Law & Liberty contributors offer their reflections on the man and his achievements.

The Last Gentleman of the English-Speaking World

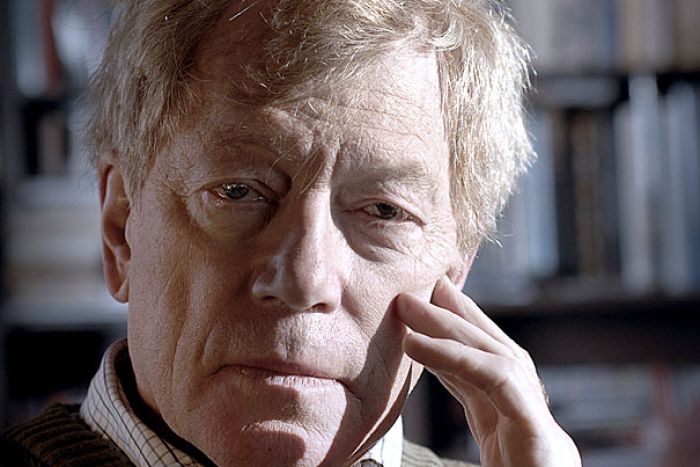

At 75 years of age, Sir Roger Scruton has died of the cancer that almost killed him last summer. A doctor admirer saved his life then, as he wrote in “My 2019,” an intervention that granted him six months to put his affairs in order. To borrow Churchill’s phrase, we may call Scruton the last gentleman of the English-speaking world.

First and foremost, his legacy depends on his very many writings. Trained as an academic philosopher and lawyer, Scruton wrote on many intellectual matters. He wrote even more on English conservatism and man’s quarrel with modernity, on the preservation of the environment, and on the Church of England, in which he did not believe, but which he considered an irreplaceable repository of English tradition in architecture and the other gifts of the muses.

He also entered boldly in the domain of the muses—he wrote on music, especially Wagner’s, and on architecture, in defense of the European heritage facing the oblivion of post-modernism. His other writings include two operas, several novels, and an essay on drinking wine. He published a staggering 60 volumes in all over the last 45 years.

It’s hard to find a comparable example of an intellectual so eager to prove the worth of high culture. Besides all his books, he lectured extensively, and many of his speeches can be found on YouTube, and he also wrote and presented a famous BBC program, “Why Beauty Matters.” He wished to prove that the consolations of beauty compensate the sufferings of this life, which politics cannot solve.

Scruton became such a spirited champion of nobility in reaction to his experience in Paris in May 1968, when he witnessed the shocking combination of an erotic revolution and a political protest. The children began screaming commands and he witnessed the threat of theoretical egalitarianism preached by an aspiring elite eager for tyranny. He became a firm, unyielding, and lifelong opponent of the political left.

This shows good judgment, but not good conduct—Scruton proved his gallantry, his penchant to take personal risks in a manly way, in the 1980s, when he repeatedly traveled behind the Iron Curtain to help set up educational opportunities for the dissidents who had been thrown out of society by Communist tyrannies, especially in the Czech Republic. He faced arrest, expulsion, and death, and earned honors from the Czech Republic, Poland, and Hungary.

His defining faith, a dedication to nobility, was much better rewarded in Eastern Europe than in his home, Britain, or elsewhere. Britain eventually knighted him, but not even this spared him from political humiliations in which his own Tory party participated last year.

His political judgment and political conduct thus proved superior to anything that might be said of intellectuals of the left in Britain and elsewhere. In an increasingly vulgar world, he was the last gentleman: contemptuous of contemptible people, a champion of freedom against tyranny, and of all the arduous achievements of civilization against barbarism, including the technological barbarism of the 20th century.

To fully understand him, it is therefore necessary to understand the vastness of his ambition. I summon before myself the image of Goethe, the only European who ever lived, who wrote nobly and thought ably about all things of importance to us as human beings. Only in such a portrait can we put together all the different achievements of Scruton, a man of Enlightenment and a Romantic, a daring writer and a conservative.

Scruton chose the life of a country gentleman. In 1993, he bought Sunday Hill Farm, where he lived the remainder of his life, finally able to be the kind of conservative he wished to be—one who conserves the land, who lives in fellowship with neighbors, and offers generously his gifts. A few years later, he met a young architectural historian named Sophie Jeffrys on a hunt, and in 1996, they married and made a home at Sunday Hill.

This happiness contrasts poetically with his upbringing in an unhappy, unprosperous home with a wicked father. Education proved to be his path to fame and fortune, and he took this to mean that he should always also offer the same gifts of education to his countrymen and, indeed, anyone who would listen. Aging in prosperity and happiness, becoming a father to Sam and Lucy completed him as a man, and must complete our story.

He was an admirable man and offered the spectacle of a love of beauty that doesn’t turn into crime or immorality or vulgarity, the applauded temptations of our times. Readers who would like to know more about him should begin with his Gentle Regrets: Thoughts from a Life, his novel Notes from Underground, and his most recent books on conservatism: Conservatism: An Invitation to the Great Tradition and How to Be a Conservative.

Since British left-wing elites hated him, we see necessity rather than chance dominating his educational activity, an unparalleled in his time attempt to define conservatism as the rejection of vulgarity. He applied the speeches of the intellectual and the heart of the aristocrat to the task of breathing life into our once exalted heritage. Where many conservatives speak sentimentally of Western Civilization, he sought to know and justify it by the highest standards of philosophers.