The historical-practice standard established by last year's landmark gun-rights case is proving to be manipulable in the lower courts.

Prohibition and the Constitution's Limits

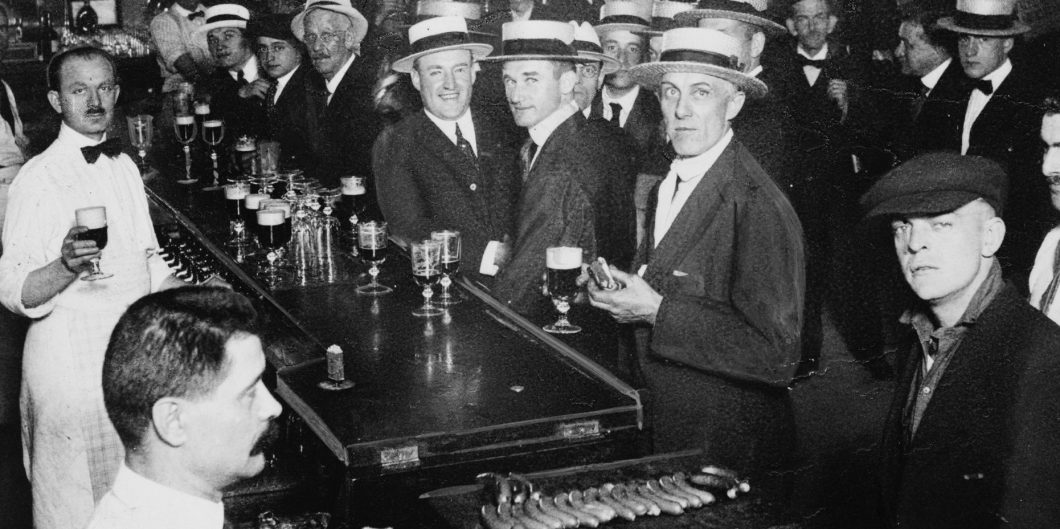

As Richard Gamble aptly observes, Prohibition offered an unholy fusion of a muscular Christianity and militarized patriotism, but it did not stop there. It was also favored by a long list of groups that is, if not quite exhaustive, is still exhausting in length: progressives looking to use government (especially federal) power to build a better society, social reformers looking to alleviate urban poverty, anti-immigrant nativists, immigrant advocates looking to cultivate moral uplift, business interests seeking a more reliable workforce in an age of ever more dangerous machinery, Southerners hoping to shore up white supremacy, black leaders hoping to revivify enforcement of the Reconstruction Amendments, anti-corruption reformers looking to excise machine politics (so often organized around the saloon) …. and so on.

With such an overdetermined coalition behind it, it is not hard to see why self-righteous prohibitionists could end up with the zeal Gamble so aptly criticizes, a zeal so strong that some of its members would literally add poisons to industrial alcohol, reasoning that a few blind scofflaws would prove a useful ingredient in testing the Noble Experiment. Prohibition’s list of sins—its contempt for states’ rights, the rise in violent crime, the growth of a bureaucratized and militarized federal law enforcement necessary to combat said crime, and the elitism of rich scofflaws imposing a policy on the masses that their affluence allowed them to buy their way out of—proved obviously far greater than its benefits in reducing America’s overconsumption of alcohol.

Nonetheless, I would like to offer at least one reason why, if not a net good for the country, Prohibition had some underappreciated positive contributions that would be of particular interest to readers of Law & Liberty.

The Eighteenth Amendment itself may have been a black mark on the Constitution, but it nonetheless manifested as part of an extended debate that was, with remarkably few exceptions, a high point for American constitutionalism. At least until the very end, when desperation for Depression-era revenue caused economic arguments to come to the forefront, prohibition was fought almost entirely within the discourse of constitutionalism—of the rights of states versus national power, the exclusivity of Article V amendments, and constitutional oaths and obligations. Political figures were perfectly willing to call out popular contempt for constitutionalism—and even, almost incomprehensibly to us in an era where re-election in a winner-take-all age of polarization trumps all—to take their oaths seriously enough so as to give up political careers for them.

Constitutional Scruples

In World War I Britain, David Lloyd George, on the cusp of becoming Prime Minister, proclaimed that the country did battle “against Germany, Austria, and drink and, as far as I can see, the greatest of these deadly foes is drink.” But while Lloyd George had long been a prohibitionist, and thus was happy to use the Great War as a pretext to implement his already pre-existing views, his American counterpart as wartime head of government still had some sense of shame in considering prohibition.

As Gamble observes, a (perhaps uncharacteristic) moment of constitutional scruples led Woodrow Wilson (or at least his wife, acting as de facto president) to veto the Volstead Act on October 27, 1919. The grounds for the veto were pretty straightforward: before the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect in January 1920 (one year after its ratification), allowing the federal government to impose local prohibition, any such federal suppression of alcohol would depend on war-making powers. But with the conflict in Europe having arguably concluded, it would be wartime prohibition without a war—and thus unsupported by any enumerated federal authority and consequently without any legal sanction. Even for Wilson, who had spent most of his intellectual life deriding the Constitution’s structural divisions of power as obsolete, this was too much.

