A reflection on the promise and limits of American power in Afghanistan.

The Problem of “Frenemies”

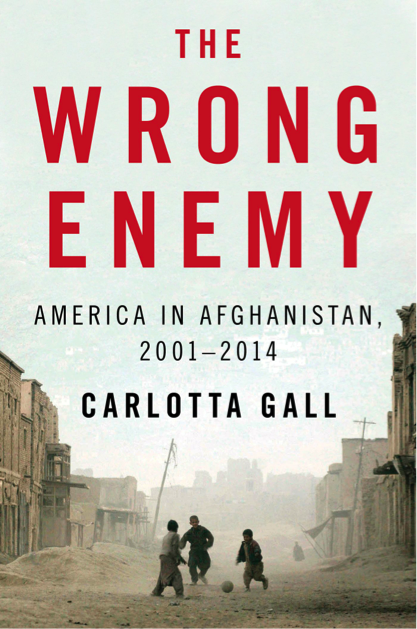

Carlotta Gall, a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist for the New York Times with 10 years of experience covering the American war in Afghanistan, argues that the United States has been fighting the wrong enemy in Afghanistan. The enemy is not the Taliban, but rather Pakistan, which manipulates the Taliban and other Islamist groups to wage proxy wars against it neighbors in Afghanistan and India.

As a journalist, Gall makes her case through judiciously chosen and narrated vignettes. She is careful not to reveal her sources, but one story after another enables her to build an overwhelming circumstantial case that Pakistan is what American service men and women call a “frenemy” or an “enefriend.” At times it cooperates with the United States, which needs to send supplies through Pakistan to support its forces in land-locked Afghanistan and needs the aid of Pakistan’s Inter-Service Intelligence agency, a.k.a. the ISI, to track terrorists in Pakistan. And Pakistan has been compensated generously for this cooperation: since 2001, it has received over $20 billion in U.S. aid, mainly to modernize the Pakistani military.

At other times, however, Pakistan undermines American efforts in Pakistan, most notably by supporting the Taliban against the Afghan government in Kabul. Pakistan supplies the Taliban a sanctuary in which to train, supply, rest, refit, regroup, and attack Afghanistan again and again.

Gall is a courageous woman. As she explored the links between Pakistan and the Taliban, she was monitored closely by Pakistani intelligence, and in one case, even beaten up by its goons. For many Americans who have served in Afghanistan, her claim that Pakistan has been manipulating the Taliban is not new. Indeed, it is as commonplace a story as dog bites man. In Gall’s defense, however, one might note that sometimes one must talk about the gorilla in the living room. The mainly circumstantial evidence she supplies of Pakistani complicity not merely with the Taliban, but even with Al Qaeda, is a kind of civic education for Americans who find this conflict difficult to fathom. And if she is right that Pakistan’s ISI actually had an intelligence office designed to shelter Osama bin Laden from American reprisals, it is certainly time to wake up and recognize that right now Pakistan is more of an enemy than a friend of the United States.

To avoid moralizing, however, one needs to think about the Pakistani side of this story. Pakistan sees the United States as an unreliable partner. In 1979, to obtain Pakistani help for “freedom fighters” against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Carter administration turned a blind eye to Pakistan’s nuclear weapons development program. The Central Intelligence Agency, fighting “Charlie Wilson’s War,” was none too scrupulous about the Islamist extremists it abetted Pakistani intelligence in recruiting to fight the Soviets. And when the Soviets pulled out of Afghanistan in 1989, the Bush administration hypocritically slapped non-proliferation sanctions on Pakistan and cancelled the sale of F-16 fighter planes to the Pakistani air force.

Pakistan was left holding the bag for millions of refugees from Afghanistan as competing warlords sought to establish their control. With India supporting an alliance of northern tribes, Pakistan responded by supporting the Taliban, the name given the religious students who responded to the call for jihad and eventually came to control most of Afghanistan before the American invasion in 2001. Since the United States has abandoned Pakistan before, it is only natural that Pakistanis think about their future after the Americans leave Afghanistan.

Because the United States has spent more than a trillion dollars and its military has suffered over 2,000 combat deaths in Afghanistan from 2001 through 2014, Gall is well aware that the American public’s support for continuing efforts to save the government in Kabul from the Pakistan-sponsored Taliban insurgency has dwindled to somewhere between feeble and non-existent. Nonetheless, she believes failure to continue the struggle would have far-reaching consequences. Without continuing support to the Afghan government from the United States and NATO, not only is the Taliban likely to return to power in Afghanistan, but also Islamist groups around the world would receive an enormous boost to their morale if they could claim that they had defeated not one, but two superpowers, first the Soviet Union and then the United States.

If the final result of America’s longest war is that the Taliban regains control of Afghanistan and supplies a sanctuary to Al Qaeda and associated movements to attack the United States and its allies again and again, the United States might be compelled to intervene again too, so why not finish the job it set out to accomplish in 2001?

