Even laissez-faire policies need to be, at some point, engineered by some reformers.

A Legitimacy Crisis for Hong Kong—and China

Hong Kong has an illegitimate government and its illegitimacy underscores the substantial risk that China’s own government may become illegitimate as well. Illegitimacy, as I use the term here, is not a normative, but a positive concept. A government becomes illegitimate if enough of its citizens believe that its institutions are so fundamentally untrustworthy or unjust that the government cannot take controversial actions unless they are enforced at gunpoint. That is not true of legitimate governments, like that of the United States. They can retain the acquiescence of their citizens even if the great majority disagree with an important action that the government undertakes.

Hong Kong’s Legitimacy Crisis

Chinese policy has been a big factor in delegitimizing Hong Kong’s government. It has stopped movements for democratic reforms for the election of the Hong Kong’s chief executive, now chosen by small group heavily influenced by China, and of its legislature (“Legco”), now only partly directly elected. It has pressured Hong Kong to expel duly elected legislators who appear to oppose the sovereignty of China. It has kidnapped citizens of Hong Kong and spirited them off to the mainland for prosecution or torture, making the government of Hong Kong seem either powerless or complicit in gross violations of the rule of law.

These actions have helped create a crisis of legitimacy in Hong Kong. As a modern capitalist city-state nurtured by the United Kingdom, democracy and the rule of law have come to be seen there as the source of legitimacy. The median age of a Hong Kong citizen is 43. During his or her entire lifetime, that citizen has been connected to the West by both markets and media. Younger Hongkongers who have taken the lead in the recent protests are even more connected through the Internet and social media. They do not face the Great Firewall that inhibits people on the mainland from following current events or even learning the dreadful history of the Chinese Communist Party.

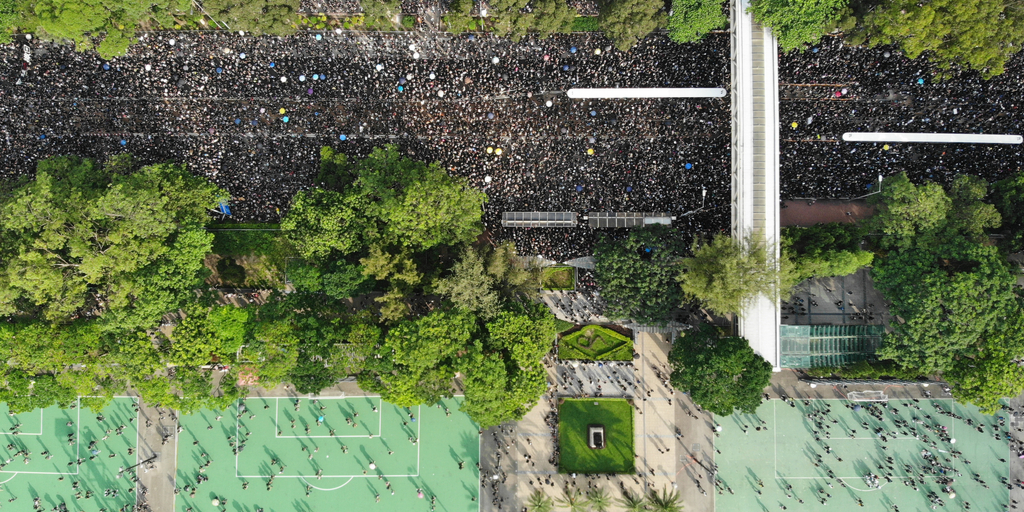

Thus, it was hardly a surprise (although it seemed to come as one to Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s hapless chief executive), that legalizing extradition with China even along with other nations would create a flashpoint for unrest. Hong Kong had inherited an independent judiciary from the United Kingdom that continued in force after sovereignty was transferred. China’s legal system, however, is controlled by the Communist Party. Over a million people (or one in every seven Hongkongers) joined mass protests against it. When these protests did not seem to succeed in getting the bill withdrawn, young people surrounded the Legco’s building and prevented the legislature from meeting.

