Islam, Blasphemy, and the East-West Divide

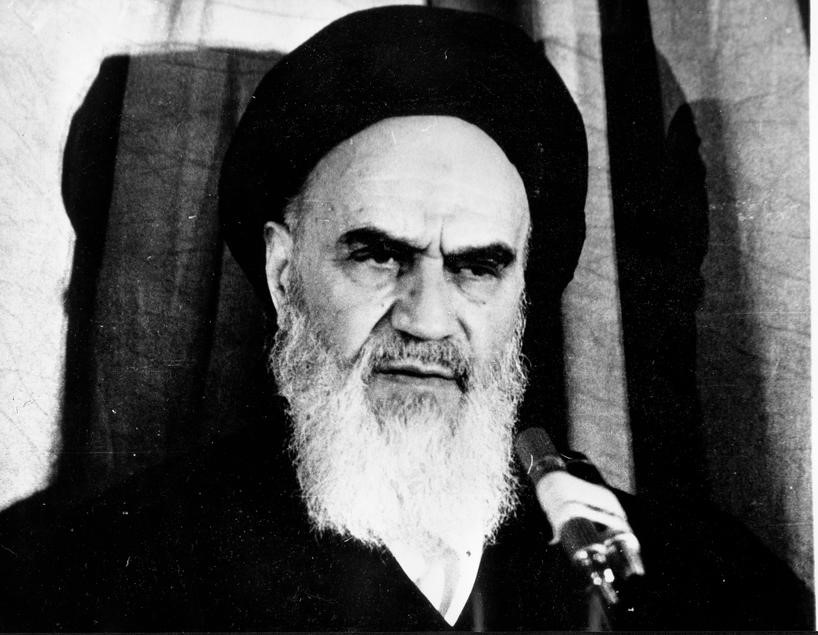

On a February morning three decades ago, millions of Westerners woke up to read in the news about an unfamiliar concept: a “death fatwa” by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, leader of the Iranian Revolution and the founder of the Islamic Republic, against British author Salman Rushdie. The reports sent shockwaves throughout the West and made the term fatwa, which in Arabic merely means “legal opinion,” the chilling word that it is for many today.

Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, published a few months before in the United Kingdom, had angered Muslims around the world. But no reaction had yet been as radical as that of Khomeini, whose verdict, as announced on Tehran radio on February 14, 1989, read:

In the name of Him, the Highest. Them is only one God, to whom we shall all return.

I inform all zealous Muslims of the world that the author of the book entitled The Satanic Verses—which has been compiled, printed, and published in opposition to Islam, the Prophet, and the Qur’an—and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its content, are sentenced to death.

I call on all zealous Muslims to execute them quickly, wherever they may be found. so that no one else will dare to insult the Muslim sanctities. God willing, whoever is killed on this path is a martyr.

In addition, anyone who has access to the author of this book, but does not possess the power to execute him, should report him to the people so that he may be punished for his actions.

May peace and the mercy of God and His blessings be with you.[1]

To make the call more appealing, the Iranian Relief Agency also announced a bounty of a million dollars to a non-Iranian assassin, and 200 million Iran riyals (equaling $170,000) to an Iranian one. Rushdie, who heard the news first from the BBC World Service, soon went into hiding under the protection of the British police. He would spend the next decade and more under police protection and in secrecy.

Khomeini embraced this cause as an opportunity to make himself into the premier defender of the faith in the eyes of the world’s over one billion Muslims. It was for the glory of the Iranian Revolution, a movement that he had spearheaded a decade earlier, which he envisioned as a model to be exported to other Muslim nations. This was a dream that had, in the years since the 1979 ouster of the shah of Iran, remained largely unfulfilled—not least due to the sectarian divide between the Shia Muslims of Iran and the world’s far more numerous Sunni Muslims. Khomeini’s Iran was, as it still is, also in competition with another Muslim power, Saudi Arabia, which was passionate to export its own brand of Islam called Wahhabism (a pietistic and literalist form of Sunni Islam).