While one could certainly dispute, as Wilson did, Congress’s contention that the war was still ongoing with demobilization still technically in process (and no treaty signed), on the whole, prohibitionists were surprisingly conscientious of and attentive to constitutional arguments. It was, to paraphrase Gamble’s ominous but apt conclusion, a politics chastened by (legal) history.

In what is perhaps an obvious point to make, but in light of the subsequent decay of constitutional seriousness that characterizes our politics today, is one still worth making: the prohibitionists did not simply attempt to capture the Court and force through a tortured constitutional interpretation to justify what they wanted to do.

Instead, as they often reminded critics who lamented the Eighteenth Amendment as a blot on the Constitution, in tension with its clear spirit of federalism, it was an amendment—a point in turn recognized by most of the opponents of national Prohibition. For example, in opposing the amendment in 1917, Henry Cabot Lodge (R-MA), the de facto Senate Majority Leader, noted that federalism was the cornerstone of the American Constitution and that morals legislation properly belonged to the states’ police powers—but the proposed amendment, while a bad idea and one he passionately sought to block, was legitimate and would be binding (albeit ineffectual in implementation).

The Anti-Saloon League and its allies had gone through the trouble of persuasion, mobilization, and lobbying to build sufficient political power to make that change. This not only gave democratic legitimacy to Prohibition as consistent with popular consent and sovereignty but subsequently gave prohibitionists the credibility to actually enforce it. When fickle politicians changed their mind, the Anti-Saloon League reminded them that all but three states had agreed to the change in the most solemn way possible (and most of those three northeastern states—New Jersey, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, to their credit, nonetheless become honest enforcers of the Amendment, which they recognized as binding, even as they sought its repeal.)

Moreover, prohibitionists argued, with some credibility, that they had actually strengthened federalism by doing all this; they had solidified the precedent that one could not simply torture the general welfare provision of the spending power, or an endlessly malleable causal chain attached to the commerce clause, to authorize federal power to control intra-state economic affairs. Instead, the prohibitionists had confirmed the exception that proved the rule—if you wanted to add to federal power, you needed to actually add to the limited enumerated powers of the federal government via a real, proposed, and ratified amendment. Such constitutional reasoning was subsequently ignored in the constitutional hand waving behind Wickard v. Filburn (1942), where a farmer growing wheat for his own use was ruled to have an effect on interstate commerce and to be in violation of production quotas established by federal law, or Gonzales v. Raich (2005), which rationalized the analogous federal suppression of intrastate marijuana. As Representative Franklin Mondell (R-WY) noted in explaining his support for the amendment with his otherwise narrow interpretation of federal power, “I have no criticism of those who in good faith strictly construe the powers of the Federal Government under the Constitution” partly because his “own inclination is that way.”

Thus, not only those proposing the amendment in Congress but subsequent defenders, like Senator William Borah (R-ID), arguably the most effective popular defender of prohibition, could be completely intellectually honest in reconciling their prohibitionism with otherwise passionate commitments to the federalism found in the Constitution’s text.

Note too, that while the prohibitionists argued that the unique text of the Eighteenth Amendment (specifically setting a policy and not merely a power) meant the states were legally (and morally) obligated to assist federal enforcementthey never assumed Congress could directly coerce the states or state officers to assist. Thus, while prohibitionists believed any state laws formally repealing state enforcement were unconstitutional as repugnant to the Eighteenth Amendment because the states were constitutionally obligated to help with the suppression of alcohol, Borah, the Anti-Saloon League, and their allies recognized that it was an effectively unenforceable obligation. In other words, even as the prohibitionists derided many states for refusing to implement a constitutional mandate, they still honored what we would subsequently call the non-commandeering doctrine. As a result, even the states’ rights-committed President Calvin Coolidge embarrassedly withdrew a proposed policy (almost certainly offered without his direct knowledge) which would have voluntarily deputized state law enforcement officers.

Reluctant Prohibitionism

I could, and in my recent book, do, discuss the constitutional scruples of many other figures, but three in particular stand out:

As then-Governor Coolidge observed in vetoing a bill that would have sought to legalize beer within Massachusetts,

My oath was not to take a chance on the Constitution. It was to support it…Opinions and instructions do not outmatch the Constitution. Against it, they are void…Instructions are not given unless carried out constitutionally. Instructions are not carried out unless constitutionally. There can be no constitutional instruction to do an unconstitutional act.

Stirring stuff for a constitutionalist, textualist, or originalist, as Coolidge insisted that his oath trumped the popular will and temporary democratic majorities. That Coolidge almost certainly opposed national prohibition (on both federalist and libertarian policy grounds) and nonetheless defended it counts for much; that it was also bad politics, in a ferociously wet Massachusetts, counts for more.

