What nukes, aid, and blockade mean for the conflict over Taiwan.

Prohibition, Protestant Unity, and Progress

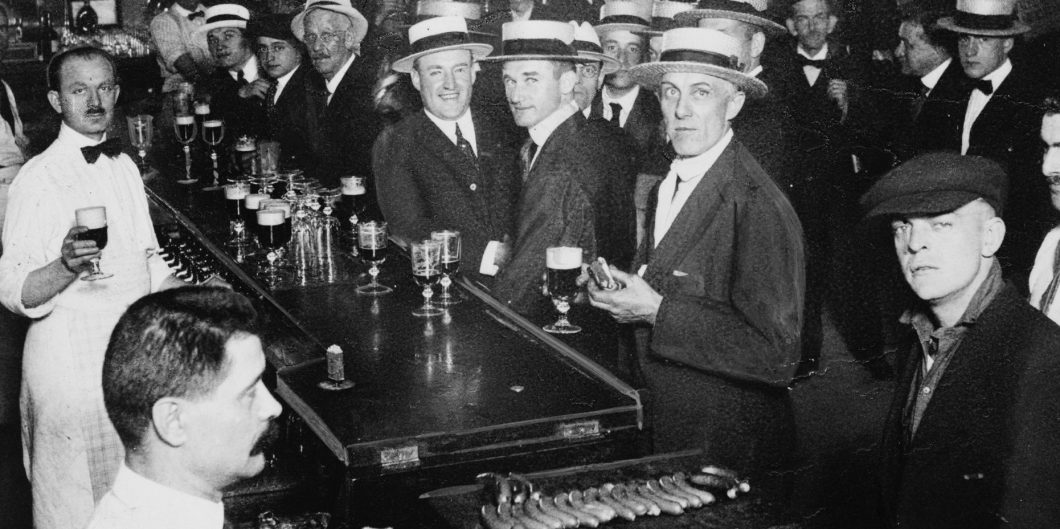

In the popular imagination, Prohibition is strewn with familiar imagery: speakeasies, bootleggers, police with axes, ready to pour dozens of barrels of whiskey down the drain, Al Capone’s mugshot or the ghastly aftermath of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Fortunately, Richard Gamble’s “‘Two Kaiser’s in the Same Grave’: 100 Years Since Prohibition” places this episode in American history in a broader context of a dual war on alcohol and Germany and demonstrates the larger significance of this fascinating time in our national past. For, as the author shows, Prohibition unified disparate elements in American society generally and American Protestantism specifically in an effort to make America and even the world dry and democratic.

What Gamble convincingly shows is that Prohibitionists waged war against more than just alcohol and the Kaiser; they fought against a changing America that included the New Immigrants, an influx of primarily Catholics from Eastern and Southern Europe, many of whom would not, for cultural reasons, support “dry” legislation and the viewpoint that sustained it. The moralizing reform of American Protestantism which has a long history in American life, combined with the motive of American Exceptionalism, convinced many it was their duty to spread their true democratic Christian faith to a humanity sorely in need of it.

Secular progressive reformers worked with a variety of (principally) Protestant Christians from numerous denominations, whose numbers included both theological liberals and conservative fundamentalists. Their efforts—rooted in the temperance movement originating a hundred years before—were crowned with success in the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act in 1919.

As Gamble has shown in his cogent essay, temperance reform had a long and checkered history in American life. Attempts to reform the “alcoholic republic” originated in the early antebellum years with the temperance movement gaining considerable strength in the twenty years prior to the Civil War. Teetotalers (so-called because of the symbol they wrote with a crossed ‘t’ indicating their support for “Total Abstinence” from alcohol of any kind) established organizations both secular and religious devoted to ridding America of the pestilence of strong drink which, they maintained, had sapped the moral fiber of American life and cost the republic dearly since the Founding.

As the author convincingly argues, temperance and, later, prohibition supporters were part of a much larger effort—a crusade—to make the world (or at least America) conform to their idealized standard of culture. They waged war against the autocratic Kaiser to make the world safe for democracy while simultaneously slaying the dragon of “demon rum” in all its forms. What is especially intriguing in Gamble’s discussion is the confluence of such a variety of monumental efforts whose adherents demanded an “all-or-nothing” approach to their respective, though interrelated, efforts. Much as teetotaling Prohibitionists demanded total abstinence and Wilson demanded total mobilization, so the Progressive reformers insisted upon the total supremacy of the community over the individual, or, as Columbia professor Frank Goodnow Johnson would have it, the triumph of “social expediency rather than individual right.”

Such absolute demands underscore the seemingly limitless hopes that many in the United States and beyond placed in the postwar world order. The specter of “100 percent Americanism” with its demands for social conformity engaged a broad cross-section of Americans both urban and rural. As Gamble rightly points out, this crusading spirit of postwar America culminated in a unified effort, seeking “universal solutions to men’s most vexing problems.” His list of problems—the two Kaisers—might be augmented by a number of others which impacted this crusade to greater or lesser degree. Factors such as nativism, Anglo-Saxonism, and Social Darwinsim all contributed to increased support for immigration restriction from the peoples of Europe and Asia held to be inferior for any number of reasons including race and religion. Thus the adherents of 100% Americanism might realize a homogeneous culture and society, Protestant and Anglo-Saxon—as well as dry and democratic.

