Maximum John Versus Tricky Dick

The scandal known as Watergate has proven unusually resistant to historical reinterpretation. Revisionist narratives of the Vietnam War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the entire Eisenhower presidency for that matter have appeared, leaving us with clashing accounts or sometimes a new synthesis. In contrast, a simplistic narrative of what was in fact a very complex scandal remains remarkably intact in the public mind. The critic Wilfrid Sheed noted this as early as the late 1970s, when he observed, tongue in cheek, that “Folks may be getting fuzzy about the Watergate details, but at least they remember the movie: a couple of nosy journalists and an informer, wasn’t it?”

Some of the reasons for this seem obvious. For 18 months, the scandal dominated the news cycle as few stories ever have, at a time (1973-1974) when news was the preserve of a few “powers that be,” to borrow David Halberstam’s phrase. These communications empires (corporate but often still family-run) dominated the media landscape and set the agenda. If blanket news coverage were not enough, the scandal also played itself out in two rounds of live televised hearings—first the Senate Watergate Committee’s investigation, followed by the House Judiciary Committee’s impeachment hearings—that were more entertaining and often more dramatic than the daytime soap operas they competed with. Having lived through a story that inched forward drip-by-drip, like Chinese water torture, Americans perhaps understandably developed a fixed idea of what happened.

But surely the overarching reason for the frozen narrative is the bestselling book All the President’s Men by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, and the eponymous movie starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman as the intrepid Washington Post reporters. The book, which appeared in mid-1974, months before President Nixon’s forced resignation from office, nominated several heroes—mostly from the Post newsroom—to offset what was a sordid and protracted saga of cover-ups, hush money, and break-ins in the wee hours of the night. The taut movie version, released two years later, applied the fixative. In a recent poll undertaken by Washingtonian magazine, All the President’s Men was named the best-ever film about Washington. That may or may not be true, but undoubtedly it has been one of the most influential.

Much less understood is that neither Bernstein, Woodward, nor Redford, one of Hollywood’s heavyweights, has been content to rest on their plaudits. Former Post publisher Donald Graham famously called journalism “the first draft of history,” but “Woodstein,” aided and abetted by Redford, have long been bent on seeing that their account is also the second, third, and fourth draft. Yale historian Beverly Gage noted as much in her 2013 review of a Redford-produced documentary timed to coincide with the 40th anniversary of the Watergate break-in. All the President’s Men Revisited “seems more like All the President’s Men Repeated,” observed Gage in Slate. She continued:

Redford sticks to the script first introduced . . . in 1974 . . . laying out how the ‘good guys’ in the media got the bad guy in the White House. We now know, however, that Watergate was more complicated than that.

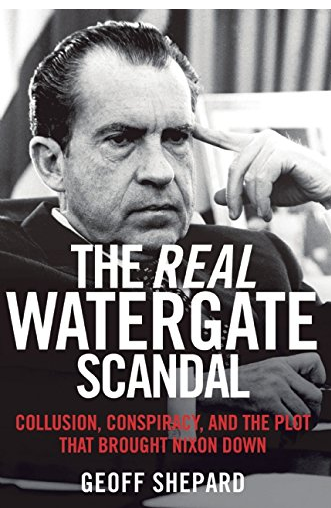

This is where Geoff Shepard’s new book comes in. The Real Watergate Scandal attempts to revise the narrative, though it is not Shepard’s maiden effort in this uphill battle. In 2008 he published The Secret Plot to Make Ted Kennedy President, which argued that the late Massachusetts Senator led an effort to turn a “third-rate burglary” into a mega-scandal that would not only diminish the political effect of Nixon’s landslide electoral win of 1972 but cripple the GOP, with the ultimate goal being the restoration of Camelot in 1976.

Shepard (an acquaintance of mine, I note for full disclosure purposes) is not a disinterested chronicler of Watergate. He was politically smitten by Nixon at an impressionable age, and in 1965, while attending Whittier College, the future President’s alma mater, he received a $250 Nixon scholarship (which the future President himself doubled). After graduating from Harvard Law School, Shepard worked in the Nixon administration for almost six years, first as a White House fellow, then as a senior staffer on the domestic policy staff, and finally, as the youngest lawyer on the President’s defense team. This new volume is actually an elaboration of arguments presented in Shepard’s 2008 book, which carried the subtitle Inside the Real Watergate Conspiracy.

The author’s accusations encompass the following: that Federal District Judge John Sirica conducted the trials of the original six Watergate defendants and subsequent cover-up conspirators in a highly biased and injudicious manner; that the co-conspirators should have been granted a change of venue outside the media hothouse of Washington, D.C.; that Sirica conducted ex parte meetings about Watergate with journalists, the chief counsel of the Senate Watergate committee, and the special prosecutors; and that some of the evidence of wrongdoing was either trumped up or woefully misunderstood in the media frenzy.

