle accusations from the larger context of partisan debate. Fisher, who takes cooperation between Congress and the President as the constitutional norm, criticizes President Obama for speaking dismissively of Republicans in his first years in office (when they were in the minority). The belittling made it that much harder to gain their support later on, when he needed it. But Fisher does not cite a single member of Obama’s Democratic Party urging restraint in real time, when it might have done some good—perhaps inhibiting Obama from saying, for example, that Republicans had “driven the car into the ditch and now ask for the keys back.”

It could be that Obama extended executive authority beyond reasonable bounds, and that he took partisanship too far. But Obama did not ridicule individual opponents. He never raised his voice. And he did not issue inflammatory tweets. President Trump—a “disrupter”—has asked to be judged differently from his predecessors. He will be, whether or not that ultimately provokes his removal from office.