New York Governor Nathan Miller, who campaigned with Coolidge on grounds of constitutional fidelity, similarly insisted on wholly rejecting anything that smacked of nullification. Even though he detested national Prohibition as a betrayal of federalism, and made no secret of that either before or during his governorship, he insisted that New York had to assist its enforcement. This was both as a matter of constitutional duty and because state abdication would further destroy his cherished federalism by incentivizing the creation of national law enforcement machinery. In very, very wet New York, this functional prohibitionism—even if for very different reasons than the true believers—was political suicide, and Miller was trounced by Al Smith in the next election.

Wisconsin’s Fred Zimmerman is all but forgotten today, but worth remembering for his similarly heroic constitutionalism. Zimmerman was, like his mentor and predecessor John Blaine, a part of the state’s progressive Republican faction. Like Blaine, he insisted that the state had to help prohibition enforcement until the amendment’s repeal, and to that end he issued a widely re-published veto message decrying state legalization of alcohol as “an invitation to the citizens of Wisconsin to violate federal law,” recalling “the dark chapter of American history…. when [South Carolina] passed an act refusing to abide by a federal law.” For this, he likely lost his job the next time he faced the voters. Only after the election did it turn out that Zimmerman was like Blaine in another way: he despised the Eighteenth Amendment as a distortion of federalism and sought, as a private citizen, to have it repealed—but he simply would not abet its violation when under the oath of office under the Constitution.

As an aside—consistent with the unforgiving voters in those states—and against those who might see the losses of Miller and Zimmerman as popular contempt for constitutionalism, I tend to think that Miller, Zimmerman, and the others who shared that view were wrong. Those like Al Smith and Albert Ritchie (MD) arguing for state inactivity on national prohibition, on what we would effectively call non-commandeering grounds, had a marginally better case here. Nonetheless the claim that the unprecedented text of the Eighteenth Amendment imposed a unique affirmative duty on the states, overriding the non-commandeering doctrine (just as it overrode Tenth Amendment police powers within this sphere) is a plausible and very defensible one. But regardless of whether Miller, Zimmerman, and others were right in their constitutional claim, constitutionalists ought to admire them for being willing to pay a real price for constitutional fidelity.

In addition to those three, others who set their policy views aside for their constitutional duty included a who’s who of American political leaders in the 1920s. William Howard Taft aggressively campaigned against the amendment as both bad policy and a distortion of federalism—and yet, after its passage and his elevation to the Supreme Court, became one of its most faithful enforcers. Warren Harding, notoriously pliable on prohibition as a Senator, concluded that his (perfectly legal) cache of pre-Prohibition booze nonetheless served as an incitement to law-breaking so he moved to dispose of it shortly before his death. The loudly, obviously anti-prohibitionist Senator James Wadsworth (R-NY) still was among many in Congress who believed that he had to vote to prop up the Volstead Act until the amendment’s repeal. He would lose his Senate seat at the hands of a vindictive Anti-Saloon League happier to deploy a spoiler candidate who ensured there would an openly ultra-wet Democrat rather than an unreliable Republican. Al Smith, who engaged in an indirect constitutional debate with Warren Harding, repeatedly disavowed obstruction of federal law, and was clearly tortured by doubt as to whether his constitutional oath allowed him to disengage New York’s law enforcement regime. Finally, even as he admitted the inevitable and endorsed the modification or even repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment, Herbert Hoover promised to veto any repeal of the Volstead Act that preceded said repeal. The list goes on.

Of course, not everyone was so scrupulous. In a surprisingly underappreciated maneuver, the Anti-Saloon League and its allies managed to spike the constitutionally required reapportionment following the 1920 census; it simply didn’t happen, since raising the proportion of urban voters would weaken the dry congressional contingent.

But while Woodrow Wilson comes out surprisingly well in taking the Constitution seriously under prohibition, Franklin Roosevelt does not. Earlier in his political career, as an advisor to Al Smith, Franklin Roosevelt argued that Smith should cite his constitutional obligations in vetoing an effort to legalize alcohol in New York while discreetly defunding its enforcement to appease anti-prohibitionists. (Roosevelt’s call to concede a constitutional obligation while quietly undermining said constitutional oath appalled Smith.) In 1932, Roosevelt continued to position himself as a states’ rights defender in campaigning for the Democratic nomination, using his opposition to the Eighteenth Amendment as a key part of the case. This proved sufficient not only to muscle out his former mentor Smith but also Maryland’s Albert Ritchie, the leading states’ rights man in the country. Roosevelt’s professed fidelity to constitutional decentralization even managed to gain the support of the ardent federalists at the center of the repeal movement, the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment—who responded to Roosevelt’s betrayal of federalism on almost every other issue with buyer’s remorse. (They refounded themselves as the Liberty League.)

Prohibition obviously did much harm; this is not a lament for the 21st Amendment and its return to federalism, with which I am deeply sympathetic. Still, an era in which constitutional oaths were seriously invoked to the point of political suicide, in which Article V was valorized as the exclusive method of constitutional change, and in which the nuances of federalism were debated—with everyone vying to be a moderate states’ rightser faithful to the actual enumerated powers—deserves at least one cheer and maybe a now legal toast.