That seemingly rhetorical question is not easy to answer. It requires carefully examining the options that were once, and are perhaps still are, available to us. It also requires calibrating American objectives to the available means for accomplishing them and the will of the American people to use them. Above all, it requires careful attention to the strategic environment in and around Afghanistan, which may well be the worst possible place for the United States and its proxy, the Afghan government, to wage a protracted counterinsurgency.

Gall believes the course of the war has been marked by numerous lost opportunities since 2001. The moment of maximum leverage for the United States was after the fall of Kabul in 2001, when the Taliban government was overthrown and Afghans truly did dance in the streets (because the just-vanquished Taliban had forbidden them to listen to music). However, not only did the United States fail to pursue Al Qaeda vigorously enough to destroy its cadres, and perhaps even capture Osama bin Laden, in the Battle of Tora Bora in December, 2001, for example; it also failed to use its leverage to reconcile moderate Taliban, however defined, to the new government in Kabul. By excluding all Taliban, who usually have little more than a religious education in the madrassas and often have known nothing but war as a vocation, the United States put them on what Sun Tzu called “death ground.” They had little choice but to find work as insurgents. They had solid resumes based on decades of fighting first the Soviets, then the mujahidin factions in Afghanistan, and then the Northern Alliance. All they needed was support – and a sanctuary in which to regroup.

Pakistani officials have many reasons to employ the Taliban. Afghanistan is a safety valve against Islamist violence in their country. Better to send the graduates of the madrassas to Afghanistan than deal with them at home. Better to tie the United States and NATO down in a quagmire they desperately wish to escape than deal with a pro-Western government in Afghanistan. Most pressing of all, from the Pakistani point of view, is the need to acquire strategic depth against India, against which Pakistan has waged five wars against since partition in 1949. (It lost all of them, with one leading in 1971 to the secession of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) from West Pakistan (now just plain Pakistan).

Take a look at a map. Pakistan holds just a sliver of territory in the north between India and Afghanistan. In modern mechanized wars, Pakistan could lose such territory within days. Because Pakistan is unlikely to win a conventional war with India, it has adapted— first by becoming a nuclear power, and second, by sponsoring terrorist organizations, including the Taliban. The Pakistani military, which Gall sees as a kind of state within the state, needs space to retreat. It needs allies among the Pashtuns of Afghanistan, who are kin to Pakistan’s own Pashtuns in its northern territories.

Pakistan needed not merely a motive, but also an opportunity to wage war, by proxy, against the United States and Afghanistan. Quite rightly, Gall identifies the American war in Iraq as such an opportunity. By 2003, Americans were in a hurry. They had already changed the regime in Afghanistan, and had concluded, prematurely, that the struggle with the Taliban was over; Al Qaeda had scattered to the four winds. The Bush administration believed it was time to make an example out of states presumed to have active programs to develop weapons of mass destruction, especially states that had a history of cooperating with terrorists (though not necessarily with Al Qaeda). Iraq was the test case to send the message to such states to change their policies, quickly, or be overthrown.

This momentous strategic decision had enormous opportunity costs, however. U.S. forces that might have been used to stabilize Afghanistan enough to prevent a Taliban resurgence were instead sent to Iraq, or redeployed from Afghanistan to Iraq as its multi-faceted insurgency began to escalate out of control. As the years went by, American forces sent to Iraq came to substantially exceed those sent to Afghanistan. Afghanistan became the forgotten war as Iraq soaked up ever more American resources, attention, and will power. Knowing that the United States was 1) bogged down in Iraq and 2) in need of access via Pakistan to supply American forces in Afghanistan, the Pakistani military and the intelligence service could calculate that they would pay no significant price for supporting the Taliban insurgency.

Ironically, the war in Iraq proved ideal for rallying Islamists to fight the so-called crusaders, meaning the war increased rather than decreased the influence of Al Qaeda in Iraq, with a splinter group, ISIL (the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant) coming to control huge swaths of Iraq and Syria in 2014. With the American military overextended in Iraq, the American government neglected the theater from which it had been attacked, originally, on 9/11, and now, in 2014, some Taliban in the Pakistan province of Baluchistan have pledged allegiance to ISIL. Americans thought that Afghanistan was already secure, but the unintended consequence of destabilizing Iraq was to give a terrorist organization even more ruthless than Al Qaeda a foothold in Afghanistan. It is not easy to imagine a worse outcome for these interconnected wars.

