The Pastoral Mencken

Et in arcadia even Henry Louis Mencken, the city boy and scourge of those so lacking in urbanity, the booboisie.

Mencken’s boyhood summers in rural Maryland were spent exploring dew-covered meadows and ancient woods, cool brooks and busy barnyards. Back in Baltimore for most of the year, he and his brother, with the rest of their “gang,” defended the edges of their own territories between forays into others’, lifting the occasional sweet potato from a grocer for illicit feasts. Arcadia being what it is, though, the barefoot reveler runs afoul of a stray nail in the manure and the yam-snitcher afoul of paternal suspicions.

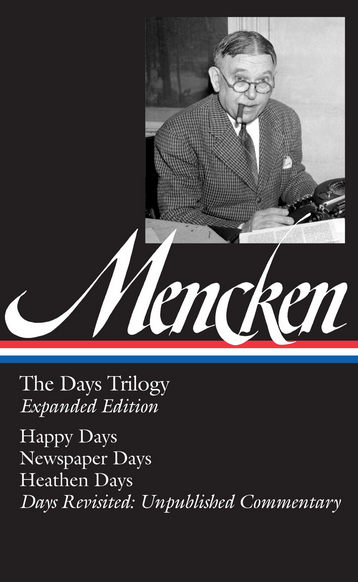

The Library of America’s handsome new single-volume edition of his three memoirs—Happy Days, Newspaper Days, and (naturally) Heathen Days—offers them considerably enriched by the addition of his own notes and emendations. Days Revisited provides nearly 200 pages of previously unpublished commentary, compiled in the form of footnotes or annotations by Mencken in the late 1940s and embargoed for some years after his death. Gracefully edited by Mencken biographer Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, the new volume makes comparisons simple, with careful page and line citations and a few scholarly notes on the text.

Baltimoreans may remember more than others that the Sage of Charm City was also its psalmist—Mencken dropped the mordancy when he titled his boyhood memoir Happy Days. Because of his great fame in the era of Prohibition and the Scopes trial, and his reputation as the early editor of so many of the modernists, it’s easily forgotten that Mencken was born in 1880. When, as he puts it, he was introduced to the universe, only 15 years had passed since the end of the Civil War. Baltimore was lit with gas, traversed by horse-power, and pretty medieval in its sanitary arrangements.

Mencken seems to remember it all, exuberantly. Born securely into the German American community of West Baltimore, he describes its hierarchy and mores in detail (along with the “Middle Bismarck” style of interior decoration).

His early schooling takes place in F. Knapp’s Institute, run by the eponymous Professor, who, though “much more diligent at praise than blame,” was also “a virtuoso with the rattan.” Corporal punishment so meted out was choreographed to the count of “eins . . . zwei . . . drei . . . ” It was considered proper etiquette for the chastisee to make an appropriate howling noise and massage his rump on the way back to his seat, upon which Professor Knapp always reminded him, “You can’t rub it out.” It’s not an uncomplicated picture—for on the other hand this was an educator who took in students of numerous nationalities, and was widely recognized as a teacher of the deaf, whom he had been teaching to read lips since the mid-1800s.

Outside of school Mencken, with brothers, cousins and friends, led a life of freedoms that seems almost as ancient to us as recitations and rattan. The boys who clumped together into their neighborhood clubs or gangs fought some, but mostly did things like gallop headlong for some blocks, then turn and gallop back. They gathered various treasures from the street, bottle caps or cast horseshoes, and played elaborate games with tops and marbles. They hung out at livery stables and hitched dangerous rides on the backs of streetcars. (Of course some of the joys he describes aren’t lost: He recalls playing in the snow, “inscrib[ing] it with wavering scrolls and devices by the method followed by infant males since the Würm Glaciation.”)

And naturally Mencken explores the fine points of nickname onomastics, pointing out that his friend Barrel Fairbanks achieved the middle way by being too fat simply to be called “Fats” and not fat enough for “the satirical designation of Skinny.” The taxonomy of “cops and their ways” notices the heavy moustache that “went in those days with the allied sciences of copping and bartending.” And the boys actually warned one another with “Cheese it!”

But among all the descriptions of home life, sarsaparilla drunk in saloons where a father was conducting business, and even recipes for cough syrup, a particular epiphany catches our attention. Describing himself in “the larval stage of a bookworm,” Mencken arrives at “probably the most stupendous event of [his] whole life.” From among a household trove of good books, bad ones, and the positively awful ones of the era, young Harry plucks The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The encounter with its “domain of new and gorgeous wonders,” described years later with such delight, suggests the growth and deepening of his appreciation for language and what it can do.

By the era of Newspaper Days, Mencken’s love of reading has been joined by a love of writing and the determination to become a newspaperman. Earlier in the 1890s, when he finished secondary school at the Baltimore Polytechnic (first in his class), he’d done as expected and followed his father into the family cigar business. It’s only with the harrowing death of his father in early 1899, described in detail in Days Revisited, that the young man realizes he’s free of the filial business obligation and sets out to land a newspaper position.

