A clear-eyed understanding of the threat China poses to the United States is genuinely frightening.

What Are the Engines of Progress?

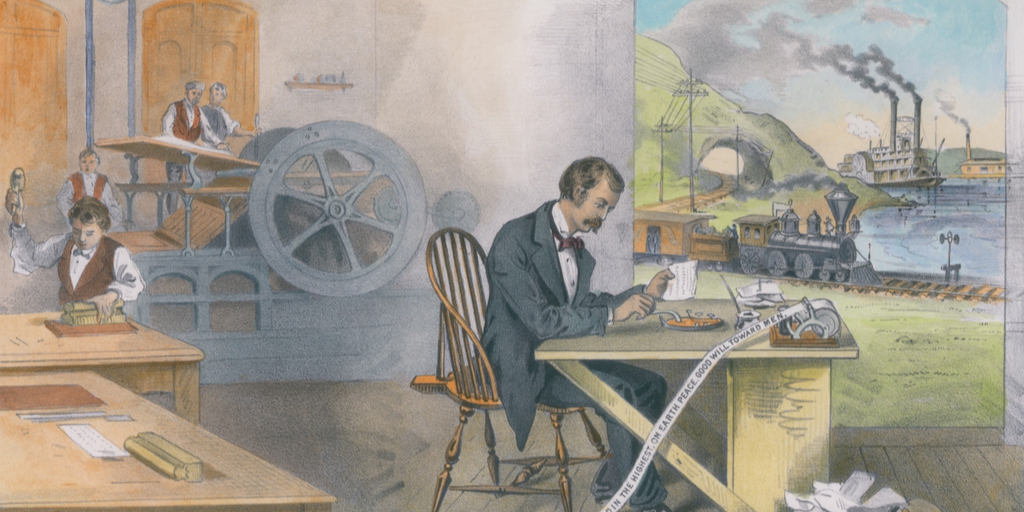

Writing two novels about how the industrial revolution may have looked had it taken place in a different civilization — pagan Rome rather than 18th and 19th century Britain — means I now get to review books by real historians on what they think goes into the secret sauce of economic growth and human development.

Stephen Davies’s The Wealth Explosion: the Nature and Origins of Modernity and Douglas Carswell’s Progress vs Parasites: A brief history of the conflict that’s shaped our world set out to explain why we have dentistry and people in the past did not. “In general, life is better than it ever has been,” P. J. O’Rourke wrote in All the Trouble in the World. “If you think that, in the past, there was some golden age of pleasure and plenty to which you would, if you were able, transport yourself, let me say one single word: dentistry.”

O’Rourke’s “dentistry” is of course a proxy for many things. Before Davies and Carswell start talking about Chinese dynasties and Scottish philosophers and enlightened doges, they make two related points. First, the way we live now — roughly, the last 250 years — really is different from everything that went before. Secondly, that difference has particular characteristics. Both men set out their case contrarily from Steven Pinker (who makes a similar argument at book length in The Better Angels of our Nature), partly because Davies is an historian and Carswell is a politician while Pinker is a scientist. For Davies, this means there are no graphs or diagrams, but an abundance of what Australians call “ripping yarns”. Given many people are unmoved by graphs but are moved by narrative, it’s possible The Wealth Explosion will persuade where Better Angels did not. Carswell, meanwhile, is razor-sharp in his descriptions of the way political elites predate on their populations unless their power is dispersed among multiple institutions and office-bearers.

Materially, modernity means there are more of us, largely because four in ten children no longer die before puberty. That vast population lives uncommonly well while the proportion of the world’s people living in what the World Bank calls “absolute poverty” is dropping like a stone and has been for decades. Our economies are overwhelmingly powered by intensive growth — that is, growth arising from inputs being used more productively. Before the 18th century, nearly all economic growth was extensive, which made the quantity of output produced dependent on expansion of the quantity of inputs used. Whence things like colonialism and brigandage.

