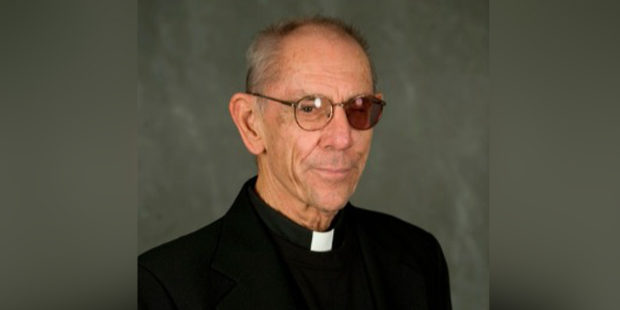

Fr. Schall's Final Rest

Being asked to write a brief tribute to Fr. James V. Schall, SJ (1928-2019) reminded me of a passage from G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy, one of Fr. Schall’s favorite books. If you asked an ordinary person why he preferred civilization to savagery, Chesterton wrote, “he would look wildly round at object after object, and would only be able to answer vaguely, ‘Why, there is that bookcase…and the coals in the coal-scuttle…and pianos…and policemen.’ The whole case for civilization is that the case for it is complex.” The case for Fr. Schall is complex. He is widely revered as a teacher, a scholar, a writer, a friend, an uncle, and a priest. He was a loyal son of St. Igantius Loyola.

Fr. Schall died on April 17, 2019. He was always keenly attentive to the significance of historical dates, and so I did some cursory research to see what other noteworthy events have taken place on April 17. Francis Cardinal George, another great American churchman and a friend of Fr. Schall’s, died that same day four years earlier. Pope Benedict XVI, so much admired by Fr. Schall, celebrated Mass at Nationals Park in Washington, DC on April 17, 2008. In the old Roman calendar of saints, it is the Feast of Pope St. Anicetus, celebrated as a martyr, and a fierce opponent of the Gnostic heresy. In homage to Fr. Schall’s pedagogical method, I sincerely hope that in the future professors who assign his books will open the class discussion by asking students, “When was Schall born? When did he die?” (No student who paid any attention in Fr. Schall’s classes could forget that Aristotle died in 322 BC. And if he did forget, Fr. Schall would ask again, and again.)

A great paradox of the life of Fr. Schall is that he was at one and the same time the most remarkable and yet most ordinary man one could hope to meet. The same man who had read his way through most of the Western canon, had seemingly considered the whole of political philosophy, had written over 30 books on diverse subjects, was also a man who loved a good football game and a beer and Peanuts cartoons.

In the 18 years that I knew Fr. Schall, I always marveled at the way in which he lived the virtue of charity and maintained so many friendships. Many people have properly observed that he had a genius for friendship. Book VIII of Aristotle’s Ethics was something he studied, taught, and practiced in equal measure. Study for Fr. Schall was never merely an abstract enterprise. It was always an important pursuit of what is. The purpose of the Christian life, and the essence of the Trinity, is friendship with God. The Incarnation made this possible in a previously unfathomable way, as Jesus told his disciples on Holy Thursday, “I have called you friends.” Fr. Schall noted in his last lecture at Georgetown, “The Final Gladness,” if we get friendship wrong, we will get everything wrong.

He once told me, drawing on Chesterton, I think, that all people are intrinsically interesting because they are all made in the image and likeness of God. If we don’t see what is interesting about the person in front of us, the fault is with us. Anyone who observed Fr. Schall over the course of a day could plainly see that in the way he treated every person who crossed his path. Charity, like friendship, was not only a lofty ideal or a theological concept. It was truly a way of life.

Fr. Schall loved quotations as much as he loved quizzing students on pivotal dates in history. The inscription on the façade of Copley Hall, the stately stone building in the middle of campus at Georgetown University, is a riff on Cicero. The inscription on Copley reads, “Moribus antiquis res stat Loyolaea virisque.” Roughly translated, it means “Loyola’s fortune still may hope to thrive, if men and mold like those of old survive.” Cicero borrowed the original quote from the Roman poet Ennius in Book V of De Re Publica. The allusion must have delighted Fr. Schall, who studied and taught Cicero for decades. Copley Hall is named for Fr. Thomas Copley, one of the first Jesuit missionaries to Maryland. During the English persecution of Catholics, he was arrested and deported to England in 1645, though he would later return to the colonies and died in Maryland. His burial place is unknown.

Fr. Schall walked past the inscription thousands of times in his decades at Georgetown. In his humility, I doubt it ever occurred to him that for those of us who looked to him for intellectual and spiritual guidance, he was that man in the mold of Ignatius, following in the faithful footsteps of Fr. Thomas Copley. One can hope that there will be men in their mold to continue that tradition.