NPR's new ethical guidelines for its journalists could benefit from centuries of natural law tradition.

The Ongoing Decline of The New York Times

I have been reading the New York Times for over five decades. By the time I was ten, I came home from school to immerse myself in its pages, enthralled as the outside world enveloped me each evening at my parents’ kitchen table. I even played the game Stratego on the porch of our country home against an older boy who would become its publisher.

It is thus painful for me to watch the fall of a once-worthy institution. At one time, it had some claim to be the United States’ paper of record because of its objective reporting and the absence of a persistent agenda in determining what news was fit to print. A sensible center-left perspective generally drove its editorials. These were not my views then or now, but the paper offered a useful challenge to my enduringly classical liberal perspective.

In the last decade, however, editorials have moved sharply to the left to the point of abandoning economic rationality. For example, while the Times has consistently favored higher taxes, it once recognized that interference with the market could be counterproductive and thus did not support expanded rent control in New York. But now it is a vocal cheerleader for the policy, one that economists, right and left, believe undermines cities’ housing stock. Its editorial page inveighs against climate change denialists while becoming a denialist of fundamental economic laws.

The op-ed page began as something of a counterpoint to the editorial board. Now, the op-eds are almost uniformly left leaning and the op-ed editors appear to be interested in further slanting the submissions they receive. One recent op-ed, for instance, summarizing two reporters’ finding about the Kavanaugh nomination controversy, was edited to omit the important fact that another woman who Kavanaugh was said to have exposed himself to at Yale did not remember the incident. Their new motto seems to be: “don’t print the exculpatory facts about disfavored public figures.”

More troubling is the bias on the news pages. To be sure, our democracy has survived periods where one could only find highly partisan sources of news. Lest we embrace nostalgia, we should remember that papers in the early republic were almost uniformly cheerleaders for one party or the other. But in an era where public policy is more complex because the government does so many more things, a common set of facts promotes good policy and tamps down on polarization.

While as a long-time reader I can only offer my general impression of increased bias, others have tried to catalog it. In Reason, John Stossel considered flagrant bias in headlines, like the ridiculous assertion that terminating net neutrality will kill the internet. Even a former managing editor, Jill Abramson, herself recognized that news pages have become biased where Trump is concerned. A recent example is the almost comical attempt to prevent the President from bolstering his standing after the elimination of the terrorist Baghdadi by suggesting that he almost prevented the raid from happening.

The editors further display their bias not only in what they do publish, but also in what they choose not to publish. The Sunday Business section, for instance, features very few stories on the innovations of important businesses in America. Instead, the section, which appears to be shrinking, looks more at how social issues that the editors deem important interact with business and thus provides an opportunity to criticize corporations for being insufficiently socially responsive. It is a business roundup for people who emphatically do not think that the business of America is central to America’s greatness.

Beyond specific instances of reporting bias, the Times recently decided to promote an entire counter-narrative about American history—the 1619 Project, an attempt to see all of American history through the prism of slavery. It thus has left news reporting—something its editors are equipped to judge—and decided to usurp the function of professional historians. The results are absurdly presentist, skewing history to undergird the editors’ political imperatives. For instance, the introduction to that series makes the extraordinary claim that a prime motivation for the American Revolution was the colonists’ fear that Britain would abolish slavery. As one distinguished historian of the revolution told me, the problem with this proposition is that there is no evidence for it.

The Times has also taken to interspersing its obituaries with historical accounts of women and minorities who died in the long past but that its editors believe should have had obituaries. It may be that some of them would have been memorialized under current standards, but the editors are journalists, not historians, and surely significant people who did not get obituaries are not limited to those of particular races or a gender. This series is an exercise in virtue signaling, not reporting. And, like the 1619 Project, it shows that even outside its editorial pages the Times is interested in pursuing claims about what it regards as justice and will not simply stick to the difficult enterprise of finding the facts of our contemporary world.