Most of us now live in cities, something that emerged only as recently as 1851, when the “census revealed that for the first time in human history (…) a majority of the British population lived in towns with a population of more than fifty thousand”. Incredible as it may seem in light of the ongoing Brexit mess, governments in modern liberal democracies are also astonishingly competent. The most able Roman prefect or Chinese mandarin — placed in a time machine and deposited in Whitehall — would be stunned at the lack of corruption, how we’ve succeeded in abolishing the sale of public offices, and our genuine concern for what Davies calls “the general welfare”. Carswell describes how governments — with relatively few exceptions — were historically extractive super-predators. And even those that did not aspire to be extractive super-predators (Rome and China for significant parts of their history) were nonetheless riddled with corruption and pervasive clientelism.

We are also morally different from our ancestors, and that includes the most enlightened and high-minded of them. People across the political spectrum are concerned about harms to unrelated strangers in distant lands, while across the developed world and large parts of the wealthier developing world, men and women are legal and political equals. These moral changes are simply extraordinary in light of what went before, something Davies in particular details with élan precisely because of his gift for storytelling.

Once they’ve cleared the statistical undergrowth, both then discuss why historical civilizations that looked like they were about to make like Manchester in the 19th century somehow didn’t. It’s at that juncture the two books diverge. In part this is due to a difference in background. Carswell, the historian-turned-politician, pays more attention to the behavior of members of his former profession (he was an MP for 12 years). Davies is an academic historian, which tends to give him both a longer and more melancholy view.

Some of those civilizations were extraordinary, too — Republican Rome, Song China, Venice’s Serene Republic. All three looked for a time like they would achieve what the Netherlands and the United Kingdom achieved between the 17th and 19th century: industrialization followed by what Davies calls “modernity” and Carswell calls “progress”. Why they didn’t is part of both books, but why the UK in particular did forms much of the rest.

Because both books are short, their authors are forced to provide detail on only one or two case studies, but this has happy consequences. Davies’s chosen focus is Song Dynasty China (960-1279), which encourages UK and American readers to take a much-needed interest in Chinese history and captures the extent to which (now) modern, wealthy China appears to be producing a different kind of industrial modernity from that birthed in 18th century Europe:

Although systematic innovation was limited and hampered in all pre-modern societies and civilisations, this was less true in China than elsewhere for a very long time. The list of major innovations that were first made in China is a very long one and includes such things as paper, porcelain, gunpowder, the blast furnace, the wheelbarrow, and a civil service recruited on something like merit. China’s lead in this respect lasted until the fourteenth century but it then ceased.

Carswell, by contrast, focuses on the Roman Republic and, only a little more briefly, the Serene Republic of Venice (“Serenìsima Repùblica Vèneta”). Both are familiar to British people if not to Americans thanks to decades of cheap foreign holidays on the Continent:

During the late Republic, a factory system in Italy was producing pottery, arms, bricks, pipes, tiles, and even textiles. Significantly, they were producing for a mass market, not just individual or local consumers. There was a standardized, mass-produced oil lamp, and red slip pottery. Wool weavers in small factories were selling to distant markets.

Roman law allowed bottomry loans – a kind of conditional loan whereby an investor funded a sea voyage on the understanding that if successful, they were entitled to a certain share of the profits. If, on the other hand, the ship was lost, those that had invested in the scheme would only have limited liability for losses. This encouraged investment.

Song rulers, meanwhile, did things like abolishing internal passports (a version of the Hukou system has existed for most of China’s history, making this a major policy shift); allowing a genuine free market in land (including the crucial right to alienate); ending the payment of taxes in kind or by corvée labor and preferring money instead; constructing navigable canals to facilitate internal trade, and building a huge merchant navy. Song China began to enjoy modern-style intensive growth: agricultural output doubled over the period 960-1279, an extraordinary achievement in a society without modern fertilizer and the scientific interventions of Norman Borlaug.