Some commentators ascribe to Khomeini more mundane motives for the fatwa as well, mainly connected with his need to shore up political support among Iranians. The government had just concluded a humiliating armistice with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq after eight devastating years of the Iran-Iraq war. Then, too, there were the embarrassing revelations of dealings with Washington in the Iran-Contra affair.

In any case, the Ayatollah Khomeini would not have been able to issue a death fatwa if such a harsh response to blasphemy had no precedent in Islam—and if The Satanic Verses did not really look blasphemous in Muslim eyes.

Mahound and Jahilliyah

Rushdie was born in 1947 to a Muslim family in India, was educated in Bombay and in Warwickshire, England, and went into advertising in London after reading history at Cambridge. He described himself as a “secular human being” who did not believe in “supernatural entities.”[2] His prizewinning 1981 novel, Midnight’s Children, made his reputation in literary circles. The Satanic Verses (1988), which would give him international fame and notoriety, was his fourth book.

It made use of magic realism to tell the story of two Indian expatriates in contemporary England. One of them, Farishta, experienced dream visions having to do with a flawed prophet named “Mahound”—a derogatory term for the Prophet Muhammad that was used in medieval Christian texts. Mahound was based in a city called “Jahilliyah,” which is how Muslims refer to pre-Islamic Arabia. Mahound claimed to have revelations from God, but these were actually tainted by the devil. And perhaps even more irreverently, the women who appeared in the novel as Mahound’s wives were also prostitutes working at a local brothel.

Literary critics found the book interesting, but Muslims found it all too offensive. Ali Mughram al-Ghamdi, a British Muslim leader of the time, called it “the most offensive, filthy and abusive book ever written by any hostile enemy of Islam.”[3]

Soon Muslim organizations mobilized to get the book banned by the British government, which, under the leadership of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, refused to invoke the country’s long-obsolete law on blasphemy. More angry reactions followed. Copies of The Satanic Verses were publicly burnt in cities around the United Kingdom, a ritual that was repeated in cities throughout the Muslim world, where mass rallies were held to protest the book’s publication. After which came the Ayatollah’s death fatwa.

Rushdie, who now lives in the United States, ultimately survived the threat. He stopped hiding in 1998, when President Mohammad Khatami, who led Iran between 1997 and 2005, declared that the fatwa would not be pursued. (But Khomeiniites would not give up. In 2005, the Revolutionary Guards, with the blessing of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Khomeini’s successor, declared that the fatwa remained valid. In 2016, a hardline Iranian media organization raised the bounty on Rushdie’s head.)

Meanwhile other acts of violence related to The Satanic Verses did hurt other people. Before the fatwa, the anti-Rushdie disturbances in the United Kingdom and the Middle East produced few casualties. After the fatwa, more serious attacks came. Several bookshops in London were attacked with firebombs. The novel’s Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, was stabbed to death in July 1991 in Ibaraki, Japan. This was a few days after the novel’s Italian translator, Ettore Capriolo, was stabbed in Milan (he survived). There was also an assassination attempt on the life of the publisher of the Norwegian edition of The Satanic Verses, William Nygaard; he was shot three times in October 1993 in Oslo, but survived.

More such incidents were to come. The Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa opened the way for violent retribution against those who would depict the Prophet Muhammad or publish works that subjected, or were perceived to subject, Islam to criticism. In 2005, the publication of a series of cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad by Jyllands-Posten, a Danish newspaper, provoked international protests and boycotts. In 2011 and then 2015, the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo was attacked for daring to print cartoons of Islam’s prophet. In the latter attack, which occurred in Paris, 12 people were killed by terrorists belonging to “Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.” Their motive, they claimed, was “revenge for the honor” of the Prophet Muhammad.

And this summer, the world only barely avoided yet another drama. The “Muhammad Cartoon Contest” announced by Geert Wilders, the far-Right and unabashedly anti-Muslim Dutch politician, was cancelled at the end of August due to death threats. The latter came especially from Pakistan, where Tehreek-e-Labbaik, a fiery Islamist party, organized mass rallies and its leader vowed to “bomb Holland” if his group were ever able to acquire nukes.

