Just Before the Return of the Strong Gods: On Charles Péguy’s Temporal and Eternal

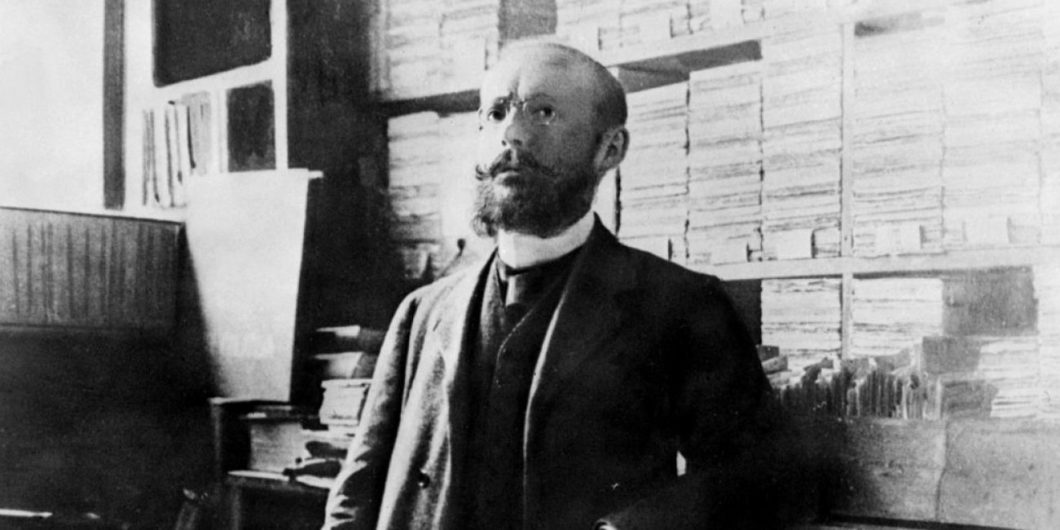

The French poet and essayist Charles Péguy’s “Memories of Youth” emerged as an apologia for his life amid a condition of embarrassment and even shame. From its defensive search for explanations and efforts to justify the author’s own early political engagements came into being a winsome, obscure, but finally compelling vision of political life as having a religious dimension and so also a claim—subordinate to Christianity but real nonetheless—on our binding fidelity, our pietas.

Like Dante before him, Péguy was a poet of the Church and the Nation, and one who, like Virgil, conceived of life as a series of overlapping, hierarchical loyalties to communities greater than ourselves. Péguy’s “Clio I” gives voice to that devotion and rebukes the modern age, modern Christians included, for its renunciation of piety to the eternal element threaded through the heart of the historical, created world. “Memories” and “Clio” together constitute this classic little book, one of the few of Péguy’s translated into English, Temporal and Eternal.

A Scapegoat for the Nation

In 1894, a Captain in the Army of the French Republic, of Jewish ancestry, Alfred Dreyfus, was convicted of espionage and sentenced to imprisonment on Devil’s Island. Before long, independent investigators would discover that his conviction was wrongful, and that Dreyfus had been framed by means of forged documents. The political right, largely Catholic and frequently anti-Semitic, persisted in seeing Dreyfus as a villain; the right was also the party of the military class, one still smarting from the humiliation of the Franco-Prussian War almost three decades earlier, and considered doubts about Dreyfus’s guilt to be an act of treason, as it would yet again cast shame upon the French Army. The anti-Dreyfusards were therefore the party of loyalty to God and country, and one more than willing to offer up the Captain as a scapegoat for the sins of the recent past. Péguy would write of them, that their “true position”:

Was not of saying or thinking Dreyfus guilty, but of thinking and saying that whether he was innocent or guilty, one did not disturb, overthrow, or compromise, that one did not risk, for one man’s sake, the life and salvation of a whole people . . . And the first duty of a people is not . . . to endanger itself for the sake of one man, whoever he may be, however legitimate his interests and his rights.

The Dreyfusards who rose to the Captain’s defense saw the exact same phenomenon but from an opposed perspective. Dreyfus was being forced “to devote himself to France” as a scapegoat, as another Christ offered up on the principle that “it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish” (John 11:50).

Péguy rightly saw in the analogy a sacred cause. The short-term success and long-term failure of the anti-Dreyfusards to win out against the facts would have great, even longer-term consequences. Péguy had enthusiastically taken up the Dreyfusard cause and did so out of his deepest nationalist and Catholic convictions, but by the turn of the century, he saw where its momentum was carrying French politics. The broad political left in France, under the influence of Jean Jaurès and, later, Émile Combes, had harnessed Dreyfusard energies to move the Republic toward the formal separation of Church and State and a series of anti-Clerical measures, culminating in the Combes laws of 1905.