What undid the Song? Why wasn’t the Industrial Revolution Chinese rather than British? As is always the case when historians examine “root causes”, Davies’s explanations blend external shocks with domestic government policy. The Black Death was a major factor, scything down nearly 90 per cent of China’s population in some regions before it made its way along the Silk Road to wipe out half of Europe. Shortly thereafter came the Mongols, who scythed down anyone left standing and sacked Baghdad — the leading center of Islamic civilization at the time — while they were at it.

Crucially, the Mongol victory over Song China’s largely Han population inflicted a form of psychic harm on the country. Long after China threw the Mongols out and re-conquered vast amounts of territory, Song Dynasty policies were associated in the Chinese national imagination with weakness and defeat. Subsequent dynasties set about reversing every single one of them, sometimes in extraordinarily stupid and destructive ways. Peasants lost the right to sell their land, internal passports were re-introduced, and the immense ocean-going junks of the merchant marine (called “Treasure Ships”) were deliberately destroyed.

What undid the Romans? Why wasn’t the Industrial Revolution Roman rather than British? After all, they too had begun to enjoy intensive growth. Carswell is narrower in his focus than Davies. He points to the concentration of political power in fewer and fewer hands, and to widespread adoption of religious beliefs that posited a world of divine, top-down order rather than spontaneous or emergent order from below. He is not particularly kind to either late paganism or early Christianity:

For the next thirteen centuries, what had been Roman Europe was preyed upon by parasites who organized society for their own intent and purpose. A Dark Age lasted for centuries, with society reverting back to subsistence level as parasitic warlords extracted what they could from the productive.

The parasites have waged a long war against the idea of order as an emergent phenomenon. They not only largely extinguished Lucretius’s ideas in the first and second century, but they burnt the Italian monk, Giordano Bruno, in the sixteenth century, and Spinoza’s books in the seventeenth century. They were still fuming over Darwin in the nineteenth.

He suggests Christian and Islamic theological “order from above” reasoning was of a nastier sort than that in Roman paganism or Taoism, or even in Confucianism. Modern people tend to associate Confucianism with filial piety and Chinese cultural collectivism, forgetting that the Chinese Emperor could “lose the Mandate of Heaven”. This framework functioned rather like the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, which meant the Scots could sack their king.

In the process, he observes drily that the Roman world’s Hayek-cum-Darwin — the philosopher-poet Lucretius’s De rerum natura — only survives in a single manuscript. He then makes an explicit link between Lucretius’s ideas about emergent order — and their popularity among many Romans — to what is called “the knowledge problem” in economics. His account reminds me of how, some time before 1989, a Soviet official asked economist Paul Seabright who was in charge of London’s bread supply. Seabright gave an answer that is comical but true: “nobody”.

In a sense, Carswell is setting Christianity’s development of the moral equality of persons against Lucretius’s development of emergent order and finding the former wanting. Moral equality, in Carswell’s vision, is no good to us if we’re all equally sleeping under bridges, begging in the streets, and stealing loaves of bread. This is the first time I have seen an argument traditionally used against fiscal conservatives used against what has become a key tenet of socialism. It does mean, however, that Carswell the passionate democrat and Brexiteer is often forced to praise what he calls “open oligarchies” and take a position that echoes Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht: “first meat, then morality”. For Carswell, economic prosperity has independent moral value that trumps key moral claims from other traditions when those moral claims are coeval with grinding poverty. There is a part of me that would like him to debate lawyer Steven Smith on this point. In Pagans & Christians in the City, Smith – better than any author I’ve read previously – balances the moral claims of classical paganism and emergent Christianity against each other.

