The framers of the Constitution understood impeachment as a vital, potent legislative check on abuse or misuse of power or other serious misconduct.

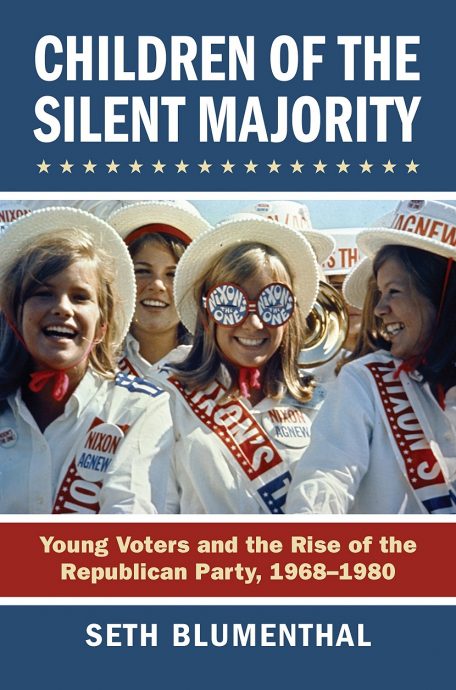

The Other Reason to Study “Nixon in ’72”: Its Youth Outreach

The period we think of as the Sixties actually ended at many points, all of them after 1970: the “peace” accord with North Vietnam in January 1973, the return of our prisoners of war shortly after, the longish recession sparked by the Arab oil embargo that autumn, President Nixon’s resignation in August 1974, the fall of Saigon to the North Vietnamese in April 1975.

But another moment of closure came with a choice by the voters: Nixon’s landslide reelection in what had, for some years, been a terribly divided nation. After his seemingly radical challenger was routed in 1972, it was easy for conservatives and moderates, battered by a decade of once-unimaginable changes, to hope that America might enter a new age of domestic tranquility like the 1950s.

The Baby Boom generation, a historically large one, would have something to say about that. In 1972, many of them were casting their first votes for President. There was also a great influx of college-age youth into the electorate that year after a constitutional amendment reduced the voting age to 18.

Author Seth Blumenthal, a senior lecturer in the College of Arts and Sciences at Boston University, shows the extent to which Nixon worried about this new political demographic, allowed it to influence his policy choices as President, dedicated a substantial part of his campaign to it, and ultimately succeeded in blunting the Democrats’ apparent advantage among these voters. “Nixon isn’t going to carry the college vote,” one presidential aide conceded, but “the margin by which he loses it is important.” In the end, Senator George McGovern (D-S.D.) won just 52 percent of the voters under age 25. Nixon won the support of many first-time voters who weren’t conservative—and they chose him over an opponent who was a hero to many other young people.

How to Politically Channel Ambivalence

How did it happen? This book explains in some depth, starting with a well-chosen title, Children of the Silent Majority, that points to a great social fact: Most Americans in that era were passive or distressed bystanders, either rejecting the “Sixties” mentality, reserving judgment, or simply confused. That distinction—between rejecting the Sixties and feeling unsure about it—was central to Nixon’s strategy.

It was his televised November 1969 address from the Oval Office that did much to popularize the term “silent majority.” In the speech, the President called upon Americans, with a telling ambiguity, to be both “united for peace” in Vietnam and “united against defeat.”

Nixon could expect full support from voters who were fundamentally against defeat, given the “Come Home America” platform on which the vehemently antiwar McGovern was running. But what of those who were fundamentally for peace: the moderately antiwar moderates who had felt relieved or sympathetic, not suspicious or triumphant, when President Johnson, in what ended as a kind of resignation address on March 31, 1968, said he wanted to speak to his fellow Americans about “peace in Vietnam”?

Blumenthal shows that Nixon and his campaign team had a sophisticated understanding of young people’s potential significance in Election 1972. They perceived the possibility that attracting younger voters might bring more support from Americans in their thirties or even forties, from the kids’ parents, and from moderates who wanted their President to have more popularity among the next generation.

The President’s campaign for reelection effectively played up the progress he was making toward an agreement with Hanoi and his decision to end the draft. It highlighted détente with the Soviet Union and, of course, Nixon’s historic opening to communist China. It talked up the importance of America’s youth. Indeed, according to Blumenthal, the President had become more liberal in domestic policy by 1972 partly because he wanted or thought he needed the votes of younger people:

after the voting age fell to eighteen, Nixon acquiesced on youth issues. On the environment, young people from across the political spectrum shared ecological concerns. Nixon’s administration could not resist demands for new regulations when an equally diverse cross-section of congressional members advanced laws that protected air and water from pollution. … [and] Nixon’s move to end the draft served as the piece de resistance in his administration’s effort to control the generation gap’s political damage. … Hardly the ‘evil genius’ in this realm, the president acted defensively. Many historians magnify Nixon’s Machiavellian leadership and overlook the pall of confusion that youth politics cast over his administration.

There is some polling evidence to suggest that even the wage-price controls he imposed on the economy in 1971, denounced by orthodox conservatives, may have helped Nixon with young voters.