He starts at the bottom at the Baltimore Morning Herald—in fact he hangs about the city-room until he’s finally sent to cover the police beat in low areas and high, magistrate’s courts, and the introduction of a “cineograph” showing moving pictures. Soon he’s wearing out shoe leather covering fires, mayhem, Cardinal Gibbons, and the occasional hanging.

The great adventure of his early newspaper days is doubtless the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904. “We had a story, I am here to tell you!” says HLM. He left his home midmorning one Sunday and returned in a week, in the meantime bearing witness, with his colleagues, to the fire that blazed on and on, “cremating” at least 20 fire engines, burning out all but one Baltimore newspaper and three hotels and “every office building without exception.”

On that first Sunday evening, just as the Herald was about to go to press, all the staff from pressmen to editors were rousted by the firemen and, carrying proofs and the logotype, left the building for what proved to be the final time. The story of their quest for substitute printing machinery—which took them from Washington, where they published an edition at the Post, back to the beleaguered Baltimore World, and then to Philadelphia, where they were able to use the Evening Telegraph presses—still makes the heart race. A major revelation was the hideous discovery, when fire companies from neighboring counties and states arrived, that hosepipes and hydrant couplings weren’t standardized. The outcome was obvious, and horrifying. Astonishingly, the papers reported no deaths in the fire and a bare handful afterwards, from exposure. (A glance at file photos of this disaster, showing a city reduced to a moonscape, will illuminate how unlikely this was.)

Mencken says that he went into the Great Fire a boy and emerged “almost a middle-aged man” (he was 23). Certainly his considerable energies hadn’t flagged—he was the Herald’s drama and music critic, once writing 23 unfavorable notices in a row. He parried numerous requests to serve more as a publicist than a reporter, and remained on drinking terms with the requesters. Into the bargain he is full of anecdotes of Baltimore as it then was, remaining ever a connoisseur of the livelier aspects of minor crime, amateur amorists, gastronomic over-achievers and professional drinkers. That last term is meant literally. In Mencken’s early years, there were quite a few of these, who represented their respective breweries at saloon openings, church feasts, and the weddings and funerals of saloon keepers, at the last of which they were also professional mourners.

It’s at about this point that Heathen Days overlaps. Aside from some coverage of the 1920 political conventions and the Scopes trial of 1925, the heathenness is mostly of the usual sort. This third volume compiles memories that didn’t make it into the previous two, from the early story of the uncouth Hoggie Unglebower, to high school recollections, to reminiscences of sea voyages, a Cuban revolution, and, mirabile dictu, an audience he and a companion had with the Pope. During this last, Mencken noticed “that the huge Masonic chain hanging from [his friend’s] watch-chain was plainly in view. I whispered a warning to him, and he thrust it into the fly of his trousers.”

There are many more charming moments. The glimpses of Baltimore’s Bonaparte or of Basil Moxley, who took the tickets at Ford’s the night Mr. Lincoln came to see the play; the “glutton who lived at the Rennert Hotel”; the German madame made happy by Mencken’s sending her a postcard from her hometown of Würzberg; even Mr. Berger’s still locally available black and white cookies—are only threads in the richly woven fabric of Mencken’s Baltimore recalled. He is a sort of a daemon of his time and place, a local demigod likely to be propitiated with a good schooner of beer.

In a note reflecting on the reception of the first Days volume, Mencken expresses surprise at having heard from so many women. He says that when he was a boy it didn’t occur to him that girls might be having anything like the same experiences as he had, in

a time when people could spend days, weeks, months and even years without being badgered, bilked or alarmed . . . I enjoyed myself immensely, and all I try to do here is to convey some of my joy to the nobility and gentry of this once great and happy Republic, now only a dismal burlesque of its former self.

What are we to make of this benignant HLM, so demonstrably removed from the Juvenalian knife-thrower of so much of his journalism and other essays?[1] I think the memoirs illuminate his other work. They don’t rescind his judgment, and certainly there are abundant glimpses of the Great Generalizer throughout. Mencken possessed, to an exaggerated degree, that common human disposition which characterizes and dismisses great swathes of people in classes yet responds to the individual case with delicacy and good sense. Mencken certainly demonstrates this quality in his actions; he seems, for example, to have been a considerate and respectful employer to various household staff at the same time that he tossed off callous bons mots about “Aframericans” without seeming to make any connection.

Mencken had the vices of his virtues, and vice versa. He seems to have been born certain of his rightness of judgment and his election to the bench. But he offered his opinions; rarely does he seem to have wanted them simply imposed on others. In this way he exercises and champions a liberty that is actually antecedent to dogma or party—a nearly pure freedom of thought and expression. Untrammeled as he was by Matthew 22, he laid about him with a right good will, identifying charlatans, mountebanks, dupes, morons, idiots, and all the fools we’re nowadays prohibited from calling by name.

In the Days essays, Mencken shows that the gimlet eye does not have to be a jaundiced one. When snark is the feeble substitute for irony, emotion for thought, spin for accuracy—indeed, when political correctness bids fair to smudge the edges of any clear picture—the joyous Mencken offers along with the saturnine one a clarifying example and a guide.

[1] I am indebted to Henning Jensen for reminding me about Juvenal.