In short, the friction exposed by the Satanic Verses controversy still haunts the world and will likely do so, again and again, in the future: a friction between the West’s commitment to free speech and Muslims’ aversion to blasphemy.

It is a friction that begs to be addressed.

Blasphemy Real or Perceived

The friction here is not just about vigilantes wielding guns and knives against those who blaspheme, or are believed to have blasphemed, against Islam. It is also about anti-blasphemy laws that are implemented in some 30 Muslim-majority countries, and are often supported by mainstream Muslim authorities. (In total, there are some 50 countries in the world that outlaw blasphemy, according to a 2014 Pew Research Center report. One of them, Ireland, abolished the “medieval” ban on blasphemy with a referendum in October.)

The people who are targeted by such laws can be real blasphemers—people who openly desecrate Islam’s holy symbols, such as the Qur’an or the Prophet Muhammad. But more often they are people who have no intention of disrespecting Islam but whose unorthodox opinions or faiths are labelled blasphemous. Such is the case of the Ahmadis in Pakistan, an unorthodox Muslim sect whose members believe in a 19th century Muslim messiah, and who are liable to be jailed, or physically attacked, merely for declaring themselves Muslims.

In Pakistan, one of the most censorious countries on this score, laws can also be cynically used to persecute non-Muslims over personal conflicts or differences of opinion. Such was the case of Asia Bibi, a Christian woman who had a dispute in 2010 with her Muslim coworkers on a farm over whether she had the right to drink from the same cup. The coworkers accused her of “insulting Prophet Muhammad,” and she had to spend the next eight years in jail. In October, she was pardoned and set free by Pakistan’s Constitutional Court, whose prudent decision that saved Ms. Bibi noted the Prophet Muhammad’s tolerance of Christians. Pakistan’s militant Islamists were enraged by the recent upholding of her acquittal, and continue to threaten her life. As this AP report points out, radicals shot and killed a provincial governor who publicly called the case a travesty, and a Pakistani government minister who challenged the blasphemy law met the same fate.

Identity Politics

Why is the Muslim-majority part of the world so averse to blasphemy—why does it, in the words of a 2017 story in Foreign Policy, have a “blasphemy problem”? The answers to this question are complex, with some stemming directly from religion, others only indirectly so.

Let’s begin with the latter. Quite a few Muslims in the modern world feel somehow alienated, humiliated, or persecuted by outside powers—not always but often Western powers—and the result is an anxiety that breeds reactivity. In other words, we are not talking about religious belief per se but an insecure identity that yields a reactionary political psychology. Blasphemous, even critical, treatment of Islam, in this view, is received as yet another assault against the oppressed peoples of the world that must be countered with fury.

One who witnessed the Satanic Verses crisis in the UK, the Indian-born British writer Kenan Malik, captured this secular motive in a recent article in the Guardian newspaper. “The Rushdie affair,” writes Malik, “was an early expression of what we now call ‘identity politics.’” As he observes,

Many anti-Rushdie campaigners were not religious, let alone ‘fundamentalist,’ but young, leftwing activists. Some had been my friends and some friendships foundered as we took opposite sides in the controversy. They were drawn to the anti-Rushdie campaign partly because of disenchantment with the left and its failure to take racism seriously, and partly because the left itself was abandoning its attachment to universalist values in favour of identity politics, easing the path of many young, secular Asians towards an alternative worldview.

In Islam other prophets, such as Abraham, Moses, or Jesus, are as sacred as the Prophet Muhammad; and God is more sacred than they. This leads to the conclusion (which I have drawn elsewhere) that the Muslim obsession with punishing insults, real or perceived, only about the Prophet Muhammad is a sign that identity politics is in play. Islamist militants are motivated by the treatment of Muhammad more than anything else. The source of the zeal is not just respect for that which is sacred, but a militancy to defend that which only the community or ummah holds sacred.

