Originalism is not merely a modern movement born in 1982; it is as old as the Constitution.

The Unenumerated Rights of the Privileges or Immunities Clause

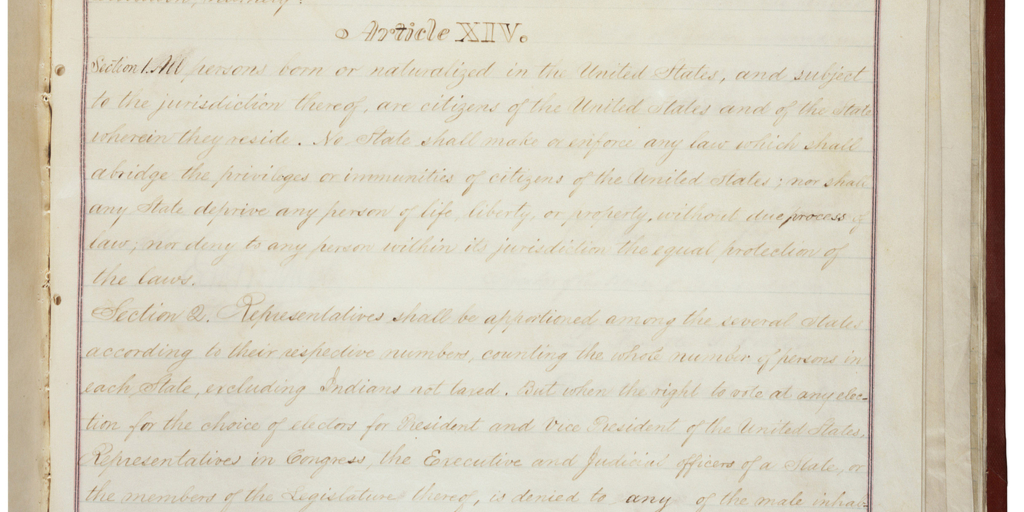

Does the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause include unenumerated rights, like the right to earn an honest living or make contracts? Professor Kurt Lash argued in a recent article that it does not. But that seems to be contradicted by the textual and historical foundation of the clause.

To understand the meaning of the Privileges or Immunities Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment, requires understanding the meaning of Article IV’s Privileges and Immunities Clause, which came first. We must start with the definition of each word according to the dictionaries of the era.[1] According to the relevant definitions in those dictionaries:

- “privilege” meant some particular advantage or right not universal

- “immunity” meant freedom (in a more universal sense).

In other words, a “privilege” refers to the positive rights granted by government to some individuals, while an “immunity” referred to the general or universal rights of freedom for individuals. Together, they meant all rights. This has been demonstrated in many other contemporaneous contexts by Eric Claeys.[2]

While Article IV’s Privileges and Immunities Clause is stated in the affirmative (of what citizens are entitled to) and the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause is stated in the negative (of what cannot be taken away), what’s significant is that other parts of the text are different.

The Privileges or Immunities Clause speaks of the right of “Citizens of each State” being entitled to the rights “in the several States.” The citizen of one state cannot be denied by another state the same rights that state recognizes for its own citizens.

Meanwhile, the Privileges or Immunities Clause protects the rights “of citizens of the United States.” A state cannot refuse to recognize the rights recognized by the federal government. If there is a right against the federal government’s power, that same protection is applied against the state’s power.

The historical context in which the Privileges or Immunities Clause was written is important as well. Specifically, there is a prior source for those words in the Articles of Confederation:

The free inhabitants of each of these states, paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice excepted, shall be entitled to all privileges or immunities of free citizens in the several states; and the people of each state shall have free ingress and regress to and from any other state, and shall enjoy therein all the privileges of trade and commerce, subject to the same duties, impositions and restrictions as the inhabitants thereof respectively.

Given this, we know at least one of the privileges or immunities referred to concerns “trade and commerce.” That was specifically cited as protected under the prior incarnation of this clause.

This clause was first substantially interpreted by Justice Bushrod Washington’s in Corfield v. Coryell (1823). It states those rights protected by the clause are those that:

are, in their nature, fundamental; which belong, of right, to the citizens of all free governments; and which have, at all times, been enjoyed by the citizens of the several states which compose this Union . . . [including] the following general heads: Protection by the government; the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the right to acquire and possess property of every kind, and to pursue and obtain happiness and safety.

To this Washington also added “the benefit of the writ of habeas corpus,” the rights to “maintaining actions of any kinds in the courts,” and to “take, hold and dispose of property, either real or personal.” Many of the rights referred to by Justice Washington are not enumerated in constitutions but are natural rights, such as the right to “enjoyment of life and liberty” in the Declaration of Independence.

Finally, a key context to understanding the Privileges or Immunities Clause is the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Many in Congress feared the law would not hold up in court without a constitutional amendment, so the Fourteenth Amendment was enacted to constitutionalize it. That law protected the right “to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens.” If we are speaking of privileges or immunities that were meant to be protected, this is a good list to start from, but the list also included natural rights not specifically enumerated in the Constitution.

It is true, as Lash states, that Rep. John Bingham and Sen. Jacob Howard, the respective floor managers for the House and Senate, made explicit the intent to apply the first eight amendments of the Constitution against the states. If they had merely stopped there, maybe the clause could be read to only apply to the enumerated rights, but they didn’t. For example, Sen. Howard specifically read on the floor of the Senate when debating this amendment a part of Justice Washington’s opinion in Corfield v. Coryell as some of the rights protected by the proposed clause. Sen. Howard’s speech included a variety of unenumerated natural rights such as the right to “protection by the Government, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the right to acquire and possess property of every kind, and to pursue and obtain happiness and safety.”

Sen. Howard then goes on to say it is “to these privileges and immunities, whatever they may be—for they are not and cannot be fully defined in their entire extent and precise nature—to these should be added the personal rights guaranteed and secured by the first eight amendments of the Constitution.” So clearly the clause must mean the first eight amendments plus something things that “are not and cannot be fully defined in their entire extent and precise nature,” i.e. unenumerated rights. This explanation comes directly from the lawmakers who proposed the amendment. The purpose, according to Sen. Howard, was to “restrain the power of the States and compel them at all times to respect these fundamental guaranties.”

And yet, Lash would protect the enumerated rights against state abridgement, but he would not protect the unenumerated immunities that the authors said were also protected by the clause. If the purpose is to restrain states and compel them to respect these rights, including those that “cannot be fully defined in their entire extent and precise nature,” then Lash’s interpretation cannot be the original meaning.

We know from the text, historical context, and legislative history that the clause included protection for unenumerated rights. From the text, according to contemporaneous dictionaries, we know the word “immunity” meant freedom in a universal sense. From the Articles of Confederation we know the unenumerated rights to trade and commerce were included. From the Civil Rights Act of 1866 we know the unenumerated rights to make and enforce contracts were included. And from the floor statements we know that all the rest of the unenumerated natural rights, including the right to the “enjoyment of life and liberty” in the Declaration of Independence, were specifically identified as within the rights protected by the clause. Perhaps a better constitution would be what Lash proposes, with less opportunity for mischief by judges who claim constitutional protection for rights which are not natural rights. But that is not the Constitution we have.

[1] John Ash, The New and Complete Dictionary of the English Language (1775); Thomas Dyche & William Pardon, A New General English Dictionary (13th eds., 1768), Samuel Johnson, A dictionary of the English language (4th ed., 1773).

[2] Eric R. Claeys, Blackstone’s Commentaries and the Privileges or Immunities of United States Citizens: A Modest Tribute to Professor Siegan, 45 San Diego L. REV. 777, 792 (2008).