Péguy’s “Memories of Youth” had therefore a very local occasion. With many other Dreyfusards, he was a socialist, a proponent of the Republic, and an opponent of anti-Semitism. But his socialism did not derive from Marxist, or what we would call neo-liberal globalist, convictions; it was not anti-national, but nationalist indeed. It was internationalist, he argued, only in the sense that he believed in the good of the nation and of other nations. He wanted to restore “the whole city to health”; “our socialism was a religion of temporal salvation.” Socialism, for Péguy, was a politics driven by a love of the nation, and not a new regime to supplant the nation.

If socialism was a religion of temporal salvation, it was not, he insisted, a secular cult intended to replace genuine Christianity. His Dreyfusard convictions sprang specifically from his Christian vision that Christ had sacrificed himself in our stead and so, to sacrifice another, was to cancel out the heroism of the cross. But, alas, the Church in France had become too bourgeois, had become “the religion of the rich”; it had closed itself off from the factory, and so the factory had shut her doors to Her. Christianity must be restored as “a religion of the heart,” and Christendom must be governed not by the intellectualism even then coming into its own in the Scholastic revival, but by a restoration of “charity.”

The right, particularly Action Française, had coined the term “intellectual” as a slur against the political rationalism of its opponents. But Péguy was convinced that he represented the politics of love—love of nation, love of the whole city, and love of Church and Christ—and did so in the name of those Catholics who often opposed him.

Apologia for the Fall

How did Péguy’s profound Catholicism of the heart wind up within a decade, issuing in the secularism and anti-clericalism of the Combes laws—laws which set the Church and the Republic at enmity, which expropriated the Church, and sent many religious into exile abroad? How had Péguy the Christian become a de facto enemy of the Church, the progenitor of a new secular order?

In answering that question, “Memories” makes its richest, almost its only, theoretical claim. Every true civic love is a mystique, a term we may define in a number of ways. A mystique is a general disposition of pietas to any fundamental principle, Catholicism, republicanism, monarchism, and so on. It is an ethos, a whole sensibility, a way of seeing the world, ordered by devotion to a principle whose final test is that one would willingly die for its sake. Christianity, as a religion, is a mystique, but not all mystiques are religions proper; they do, however, make claims upon our loyalties the way religions do.

The mystique of the Dreyfusards had been noble, coherent, formidable, patriotic, and courageous. As such, it could tolerate engagement with its opponents equally committed to their own mystique. But every mystique calcifies, hardens over time to a politique. Every mystique may well indeed entail a politique insofar as every strong set of principles will imply a program to follow from them (although, as an anarchist, Péguy left this last point in doubt). But a politique is not just policy, but the degradation of mystique to merely practical policy and the further corruption of policy to power. Once this occurs, mutual reverence and respect is impossible. There is only the winning of power by the taking of it from one’s enemy. This is what had gone wrong with the Dreyfusards of France.

There’s a touch of the nostalgic in Péguy’s theory to be sure, that temptation of the early leader of a movement to lament, but also excuse, the way things turn out as a consequence of a mere waning of spirit or ideals. In our day, it reminds one of the various books decrying the failure of conservatism; in both cases, we are belatedly instructed, the movement goes wrong just at the moment its ideals actually almost accomplish something practical—a rather doubtful lesson for the enterprise of political life, which is of necessity the art of the possible.

Further, Péguy’s insistence in “Memories” that it is the failure of charity in the Church, rather than the arguments of contemporary atheists or the intellectual defections of the theological modernists, that were undermining the faith seems to get something right and something wrong. The Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, as a young man, was a friend of Péguy’s and embraced his spiritualized politics, but he never considered himself a disciple. This was, in part, because Maritain saw well—as all disciples of St. Thomas must—that the will is seated within the intellect, and so to scorn the reason for the sake of embracing the heart more ardently is folly indeed and misunderstands human nature. Caritas is a condition of the “supernatural contemplation” to which all persons, by their intellectual natures, are called, not a substitute for it. Péguy made the Church to seem far more “bourgeois” and wanting in charity than it really was in his effort to explain why his nationalist form of socialism was a necessary temporal salvation placed at the service of eternal salvation.

But, on the whole, this risks unfairness to Péguy the man and overlooks the definite insight gained by his theory of civic mystique. The asymmetry between spirit and letter is true of all things, not just religion. Human social life consists primarily of shared devotions and only secondarily of procedures and policies. When love withers to mere program, decadence and corruption ensues.