In other words, what we are seeing is connected to religious nationalism, which is distinct from religion itself. That may explain why, as Malik tells us, “many anti-Rushdie campaigners were not religious.” That may also explain why Pakistan is often the leading country in zealotry to police blasphemy—for in Pakistan, a nation founded on Muslim identity, nationalist fervor and religious fervor easily merge to become one.

East Versus West

Another aspect of the problem is a gap that exists, not between the West and Islam, but between the West and the East. In most Eastern cultures, honor and shame are determinative. One’s honor is fiercely defended, and putting shame on top of honor leads to even greater fierceness. Note that the Eastern cultures in question might include Eastern Christians as well, showing how cultural attitudes can cut across religious boundaries.

An observation that may help explain this phenomenon comes from Matthew Anderson, a doctoral fellow in the Department of Theological and Religious Studies at Georgetown University, who has studied blasphemy laws in Islam. In 2015, he went to Egypt to investigate an incident at the village of Kafr Darwish, where a Coptic Christian man named Ayman Youssef Tawfiq allegedly posted offensive material related to the Prophet Muhammad on his Facebook account. The perceived provocation led to violence against Coptic homes, which in turn led to a temporary exodus of the Coptic community from the village.

The incident sparked a national outcry. At its core there lay the belief that blasphemy is a crime—and it was shared by all. “Unexpectedly,” Anderson wrote, “I found that at least some Copts also believe that blasphemy, whether against Islam or Christianity, is a crime punishable by law.” He added:

Two Coptic priests we interviewed were explicit that it was indeed a crime if Ayman had actually posted offensive material on Facebook against the Prophet Muhammad. This will perhaps come as a surprise to those under the impression that all Christians in Egypt hold views on free expression or religious freedom that are identical to those of modern American liberalism.

Anderson also discovered, among the Muslims he interviewed, “a common insistence that there is a significant difference between what they considered to be formal criticism of the Islamic religion and speech or imagery (e.g. cartoons) intended to ridicule their faith. The former many deemed permissible, while the latter was to be treated as a crime.” This too seems to reflect a cultural gap: In the West, satire might be seen as a form of criticism; in the East, it can be seen as not mere criticism but insult—and there is broad consensus that insult is a serious crime which deserves serious punishment.

Roots within Religion

Aside from this intolerance’s cultural roots, it clearly has religious roots as well—which, of course, may be seen as either a reflection, or a sustainer, of the cultural roots.

Islam, unlike Christianity, is a legalistic religion with a body of law covering many aspects of life. It is called Sharia, which implies a divinely ordained “path,” whereas its human interpretation is called fiqh, or jurisprudence. The latter passes a verdict on blasphemy and it is not a light one. In all five major schools of Islamic jurisprudence—the Sunni Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi, and Hanbali schools, along with the Shia Jafari school—blasphemy against God or prophet (sabb Allah or sabb al-Rasul) is a capital crime. The only dispute is about whether the blasphemer ought to be saved from execution if he or she repents. Hanafis, Shafis, and Jafaris pardon the blasphemers who repent; the others don’t.

Needless to say, for a conversation about the compatibility of Islam and free speech to even begin, such verdicts in Islamic jurisprudence have to be reformed.

And arguments for reform have been mounted, going back at least to the 19th century. That was a time when Muslim scholars positively influenced by Western liberalism—such as Ahmad Khan, Muhammad Abduh, Rashid Rida, and Muhammad Iqbal—began to question some of the long-honored injunctions in the Sharia that conflicted with free speech, freedom of religion, or equality before law. The reformist perspectives they initiated have been passed down to new generations, including current scholars such as Rashid al-Ghannushi, Mohammad Hashim Kamali, Abdullahi An-Naim, and Abdullah Saeed.

The reformist argument has a two key components. The first and the most important is to go back to the most fundamental source of Islam, the Qur’an. Much of what later became established as Islamic law is absent from the Qur’an, and that is true for earthly punishments for blasphemy (or apostasy) as well. The Qur’an, on the contrary, has verses that command peaceful responses to blasphemy such as refusing to “sit together” with those who “ridicule [God’s] revelations” (as, again, I have explained elsewhere).