As was the case in Iraq under the leadership of General David Petreus between 2006 and 2008, the United States did eventually reassess and begin to adapt to increasing Taliban attacks in Afghanistan with the “mini-surge” of U.S. troops in the first years of the Obama administration. Quite rightly, however, Gall observes that had the United States concentrated more on Afghanistan and adopted a counterinsurgency strategy, including reconciliation with moderates, early in 2003, then the Taliban might not have made such progress that, by 2010, it appeared to be on the verge of encircling Kabul and had much of southern Afghanistan under its control. Indeed, the direct costs of the war in Iraq now exceed two trillion dollars. Had only a fraction of these funds been used to persuade Pakistan to disown the Taliban and cooperate more completely in hunting Al Qaeda, American victory in Afghanistan, defined as preventing Afghanistan from becoming a sanctuary for Al Qaeda, might well be secure by now.

As a journalist writing the “second draft” of history by looking back at more than a decade of conflict in Afghanistan, Gall rarely addresses what might be the best match of policy and strategy for the United States in Afghanistan today, but we are free to do so ourselves. A strong case could be made that the American war in Afghanistan is currently unwinnable. So long as Pakistan wages a proxy war with the United States via the Taliban, and the United States is unwilling to get tough on Pakistan, the Taliban can survive and even prosper, as American and NATO forces dwindled to approximately 11,000 personnel (mainly for training the Afghan military) by the end of 2014.

Because Pakistan is a nuclear-armed state, with a population of almost 200 million people, many of them deeply hostile to the West, the United States is unlikely to take any military action against Pakistan. Indeed, because the United States depends on Pakistan for logistical and intelligence support, one might say the United States needs Pakistan more than Pakistan needs the United States. That is an important reason why American officials rarely talk about the Pakistani gorilla in the living room. Primarily to appease the United States, the Pakistani military has occasionally engaged the Taliban in Pakistan’s northern territories, but because Pakistan needs the Taliban for its own strategic purposes, its efforts so far are best described as feeble and half-hearted.

Progress seems unlikely until Pakistan comes to fear the Taliban more than it fears India. It has some good reasons to do so. After all, in December 2014, in response to somewhat more vigorous Pakistani military raids on its strongholds in northern Pakistan, the Taliban attacked a Pakistani school on the outskirts of a Pakistani military base in Peshawar, killing at least 141 people, 132 of them children. Many were the children of Pakistani officers. And this is not the only time when the sorcerer’s apprentice has turned against its master.

Do not hold your breath waiting for Pakistan to settle its outstanding quarrels with India and concentrate on destroying the Taliban, however. For readers of a journal devoted to law and liberty, perhaps the most important lesson to be learned is that in any country where the military and intelligence services function as a state within a state, there can be neither law nor liberty—nor rational foreign policy. Such was the fate of Serbia in July, 1914, when the Serbian intelligence service undermined the Serbian government’s more pacific policy toward Austria-Hungary by sponsoring a terrorist organization, the Black Hand, one of whose members assassinated the Austro-Hungarian Archduke Ferdinand, thus providing a catalyst for the First World War. In 2001, terrorists sponsored by Pakistani intelligence attacked the Indian parliament, an act that could have sparked another war between India and Pakistan. And in 2007, Gall argues, the Pakistani military and intelligence services turned a blind eye to reports that Al Qaeda would attempt to assassinate the new Pakistani prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, whom they killed that year, in part because she was more willing to make peace with India and crush the various Islamist groups in Pakistan.

To paraphrase Friedrich Nietzsche, of all the world’s stupidities, the greatest stupidity of all is to engage in a titanic struggle and forget what one is fighting for. In truth, America’s primary enemy in this conflict is neither the Taliban nor Pakistan because their objectives are primarily local and regional; quite accidentally, both were caught in the crossfire between the United States and Al Qaeda and associated Islamist movements whose global ambitions required them to attack the United States directly. The beginning of strategic wisdom in this conflict is to keep our eyes on the prize and not get distracted by accidental conflicts.

Neither the Taliban nor Pakistan must necessarily be enemies of the United States because neither of them has global ambitions. In theory at least, it might be possible to follow the advice of Sun Tzu to “attack the enemy’s alliances,” that is, to separate Al Qaeda and its ilk from the support of the Taliban and Pakistan alike. Unfortunately, the prospects for American success in Afghanistan, defined very narrowly as preventing Al Qaeda, our primary enemy, and associated movements from gaining a base in Afghanistan from which to attack the United States again, are not good in the short term. Perhaps the best one can hope for at present is that the residual training forces enable the Afghan military and police to hold on in their war against the Pakistani-Taliban coalition.

In the long run, progress depends very much on events and circumstances the United States cannot control, though it might influence them at the margins. Perhaps the highest priority needs to be ensuring that elected civilian governments in Islamabad are not overthrown by the Pakistani military and doing all that is possible to enable such governments to gain control of their military and intelligence services. Only when Pakistan becomes a genuine state, with elected governments, bound by laws and having a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, is it likely that Pakistan will understand its best interests, make peace with its neighbors, and crush the fanatics who attack schools, murder children, and support our primary enemies, the ones who wish to attack the United States and its citizens at home and around the world.