As the above suggests, much of Shepard’s outrage is directed at Sirica, a “false hero” who was nevertheless lionized by the media for his role in Watergate. The author says “Maximum John,” as Sirica was known owing to his harsh sentences, was an obscure and undistinguished judge before this case came along, his rulings frequently reversed on appeal. Citing an obscure but well-documented biography of the famed criminal lawyer Edward Bennett Williams, written by Robert Pack, Shepard reminds us of the close friendship between Sirica and Williams; the Williamses were godparents to Sirica’s daughter. More to the point, Williams’ law firm was counsel to the Democratic National Committee and represented the DNC in its civil lawsuit stemming from the June 17, 1972 break-in at its office in the Watergate complex.

Shepard argues that Sirica’s anti-Nixon zeal, and denial of due process to the President’s men who appeared in his courtroom, stemmed from this relationship. To anyone familiar with Edward Bennett Williams’ role in Watergate and his general behavior as a prominent lawyer, the suggestion is not outlandish. There was a reason Williams was considered the best criminal attorney in town by a wide margin: his politico-legal antennae were unsurpassed.

At a time when many people scratched their heads over who was ultimately responsible for the bungled burglary at DNC headquarters, Williams was confident that it led, at the very least, to the doorstep of the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), headed by former Attorney General John Mitchell. And despite longstanding claims that Williams (whose firm also represented the Washington Post) played no role whatsoever in the Post’s intensive coverage—other than bucking up executive editor Ben Bradlee when he expressed concern about going out on a journalistic limb—we now know that Williams was instrumental in leaking (to the Post and to other outlets) one of the most important stories to appear in the fall of 1972, as the accused burglars were awaiting trial.

This story was Alfred C. Baldwin’s account of the break-in. Baldwin, a former FBI agent, was the only participant in the break-in who was then cooperating with federal prosecutors. On the night of June 17 he had acted as the look-out.

If Williams, as Shepard insinuates, was whispering in Sirica’s ear, that would help explain the judge’s indefensible behavior when the burglars came to trial in January 1973. Sirica’s bias against the defendants disturbed even the three original federal prosecutors. He badgered witnesses whom he suspected of withholding information, most famously CRP treasurer Hugh Sloan, who actually was telling the whole truth insofar as he knew it. The judge also offered his own opinions of witnesses’ veracity in front of the jury and, as Shepard lays out, denied the cover-up co-conspirators a change of venue because he wanted to preside over their trial too. One doesn’t need to accept Shepard’s whole thesis to recognize that Sirica’s decision here was manifestly unfair to Messrs. Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell, et al. If these defendants weren’t entitled to a change of venue, then the concept of a fair trial before an untainted jury is devoid of meaning.

However, while it makes sense to trace Sirica’s injudicious behavior to his friendship with Williams, actual evidence is lacking. As Shepard is the first to admit, there is no record of what was actually said during the documented ex parte meetings, much less what may have occurred during undocumented ones. All that exists, really, is the suggestion of untoward, extrajudicial influence.

Another kind of problem crops up when Shepard describes what he considers unethical ex parte meetings between attorneys from the Watergate Special Prosecution Force and Sirica. The author draws inferences from a record that is admittedly scant and entirely circumstantial. He leaves out the context in which these meetings occurred, and the unprecedented substantive and procedural issues that were at stake. Could a sitting President be indicted by a federal grand jury for obstruction of justice? Or was impeachment the only proper recourse for presidential misconduct in office? Shepard also apparently made no effort to interview the lawyers who are still around who participated in these meetings. That makes his account read like a legal brief alleging improprieties rather than a fleshed out revisionist history, as much as one is needed.

Even if one were to accept parts or even most of Shepard’s argument—that Democrats’ single-minded pursuit of Watergate represented a partisan and ideological effort to overturn the 1972 election and “get Nixon,” regardless of the truth or consequences—his premise about what constituted the “real scandal” does not hold up. Regardless of Sirica’s bias and agenda, or the Senate Watergate Committee’s political cast, the June 17 break-in and the White House-orchestrated cover-up of that crime remain the genuine article. No one knew this better than Nixon, with his three decades of experience in national politics. He had no illusions about how Washington worked behind the scenes, and knew just what his political antagonists would try to achieve if he gave them cause.

Shepard’s effort at revisionism, ultimately, is ahistorical in that it ignores the best evidence we have: what was said on President Nixon’s taping system. It is largely forgotten now, but until the tapes’ existence was disclosed, the political and legal firewall represented by that famous pair of questions from Senator Howard Baker (R-Tenn.)—What did the President know, and when did he know it?—showed every evidence of holding firm.

There might be a legitimate dispute as to what constituted the real scandal if the tapes had proved that Nixon was as far removed from the cover-up as he was from the burglary. They did not. Rather, they established at the time, and more recently have underscored (through systematic efforts to improve the tape transcripts’ accuracy and completeness), that the President knowingly sanctioned the cover-up.

Revisionism based on new, previously misunderstood, or under-utilized documentation is a normal, even desirable, process. And showing that Nixon’s political antagonists did not play by the Marquess of Queensbury’s political code of conduct (if there is such a thing in Washington) ought to be incorporated as part of the overall Watergate narrative. But as a Founding Father of the Republic, John Adams, once noted, “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

Read Shepard’s response here.