And when an illegitimate government tries to take controversial action and fails, it further weakens its power. This dynamic is playing out in Hong Kong. While Mrs. Lam has announced the suspension of the extradition bill, even larger mass demonstrations demanded that the bill be pulled from consideration permanently, that she apologize for the actions of the police during the prior demonstration, and that she resign.

The repercussions of this failure will be felt in Hong Kong for years to come. The government is likely to be further weakened in the medium to long term by losing its pro-mainland majority in the legislature. Currently, the government has a relatively narrow majority that depends on greater support in functional constituencies that are more insulated from the popular will than those elected by ward. These former constituencies largely consist of people from select professions, like lawyers, accountants, and various lines of commerce, and of labor union members. As the young become a greater proportion of these constituencies, however, they cannot be counted upon to vote for pro-mainland parties. And even now, I suspect that many such legislators were reluctant to ultimately push for the extradition bill, because doing so would bring severe social repercussions from their associates, friends, and family.

These developments will then create greater problems for the mainland. The restoration of Chinese sovereignty over Hong Kong was once a source of national pride and legitimacy. But now its example might become a democratic virus, literally a metro ride away from parts of the mother country.

China’s Legitimacy Dilemma

The threat is particularly acute because the legitimacy of the Chinese government is hardly assured. The CCP has a tenuous hold on legitimacy in light of what it wrought in the last century—a totalitarian state, a famine that killed 20 million people, and a “cultural revolution” that killed hundreds of thousands more as well as upending millions of lives. The U.S. press focuses on the legacy of Tiananmen Square. But demonstrations against the Chinese government’s action in 1989 necessarily reflect discontent with the party itself for its history of outrages, of which Tiananmen is only one of the most recent large-scale atrocities. (Another is the creation of “reeducation camps” for citizens of Uighur descent, who have committed the “crime” of adhering to their Muslim religion.)

And the Party cannot apologize for Tiananmen, for that expression of remorse would obviously raise the question of why it should not apologize for its even more destructive acts. And once it takes responsibility for vast evil, why should anyone regard it as the legitimate ruler of China?

China had an implicit answer to that question in the era of Deng Xiaoping and for years afterwards. The CCP was then delivering tremendous economic growth, lifting people out of dire poverty even if it made tremendous mistakes in the past. The implicit bargain the Party offered was that, if the public would forget the past, it would deliver a decent present and an even more glorious future. But that bargain has frayed over time. First, new generations unfamiliar with the privations of Maoism take economic growth for granted. Second, the propertied begin to be worried about how to protect their property against arbitrary decisions. This concern drove political change in the West, as the middle class demanded more democracy and a better rule of law to protect itself. Finally, the more prosperous China becomes, the harder it is to prevent Chinese citizens from being connected through travel, education, and other means to the rest of the developed world, where democracy and the rule of law are thought to be the central legitimizing principles.

The rise of Xi Jingping has to be seen against the ever-present potential crisis of legitimacy. His government is trying to revive the old slogans of communism along with nationalist sentiment to provide a basis for legitimacy deeper than the prosperity bargain. Moreover, Xi’s strongman leadership, very different from the consensus politics of the last three decades, creates the potential for a cult of personality, which can also offer the regime a form of legitimacy. Centralized power prevents the kind of factional disagreements that make it harder for the Party to keep coherent its propaganda message on its continuing legitimacy.

Understood in this way, Xi’s accession shows the fragility of the communist regime. It is risking more concentrated power to preserve legitimacy. And yet concentrated power is more likely to lead to mistakes of the kind that have been made in Hong Kong, and such mistakes undermine the regime.

Of course, China is all the more dangerous because its legitimacy is fragile. In the face of mistakes and setbacks, aggression against enemies is one way to unite a nation, at least temporarily. That is why the events in one city over the course of a few weeks likely have global repercussions for years to come.