There are three explanations for the Times‘ decline, not mutually exclusive.

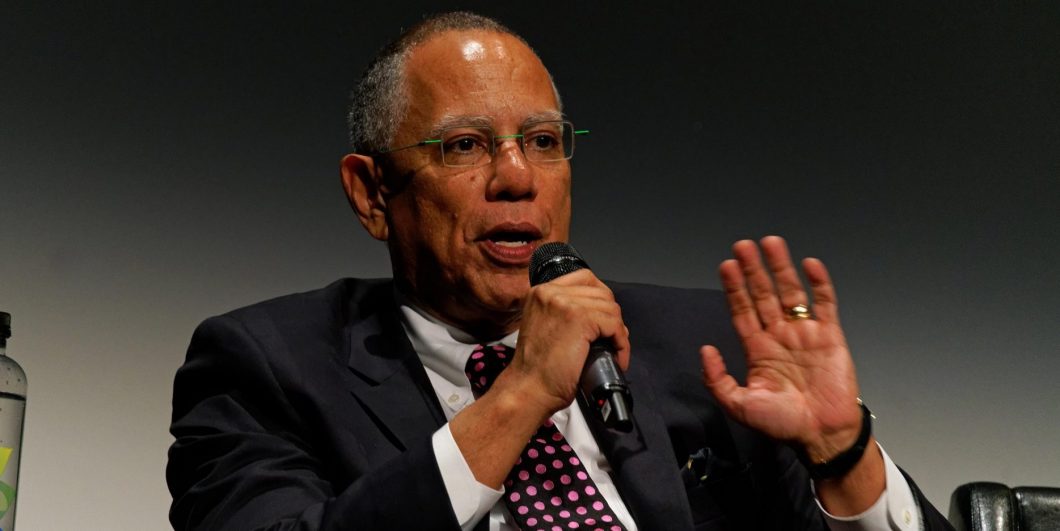

- Trump Derangement Syndrome: Furious with Trump’s election, the Times’s reporters and editors responded by making their paper the voice of the opposition. There is some evidence for this hypothesis. At a recent town hall for staff, the executive editor Dean Baquet suggested that when Bob Mueller failed to deliver the goods to get rid of Trump, reporters felt they needed to move on to another focus, like accusations that the administration was racist. However, the decline in editorial sensibility started before Trump and has appeared in sections, like Sunday Business, that bear little direct relationship to Trump.

- The Decline of Advertising Revenue: The Times now depends more on income from subscribers than it generates from advertisers. As a result, it panders to its subscribers’ views, which are predominantly on the left. And as it becomes more left-wing in its reporting, it attracts more left-wing readers and loses conservative ones, setting off a vicious spiral. It also has lost pressure from advertisers to keep to objectivity. The organization need no longer maintain a kind of reputation that comports with the makers of quality products that tended to advertise in the Times.

- The Postmodern Generation: The new generation of reporters have been educated in the postmodern university. They have a greater commitment to leftist causes than to the truth. The newsroom town hall provides some evidence for this: older editors tried to defend the need for objectivity against younger reporters, who were having none of it.

While Trump will not be President forever, the latter two factors are likely to continue to push the Times to become an ever-less-objective paper. Advertising is likely to continue to dry up. And students appear ever more woke. Indeed, at Harvard many students recently denounced the Crimson, its student newspaper, even for seeking comment from Immigration and Custom Enforcement on a story that disputed its practices. A future generation of reporters may even drop the pretense of objectivity.

As a result, today the Wall Street Journal has the better claim to be the paper of record. Its readers seek more objective news, because they are business people who lose money if they make mistakes about the world. And ownership of the paper by Rupert Murdoch probably deters many left-wing journalists from working there. In any event, I have recently broken the habits of a lifetime and only skim the New York Times to see where the left is going. The news pages of the Wall Street Journal are what make my breakfast table a window on the wider world.