Moreover, a mystique is a pietas toward our principles, a love that gives organic form, gives wholeness and shape, to a way of life. And yet, from Plato to Marx, our best political philosophers have taught us that a love of the Good is the narrow path through a strait gate, to either side of which lies the temptation of a mere pursuit of power, indifferent to goodness except as one more ploy to advance one’s personal interests. In brief, mystique is, among other things, a helpful term for describing the great political vision expressed by Saint Augustine, long ago, that the earthly city is created and ordered by whatever it most loves.

The Love of Cities

Only in “Clio I” does Péguy give us a full theory of the mystique and thereby make a compelling, if somewhat troubling, addition to our understanding of the nature of the political. In Péguy’s day, to affirm that his socialism was no deracinated, cosmopolitan ideology but a national socialism may have silenced some of his critics on the right; but, since World War II, such terminology can hardly be said to help his cause. The first serious encounter I ever had with Péguy’s writings, many years ago, was in a monograph by David Carroll that held Péguy to be a forefather of modern French fascism.

Carroll leaves one with the impression of Péguy as a dangerous naïf, who utters obliviously that France is eternal and so inadvertently become responsible for later horrors. In fact, Péguy’s Clio, muse of history and authorial voice of the essay (or most of it), has something rather astute to teach us. History is the stuff of time, it passes, and it must or it would not be history; but Clio, history herself as it were, is immortal, beyond time, and everlasting. History is eternity’s entrance into time.

Clio tells us that the ancients were right to celebrate the founding of a city with a feast, for to found something is itself a “religious action.” It marks a moment of creation, where there was nothing but now is something, an existent and bounded form—a city. In any “genuine” act of “foundation,” man creates something and it enters into the “temporal kingdom of [Clio’s] dominion.” It takes its place as a living being in the world that is at once organically one with, and yet transcendent of, its parts; the city is of and in time, and yet there is “something eternal” about it as well. In a word, to found or create is to bring the eternal into time and to give it being there so that we are living within and through the divine, each moment a revelation of something beyond time. Péguy’s favorite image for all this is the pater familias, the one who risks himself to bring something greater than himself into being, and who suffers to help it to flourish.

Christianity is often said to have relativized the cosmos, to have disenchanted it insofar as we see things as good, but as merely created goods, brought into being by the hand of God (as Joseph Ratzinger contends in In the Beginning, for instance). But, Péguy argues that the earthly city, that the world as a whole, must always retain a certain enchantment, a mystique proper to itself. Indeed, Christianity, recognizing the eternal element in the temporal city, did not abandon its reverence of the “civic.” To the contrary, “You Christians, the most civic of men, who are commonly said not to be civic, but who are if anything too much so,” transferred the temporal city to the very plane of eternity. The prototype and fulfillment of every temporal city lies in the civitas dei. Conversely, the pietas we rightly have for the City of God may and indeed should rightly coexist with a piety for the city that exists within history.

Péguy continues, Christianity is moreover the historical religion par excellence. God might almost be said to have created the world “badly” and to have done so on purpose, so that we would experience the temporal drama of salvation as giving to every moment and event of historical time a genuinely eternal significance. The pagan pietas for the earthly city, with its divine and eternal core, is not overturned but rather fulfilled through the entrance of God into the drama of history and the super-elevation of the city, in the Church, to the eternal. Péguy boldly asserts what it would take Henri de Lubac, decades later in his Catholicism, to make clear: the salvation of Christianity is corporate, achieved through the communion, the incorporation, of the faithful as members of the mystical Body of Christ. Our pietas to God and to his City are not competing loves, but one love.

From this perspective, the secularization or de-Christianization of the modern world is revealed not as a return to pagan superstition, a reassertion of strong, but immanent and pluralized gods, after the breakdown of Christian monotheism, but as the simple loss of the capacity to see history as a meaningful, organic whole. The world has not fallen into sin; no, says Péguy: “that would be nothing.” Christianity perceives the world as a contest between sanctity and sin. A world could still be Christian and sinful; but the modern age has abandoned sin and sanctity alike. It no longer sees history’s origins in eternity and “the eternal aspect of the temporal.” Modernity views all things with a debased materialism. Its cities may have been “instituted” but cannot be founded; they carry on well enough, but they are not joined in a common life. Modern society has renounced “the whole mystique.”

Mystique and Christian Humanism

It will help to understand the distinctiveness of Péguy’s theory if we contrast it with his near contemporaries. Péguy was an early exponent of the 20th century’s peculiar version of Christian humanism (which is the subject of Alan Jacobs’ important recent book, The Year of Our Lord 1943). A classic account of political life in the Christian humanist tradition is found in T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral. There, Eliot’s Bishop Thomas Becket affirms the supremacy of the eternal order of God to that of the temporal order of creation and human society. History, left to itself, is circular and endless to the point of being meaningless and nauseous. Only when the divine order pierces the otherwise closed circle do we discover that this circle of time is part of an intended, eternal pattern shaped by the hand of God and meant to lead us beyond time to our destiny and our salvation.