The forces of a renewed nativism, so evident in the anti-Irish, anti-Catholic Know Nothing era of the 1850s, began to gather strength in post-Civil War America. The strident nationalism they espoused exhibited fears of rampant, unchecked immigration that would result in unwanted newcomers, most of them Catholics. Nativist sentiment included the conviction that the New Immigrants regularly imbibed both alcohol and political radicalism and must be stopped lest they corrupt the social and political order of America. Henry George, best known for his advocacy of the “single tax” on land, fretted over the influx of what he called “human garbage” from abroad who threatened by their very existence in America to introduce the very worst aspects of Europe into the country.

Frances Willard, who established the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in Ohio in 1874, wrote in 1850 that “Alien illiterates rule our cities today: the saloon is their palace; the toddy stick their scepter.” And Josiah Strong, Secretary of the Evangelical Alliance and author of the widely read work Our Country: Its Possible Future and its Present Crisis, in 1885, predicted continued greatness for America but only if it retained its Protestant, Anglo-Saxon moorings. Foreigners, he said, were responsible for most of the crime, the degraded morality, and the increased alcohol consumption so evident in urban, industrial America. Distinct voting blocs of Catholics (as well as Socialists and even Mormons) threatened, Strong maintained, to corrupt city politics beyond all hope of recovery. Like many nativists of his day, he believed recent immigrants often came from countries with no experience in democracy and thus they were easily coopted by urban political bosses who bought their votes and used them to maintain control of their crooked political machines. Catholics of the New Immigration, as newcomers, had a substantial role in the consumption and trafficking of liquor, retained their “peculiar customs,” and oftentimes settled in foreign-born enclaves where, unwilling or unable to “Americanize,” they constituted a threat to a nation increasingly in peril.

Progressive reformers who lamented the ill-effects of foreign immigration found allies in the Social Gospel movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Sydney Ahlstrom once noted that fellow historian “Paul A. Carter does not exaggerate in calling the dry cause ‘a surrogate for the Social Gospel.’” Leaders such as Washington Gladden, Richard Ely, and above all, Walter Rauschenbusch, sought to harness an activist Protestant Christianity to the cause of social and political reform. Jacob Riis, author of the 1890 work How the Other Half Lives, demonstrated the impoverished, often unsanitary conditions of the urban tenement. Though he undoubtedly sought to improve those conditions, Riis encouraged, if unintentionally, a renewed disdain for foreign immigration. Ely admonished his fellow Christians to engage in political and social action, for it was the true calling of Christ to the faithful and Ely downplayed more traditional practices of sermons and missionary evangelization in favor of social action. Rauschenbusch lamented the overemphasis on sin and conversion which, he maintained, limited the “religious imagination” of too many Christians: social work was the highest Christian motive and Christians should be more concerned about the plight of their fellow man and incarnating Christian beliefs in the community and less worried about their individual salvation. And as late as 1924, well-known Social Gospeler Reverend John Hayne Holmes debated the issue of prohibition with Clarence Darrow, maintaining that alcohol contributed mightily to the poverty and crime so prevalent among immigrants and which had come to typify so much of urban America.

These efforts suggest the real if temporary Church of America to which Gamble refers—an allied campaign of “enlightened” Christians lasting just long enough to see the victory won. It included social justice advocates such as Jane Addams who, in her “Subjective Necessity of Social Settlements” had warned about the enervating effects of moral and social complacency, but who also perceived a “renaissance” emerging in American Christianity by which she meant a return to a supposed primitive Christian church in which creed and clergy had no place, and where Christians fulfilled the dictates of a properly-formed Christian conscience and simply loved one another as Christ commanded, placing the good of the larger community above any selfish individual gain.

While the wartime hopes for a world made safe for democracy collapsed at Versailles, the goal of a dry republic was intact and on the verge of its greatest success. With the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act, America would soon be dry, at least in theory. Americanization, “100% Americanism,” had accomplished a major goal in its agenda to purify the republic. However, those who had hoped the New Immigrants would Americanize saw their efforts at cultural assimilation (or transformation) come to naught, and with that recognition came a return of a severely nationalist fervor and anti-immigrant outlook.

Nativists included seemingly disparate elements of American society: progressives and conservatives, urban and country dwellers—all united at the least by their determination to not allow foreigners to jeopardize their own understanding of the ideal society, whatever that might entail. A renascent Ku Klux Klan, for example, having added Catholics and Jews to blacks on their list of undesirables, enjoyed increasing support in the postwar era from a diverse geographic region. They engaged the support of increasing numbers of Midwestern and southern Americans in their campaign to rid the country of the lawlessness brought on by the renewed influx of foreign immigrants in the postwar period. The solidarity prohibitionists enjoyed was at least strong enough to divide the South politically in the 1928 election and prevent the Democrats’ nominee, the wet and decidedly urban Roman Catholic, Alfred E. Smith, from winning the presidency. Their victory, however, was more apparent than real.

Gamble speaks of the “unintended consequences” this war entailed and indeed there were many. Ironically, the very people the nativist, 100 percenters sought to Americanize and assimilate or, failing that, oppress and restrict, were oftentimes the very ones who benefited from the attempt, however futile, to enforce the war on alcohol. Religious and ethnic minorities—Jews, Poles, and Italians—all took advantage of the opportunities Prohibition and its attempted enforcement provided, whether in production, distribution or sales. That this moment of substantial (though by no means complete) Protestant unity in America—progressives, Christian Socialists, Social Gospelers, and Fundamentalists working toward a common goal—ended in failure is due, at least in part, to the determination to impose an uncompromising, conformist ideal that suggested a rigid, legalistic application of Calvinist orthodoxy—the triumph of the will incarnated in social action at the expense of the intellect and theological contemplation. Whether degenerating into a vague, humanitarian ideal, as with the Social Gospel or the most severe discipline of Calvinism, neither had the capacity to overcome the idealized vision of America each held dear.