What, then — come the 18th century — made North-Western Europe, and especially the UK, different? Here Davies scotches many of the “European exceptionalism” arguments (everything from an average older age at marriage for women to the presence of large numbers of animals suitable for domestication to the independent Roman and English development of the rule of law) and focuses instead on the extent to which Europe never became become a “Gunpowder Empire”, despite concerted attempts by the Hapsburgs to make it one (“the Holy Roman Empire was neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire”). Every other relatively developed region in the world in the same period — from Russia to the Ottomans to China to Safavid Iran — did. For his part, Carswell pays respectful notice to Daron Acemoğlu and James A. Robinson’s “inclusive institutions” argument in Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty but argues it’s the ethical and religious ideas underlying institutional formation that determine whether they will be extractive or inclusive.

Both discuss the extent to which Europe — and especially Western Europe — became a system of states. No regional hegemon emerged, and the only way for the European powers to keep pace with competitors after the crucially important Peace of Westphalia in 1648 was to innovate. Failure to innovate meant the country next door eating one’s national lunch. Even if a given ruler didn’t particularly like capital markets and science (they had a nasty habit of blowing holes in organized religion, which European rulers used to unify their respective countries), he or she was forced not only to allow but to encourage them. The price otherwise was being shoved definitively to the back of the military queue.

“Modernity” thus took on a European — and especially British — cast. Carswell in particular, but also Davies to a degree, note the extent to which the UK already had strong institutions of governance independent of the Crown (Parliament and the Courts). This meant, because it was first to break away from the peloton (most European states remained absolute monarchies), liberal democracy and market capitalism were twinned in the minds of many observers. For decades, the claim that one implied the other was treated as a species of historical inevitability, a phenomenon that came to be known as “Whig History”. Here once again both Davies and Carswell depart from what is a common (and newly re-popular thanks to Steven Pinker’s efforts) account.

Davies points out that while modernity is indeed special and we’ve only had it for a short time, it is pure historical contingency it looks British. It could have looked pagan Roman, or Venetian, or Chinese. It may still come to look Chinese for the simple reason that China has been in pole position as a civilization for much of world history. Davies’s vision is in that sense deeply melancholy. Great economic prosperity, he suggests, requires “permissionless innovation” but does not require many of the other things we associate with modernity — not even the abolition of slavery or other vicious systems of social control. Societies where women weren’t considered chattel and generally had significant rights (pagan Rome and medieval Japan are the two stand-outs) nonetheless found another large group of people to treat appallingly for reasons we moderns find thoroughly obnoxious, for example. China’s behavior towards the Uighurs and in Hong Kong indicates authoritarian capitalism will be a terrifying rival to liberal democratic capitalism for decades to come.

Carswell, by contrast, holds out more hope for the future interdependence of economic freedom and civil liberties. The emergence of a personality cult around President-for-Life Xi Jinping coincided with a rash of arbitrary rule-making directed at Chinese “national champions” like Ten Cent and Ali Baba. This sort of rule could kill the goose currently laying China’s economic golden egg, as restrictions on civil liberties and political concentrations of power typically undermine economic performance. He is nonetheless far more circumspect in his claims about such a link than Francis Fukuyama, who wrote shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Carswell’s view of slavery is more in line with conventional scholarship. He describes it as “the ultimate extractive institution”, noting that within forty years of abolition, the US economy was the largest on the planet. He joins the majority of economic historians in arguing that slave labor is comparatively unproductive and undermines intensive economic growth — one reason why slavery’s strongest opponents were often ardent advocates for capitalism and free trade.

Who is right, Carswell or Davies? What are the engines of progress? My suspicion is that one doesn’t get permissionless innovation unless the dispersal of power among elites constrains their tendency to predate on the productive. Maybe I’m simply splitting the difference between two compelling arguments, but I did come away thinking both authors are half-right. I also think there is something to be said against religious (and, later, rationalist) traditions that suggest entire civilisations and the natural environment can be ordered from above by a single mind. The twin claims of omniscience and omnipotence always struck me as frightfully Soviet, a divine form of central planning.

Finally, both The Wealth Explosion and Progress vs Parasites gave me a strong sense that, if development is to remain about more than dentistry and material comfort, those of us committed to liberty and individual autonomy need to make our case better than we have done of late. These two books make it unusually well.