The political order is legitimate of itself, but of merely temporal significance. When Becket is tempted by the barons of England, whom Eliot models on the Nazis and fascists and other nationalist movements of his day, his response is categorical; the political has its place, but the Church is where all meaning and purpose is situated. All things temporal are empty except insofar as they come to signify in the light of the Church. Becket sends the barons packing with instant contempt.

Eliot later speculated that the age of the nation state was of recent vintage and its system was unlikely long to continue. There is little in the vast space between the self and God for the soul to love.

Péguy offers an alternative. Christianity envisions the true, eternal city, and a Christian society will be one ordered to it. That is the true mystique. But, because eternity enters time with every founding, because every temporal creation takes its place among the eternal realities henceforth, we may envision our lives as consisting of devotion, of pietas, to a great hierarchy of cities, from the heavenly to the earthly. Nothing will be forsaken, but rather everything redeemed, through the historical action of Christianity. Péguy will elsewhere argue for the universal salvation of all persons—because, I think, of his conviction that every temporal thing has a certain permanence proper to itself.

Eliot and Péguy agree that a de-Christianized world would be a merely material one, void and without anything proper to it worthy of our love and sacrifice. Eliot believed that a reawakening of the mystique of the Church was all that was needed. Péguy, however, envisions a whole, organic system of devotions, some more temporal than others, but all necessary for the “health” of the city. Our love for God may be the sole absolute, but from it is suspended a chain of historical realities that play a role in our lives and merit our pietas.

Allow me to offer still another comparison. Jacques Maritain and his wife Raïssa, Christian humanists very much akin to Eliot, reflected extensively on the meaning of the life of their close friend Ernest Psichari. Psichari was the grandson of the atheist and positivist French writer, Ernest Renan. As Raïssa writes of Psichari, his life constituted a long pilgrimage from the unbelief of his ancestor to redemption in the Christian faith; he was the representative man of a whole generation of French converts.

In the years spent passing between the poles of unbelief and reception into the Church, Psichari served as an officer in the French military in North Africa and cultivated a mysticism of the army, about which he wrote in several books. For the Maritains, these books of military asceticism and contemplation mark merely a transition, as their friend journeys with difficulty from the secular to the divine; once he has at last been received into the Church, all his writings on the army were superannuated and left behind. Péguy, in contrast, cites Pischari on the first page of “Clio” as one who can bear witness to the ubiquity of mystiques, to the divine mystery of every founding and of eternity’s entrance into time. Nothing needs to be left behind en route, because the God of eternity is also the lord of history, and every moment of time takes its place in the great unfolding map of eternity. We may have multiple mysticisms, because multiple things in history have claims on our devotion.

The Rebirth of Mystique in Our Civic Life

Péguy is thus no necessary anticipation of modern nationalisms that make of the nation a local god to blot out the one, true, and universal, God. He anticipates, rather, the political thought of Pierre Manent (who, not incidentally, introduces this volume), the leading interpreter of the nation state as the Christian political form par excellence. Péguy and Manent both revere the French republican spirit, at its best, for finding a place for every devotion proper to the human spirit.

Further, Péguy’s theory of the mystique helps to explain the phenomena that have led R.R. Reno to publish his recent books, Resurrecting the Idea of a Christian Society and The Return of the Strong Gods. For, Péguy understood that human beings are by nature creatures of pietas, and require, above all, the true Church, but require also the founding of a number of historical cities or institutions to which they can bind themselves in faithfulness and love. No dimension of our lives should be reduced to the provisional or the useful, to mere politique; the richest lives will be those that recognize an order of love, or loves, that in turn gives order to our lives. Nature hates a vacuum, and if modern civic life does not fill itself with a range of sound mystiques others, more dark, will make an entrance. That is the tale of the last century and may yet prove the story of the present one.

The great contemporary theorist of nationalism, Benedict Anderson, once opined that nationalism has been a force of great imaginative power, but one mostly lacking in theoretical insight by its exponents. Péguy himself was a theorist only in the sense of being a visionary, one who saw and contemplated what others had missed. The more systematic minds who now address the vacuity and desires to be found in our present politics confirm the essential insight that Péguy first mysteriously defined for the world as mystique. We require even now his passionate rhetoric to understand how crippling and dangerous it is for civic life to be reduced to a politique and also to catch a glimpse of how our familial, temporal, and eternal commitments must remain in closer and more permanent relation than even the other great voices of the Christian humanist tradition have recognized.