In personal terms, the strategy for appealing to the youth demographic emphasized Nixon’s experience, knowledge, intelligence, and sobriety. Research for the campaign early in the 1972 cycle indicated that young people did not find him “relaxed,” “warm,” or “extroverted,” to be “up-to-date,” or to have much of a sense of humor. But as Ken Rietz, the Nixon youth organization’s director, remarked: “Most young voters do not want a president who is one of them . . . just as the majority of young people do not want a father who is a pal.” A September 1972 poll indicated that a striking 57 percent of young voters found Nixon “more sincere” than McGovern (who had, however, made various missteps by then, including his handling of Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton’s short-lived nomination for the vice presidency).

This raises a question that might have been worth considering in Children of the Silent Majority. The book gives little impression that Nixon had any particular rapport with or empathy for the young generation, or much interest, except a strictly political one, in its perspectives. But do we really know that? Nixon had a little-remembered sentimental side: witness the eloquent note in his 1968 acceptance speech about the underprivileged young man whose heart is broken by an American “system” that might, in addition, “take his life on some distant battlefield.” Or his impulsive pre-dawn chat with young demonstrators at the Lincoln Memorial several months after his “Silent Majority” address.

Although the Nixon campaign reached out solicitously to young men and women who weren’t attending college—a vast and somewhat more conservative group that was mostly ignored by the media and the organized Left—its messaging lacked much ideological content, with little explicit opposition to Sixties leftism.

A Time of Street Brawls and Left-wing Terrorism

One reason for this was probably a reaction to the Republicans’ failure to gain ground on the Democrats in the 1970 midterm election despite its being held amid a virulent phase of “activism”—not just street brawls but terrorist acts—on the part of the extreme Left. The median voter, it seemed, had failed to see all of this as in any way a partisan issue. So why talk about it in 1972? A politician as pragmatic as Nixon wouldn’t be inclined to. (The silent majority, his moderate Democratic White House aide Daniel Patrick Moynihan warned in a 1970 memo, “is silent because it has nothing to say.”)

In addition, Blumenthal points to an apparently strong belief among the President’s campaign strategists that moderate and even some conservative young people would dislike any attack on others of their age. Nixon therefore stuck to praising the youth who were, in the language of the day, relatively “square” and wanted, as the Nixon messaging stressed, forward-looking but realistic solutions to domestic and international problems.

The Nixon youth effort, Young Voters for the President, can thus be said to have been a positive campaign. It also functioned as a basically self-contained, although certainly not independent, campaign apparatus run by the young. This meant it offered a good “opportunity for leadership for people under thirty or even twenty,” YVP leader Hank Haldeman, the son of White House chief of staff Bob Haldeman, later recalled. Participants often thought of it as a chance to hold major responsibilities and start building toward a career.

Also significant was the relative absence, according to Blumenthal, of active right-wingers in the YVP. The conservative movement’s youth group founded in 1960, Young Americans for Freedom, tended to dislike Nixon as an establishmentarian moderate, and its members who backed the President weren’t especially welcome in the campaign. Indeed, “we didn’t even get along that well with the Young Republicans,” one YVPer told the author. “They were all about the platform and we were all about the candidate.” And the candidate ran clearly toward the center, if in any direction at all.

The organization that would later become so famous or infamous, the Committee to Re-Elect the President, printed decorative stamps for the backs of envelopes with Nixon’s image and the motto “Generation Of Peace,” their first letters highlighted to say “GOP.” As a sign depicted in one of the campaign’s television ads put it: “Happiness is Nixon.”

Far-Reaching Effects Beyond 1972?

There is little in Blumenthal’s account of the President’s 1972 youth effort, then, that would gratify a conservative reader—unless one agrees with his conclusion that it bore additional fruit for the Republican Party in 1980, 1984, and beyond. This claim about the future has two aspects.

First, Children of the Silent Majority shows that many of the youngsters who worked for Nixon’s reelection remained involved in the GOP for years, even decades, afterward, often rising to higher positions in its service. (Did they have a net ideological, or any other definite, impact on the party? It isn’t clear.)

Blumenthal also suggests that the campaigning for Nixon by many blue-collar and Southern youth in 1972, including a project called Operation Kinfolk, likely helped to make their Democratic parents friendlier toward the Republican Party. Although these topics, unlike the YVP as a whole, aren’t discussed in great depth, they are welcome attempts to broaden what would otherwise have been a duller tale about a publicly cautious reelection drive by a calculating President and his technocratic political managers.

Many readers, nonetheless, may find that the book is too much about the Nixon campaign, and too little about the children of the silent majority as full people rather than voters—what they really thought of the Sixties, the upheavals it brought, all the new styles and behaviors that took hold, the harsh tactics and rhetoric their loud peers on the Left used in confronting society. To what extent were these young “forgotten Americans, the non-shouters, the non-demonstrators”— Nixon’s description of the silent majority in his acceptance speech at the 1968 Republican convention—really like the older generation’s Nixon voters? How similar were they to Mom and Dad in their essential attitudes? How different?

They were, Blumenthal notes occasionally, more liberal while also more independent of parties. He also cites a survey that found non-college youth had “virtually caught up with college students in adopting the new social and moral norms.” But it would be good to know more.