The second component of reform is to revisit the Sunna—the tradition of the Prophet Muhammad that is written down in “hadith” collections, or sayings, that were canonized almost two centuries after the Prophet’s death in 632 AD. These hadith collections, on which much of the Sharia is based, do include stories of the Prophet Muhammad’s ordering the execution of some blasphemers during the formative years of Islam. In particular, the story of Ka’b ibn al-Ashraf, a Jewish poet in Medina, whose execution by Muslims is narrated in the most authoritative hadith collection, has been taken by jurists as a precedent to execute blasphemers.

The reformist argument here is to reason that Ka’b ibn al-Ashraf was not killed for insulting the Prophet or Islam, but rather for “inciting people to go to war [against Muslims],” as Ismail Royer notes in an important article that criticizes Pakistan’s blasphemy laws from an Islamic perspective. Royer refers to traditional Hanafi scholars who had a more liberal take on the matter, including the 15th century jurist Badr al-Din al-Ayni, who insisted that Ka’b and a few other like him “were not killed merely for their insults [of the Prophet], but rather it was surely because they aided [the enemy] against him, and joined with those who fought wars against him.”

There is another kind of reformist argument as well, which is called “historicism.” It suggests that whatever one may find in the Qur’an or the prophetic tradition in terms of jurisprudence constitutes a body of historical facts that are bounded by their context, and are not necessarily normative for all Muslims at all times. The fact that the Qur’an legislates slavery, for example, doesn’t mean that slavery is a justified institution. One of the pioneers of this “historicist” reading of the Qur’an and the broader Islamic tradition was the Pakistani-born scholar Fazlur Rahman Malik (1919-1988), who spent his later life in the United States, teaching at the University of Chicago. Today there are “Fazlur Rahmanist” theologians in Turkey, Indonesia, and elsewhere who are trying to advance his approach.

The Way Forward for Islam

Such reformist arguments can be heard all over the Muslim world—along with the conservative reactions to them. Comparatively speaking, the Muslim world, on average, is at the very same period when John Locke wrote A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) or John Stuart Mill wrote On Liberty (1859). There are liberals pushing for change, in other words, against conservatives who think the heretics and the infidels must be punished and all subversive ideas must be banned.

There is no straight path along which this reform may proceed, given that Islam, unlike Catholicism, has no central authority that can change the religious doctrine of its 1.5 billion followers. In this sense it is more like Protestantism, where authority is diffused into countless numbers of national institutions, traditional centers of learning, charismatic leaders, televangelists, modern theologians, moderates, radicals, and many perplexed individuals.

Progress—towards liberalism—may take place only as more and more Muslims find reformist arguments convincing. And that can take place only as more and more Muslims feel themselves at home in the modern world, rather than being “otherized” by that world—let alone being threatened, invaded, or bombed by it.

On blasphemy, in particular, Muslims will come to accept liberal norms when they understand that they are not helping their religion by meeting criticism, or even mockery, with violence and fury. They are only proving to be immature, and are only provoking more insults against the faith.

This may be hard to understand for the militant Islamists in the slums of Pakistan, but Muslims living in the West seem to be finally getting how things work here. This was evident in the remarkably mild stance that Dutch Muslims took when Wilders tried to organize his “Muhammad Cartoon Contest” in Holland. Anger waxed in Pakistan, but not in the streets of Dutch cities or towns, as the Guardian reported. “It’s easy to spread hate,” said one Dutch Muslim, Usman Firdausi, “but the best response is dignity.”

Dignity, indeed, is the right response to the Muhammad cartoons or The Satanic Verses. And 30 years after the Ayatollah’s death fatwa, not all Muslims but at least some Muslims seem to be getting this right.

[1] Daniel Pipes, The Rushdie Affair: The Novel, The Ayatollah, and the West (Birch Lane Press, 1990) p. 27.

[2] “Fact, Faith and Fiction,” Far Eastern Economic Review, March 2, 1989.

[3] Leonard Williams Levy, Blasphemy: Verbal Offense Against the Sacred, from Moses to Salman Rushdie (UNC Press Books, 1995), p. 562.