Government interventions, in attempting to artificially allocate resources, actually help fuel inequality.

Jack Balkin

Recent

The television series Manhunt reassures viewers of American triumph without wrestling with its great conflicts.

The formal equality of opportunity that we already have is the only form of it that is not inherently tyrannical.

Counter-speech is a mechanism used by traditionally marginalized individuals to contest allegedly harmful speech.

Land acknowledgments amount to the hollow incantations of hollow people.

Masters of the Air gives viewers a glimpse of what American airmen experienced when flying strategic bombing missions in World War II.

A newsletter worth reading.

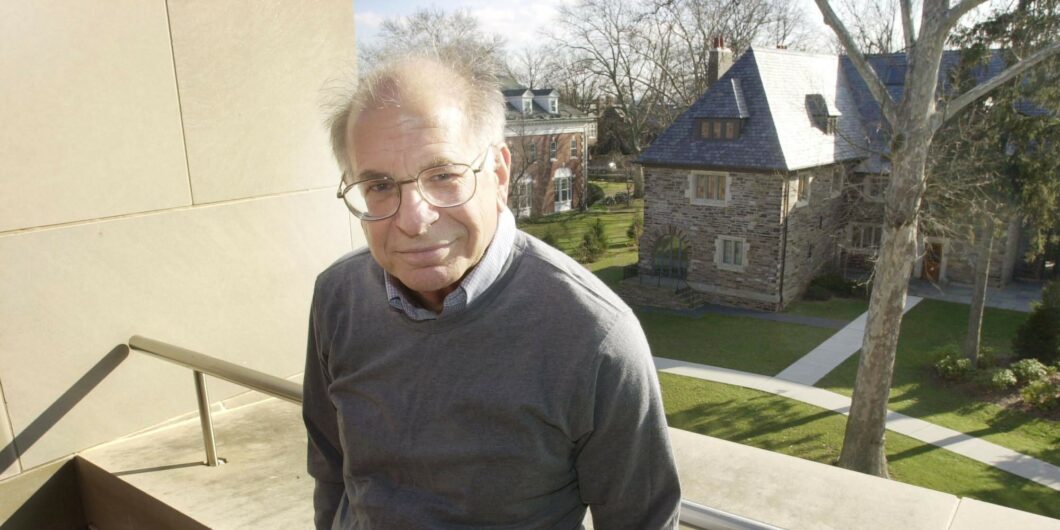

Daniel Kahneman, who passed away last month, had a profound impact on the way we understand human decision-making.

Despite its name, post-liberalism does not offer any genuinely new ideas.

We have built up all kinds of narratives about the struggle to lose weight, then along comes science and sweeps the difficulties aside.

The early church looked to civil authority to promote peace and security, enact just laws, and allow the free exercise of religion.

Like others before it, the tragedy of October 2023 will irrevocably alter Israel’s DNA.

Poor Things uses a woman born in a Victorian laboratory to explore humanity's relationship to science and technology.